Recognising First Nations Knowledge Systems

Thanks to the Blue Mountains World Heritage Institute’s recent newsletter, calling for us all to become Blue Mountains Guardians of this precious area of Australia, I found out about this important forum for reimagining conservation in Australia by bringing together First Nations scholars and knowledge holders with non-Indigenous scholars and activists in the area of nature conservation and environmental management.

Profound changes are afoot. As we think about the approaching summer and fire season, more and more attention has been given to First Nations systems of fire management (cool burning), a methodology they developed over millennia that shaped the Australian landscape. Indigenous scholars and environmental managers are leaning how to TALK back to ‘white’ knowledge holders. ‘White’ knowledge holders are losing some of their assumed intellectual arrogance, that Western science has all the answers. But we non-Indigenous folk have a long way to go for unconscious bias operates at many, many levels in how we see and act in the world.

The Reimagining Conservation Forum – Working Together for Healthy Country was a collaboration between the North Australian Indigenous Land and Sea Management Alliance (NAILSMA), Protected Areas Collaboration (PAC), Australian Committee for IUCN (ACIUCN) and NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service. This First Nations-led Forum brought together First Nations and non-Indigenous leaders and practitioners involved in the policies and practices of land and sea management across Australia.

The Forum, involving over 100 people was held in Brisbane over three days, November 2nd – 4th, 2022. Day 1 of the Forum was for a 30-person Focus Group of First Nations leaders in land and sea management, by invitation. A wider group representing a balance of First Nations and non-Indigenous people, participated on days 2 and 3 (November 3-4).

Below is a screen grab of the poster issued by the Forum, which outlines the six key themes that were adopted to shape future practice in land and sea management and conservation. Although weaving knowledge systems is identified as the 3rd theme, it actually underpins all the other themes.

- Recognising the rights of Indigenous people in Country – their social, cultural and economic needs

- Valuing culture and recognising Indigenous cultural authority

- Weaving knowledge systems

- Equity in managing Country

- Managing Country together

- Economic opportunities arising from renewable energy and native produce must be in harmony with Indigenous cultures and ensure benefit to local communities

However unless the differences in knowledge systems is acknowledged, and ways found to weave them together at an ontological level, as well as an epistemological level, it is the nature of the Western knowledge system for it to merely pay lip service to this principle.

However unless the differences in knowledge systems is acknowledged, and ways found to weave them together at an ontological level, as well as an epistemological level, it is the nature of the Western knowledge system for it to merely pay lip service to this principle.

The Western market-based nature of modern corporate institutions is ruthless in the pursuit of its extractivist logic. We see this playing out at the moment in the probe into malfeasance in the consulting sector, the mining sector, the housing crisis, growing wealth inequality, and wage theft in the gig economy.

As Indigenous individuals and community seek their share of economic opportunity, they will not be immune to the allure of this logic as we already see in the various spokesmen for the No campaign on the forthcoming Referendum for constitutional recognition with a Voice to parliament and government.

Underpinning the Forums’ reimagining of the future of nature conservation in Australia is the recognition of First Nations Knowledge systems (epistemology). However, to really weave our different knowledge systems together, we must go deeper into ontology, our fundamental assumptions and beliefs about the very nature of reality and how we relate to it, experientially.

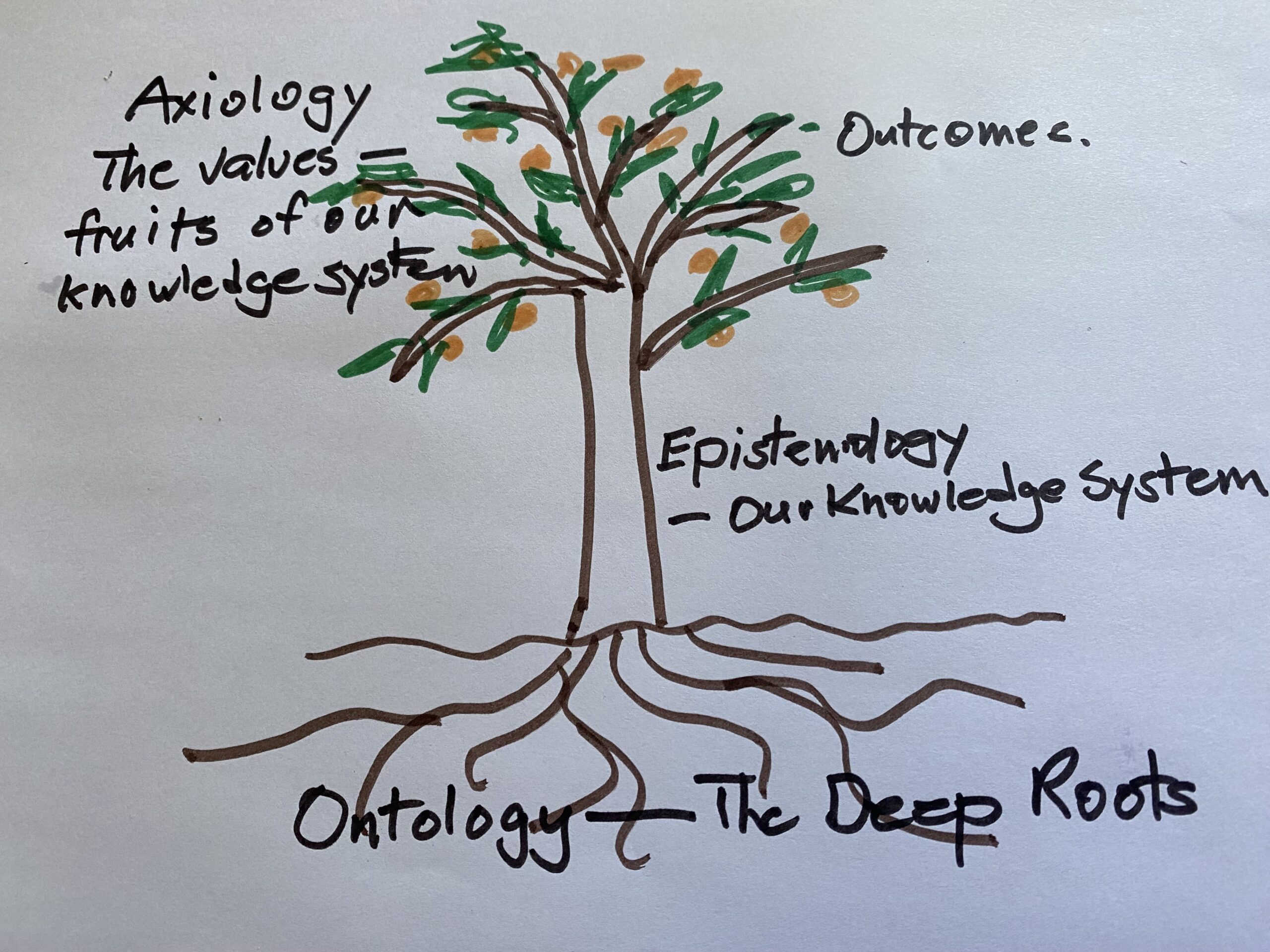

Metaphor of a Tree

- ROOT SYSTEM – our assumptions about the very nature of reality (ontology) that are nurtured by the soil of our culture, practices and languages.

- TRUNK – our culturally encoded ways of knowing (knowledge system/epistemology)

- BRANCHES – our ways of organising this knowledge into disciplines and learning it (pedagogy) – physical sciences, biological sciences, social sciences, cultural studies, creative arts, religion, and the various vocational applications of these (academics, teachers, doctors, dentists, economists, accountants, engineers, scientists, psychologists, sociologists, anthropologists, priests, theologians, etc)

- LEAVES AND FRUITS – the values, social norms and ways of doing (outcomes/products/practices) that are derived from these ways of organising knowledge.

This is a picture of a Western knowledge tree. If we were to use it to describe an Australian First Nations knowledge tree, it would be very different at all levels. When we read about the multiple levels of meaning of ‘Caring for Country’ as expressed by First Nations peoples, this becomes readily apparent. One profound exposition of this can be found in the book, Songspirals, by the Gay’Wu Group of Women (2021) — a collaboration for over a decade between five Yolngu women of East Arnhem Land and three non-Aboriginal women from Macquarie and Newcastle universities.

First Nations peoples have been required to straddle these two knowledge systems as their world came under the authority of the ‘whitefella’ world via its legal system, property arrangements and institutions. Only now are non-Indigenous Australians being asked to make the reverse knowledge journey into profoundly different ways of being, knowing and doing—particularly when it comes to how we relate to the natural world in which we are intrinsically embedded, but which, culturally, we have experienced ourselves as masters of it, via our knowledges and practices.

If we only look at the tree above the ground – its trunk and branches (epistemology/ knowledge system), leaves and fruit (axiology/values and outcomes/products, ways of doing) and fail to understand its root system and soil (ontology – understanding of the very nature of reality), we will be constantly led astray. This is the profound insight we gain when we read Vanessa Machado de Oliviera’s Hospicing Modernity, referenced in a previous blog post.

As Bayo Akomolafe says about Oliviera’s confronting analysis of modernity and its impact: “navigating her rigorous work is an exercise in defamiliarizing modernity as the air we breathe, the site of our persistent illnesses, and the earthly thing that can give way to something else.”

Weaving Knowledge Systems Together

This Regenesis Blog has long advocated for the need to recognise that Australia is home to different knowledge systems, ending the hegemony of the Western knowledge system, with all its assumptions, as the only valid way of understanding reality. In The Regenesis Journey (2023), I have proposed that the new story of Australia should be forged on three principles (pillars):

- CARING FOR COUNTRY – bridge between First Nations’s idea of Country in all its multiple meanings and that of Western ecological sciences

- MULTICULTURALISM – inclusive of different ethnicities, religions faith traditions, knowledge systems and gender identity

- A CIRCULAR WELLBEING ECONOMY – transitioning to a zero-waste economy that delivers wellbeing to people, communities and our planetary home.

The western scientific knowledge system has deep roots in the rationalism of Greek philosophy and the mechanistic thinking that gained dominance with the 17th century Scientific Revolution, marked by Isaac Newton’s identification of the universal law of gravity in Principia Mathematica (1687) followed by Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution in On the Origin of the Species (1859). This established the primacy of the empirical investigation of phenomena (the scientific method) as the basis of valid knowledge, and its radical separation from non-rational religious faith.

The scientific method calls for the radical separation of the one who looks from that which is being looked at. It has also underpinned the rise and rise of the specialisation of knowledge into separate disciplines, each with their own ‘language’ and frames of reference that has prevented and disrupted attention to the interdependent nature of phenomena, revealed in the science of complex systems and ecological science.

But even in this domain, Western science remains strongly materialist and uncomfortable with the deeper eco-spiritual nature of First Nations knowledge systems which recognise that all of the phenomenal world is animated, charged with ‘spiritual presence’—an idea that is deeply uncomfortable to the Western rational tradition, and yet for which there is a deep yearning in many modern people, as evidenced in the ‘re-wilding’ movement and so-called alternative spirituality.

The result of the Western knowledge system has been a profound objectification of lived experience and the denial of other valid ways of knowing. This is now being challenged by First Nations scholars who are schooled in the Western empirical tradition based on objectification, yet who retain their First Nations cultural sensibilities that recognise that all of nature is ‘animated’, alive with spiritual presence, and where time does not only confirm to the linear nature of Western thinking which separates past, present and future. Instead there is a profound circularity of time and the past is ever present.

Underpinning the tragedy of the frontier wars of colonial dispossession of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people from their ancestral lands, was an epistemic genocide that attempted to wipe out their knowledge systems, language and cultural practices. Yet despite this violence perpetrated through the education and legal systems that condemned First Nations people to intergenerational psychic trauma and criminalisation, we are now witnessing a cultural renaissance of First Nations knowledge systems, as it seeks a ‘voice at the table’.

This Forum for re-imagining conservation—working together for a healthy Country, is one such expression of this renaissance. One which is already strong in the world of the creative arts through performing arts companies such as Bangarra and Marrugeku, in the work of Indigenous filmmakers and visual artists, and in the strength of First Nations voices in the music sector. For it is through the arts, through the songlines, that First Nations people kept their knowledge system alive across millennia.

Balpara: A Practical Approach to Working With Ontological Difference in Indigenous Land & Sea Management

In an articles published in Society & Natural Resources, Campion et al discuss the evolution of the Balpara system with the Bi and Yolngu people of Northern Australia, as a way of enacting the commitment to working with First Nations knowledge systems, in the reimagining of nature conservation in Australia.

https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2023.2199690

The authors note that despite great diversity among different First Nations peoples, which resists the Western knowledge systems attempt to establish universal truths, there is a broad commonality across many Aboriginal Australian nations. This commonality, in terms of a view of reality, consists of an interwoven matrix of place-based kinship relationships between people, plants and animals, and the living and non-living, that were initially laid down by creator beings and are sustained through everyday practices of renewal (Holmes and Jampijinpa 2013; Bawaka Country et al. 2013).

The creative vitality of these ‘creator beings’ can be best understood by the Western mind as the personification of the underlying creative forces of our planetary home: forces that can be ‘sung into presence’ through ceremony. Aspects of this form of knowing are familiar in all religious faiths, and which I have personally experienced through my own life as a student-practitioner in the Tibetan Buddhist wisdom tradition. Deities with all their symbolic meanings are personified expressions of timeless wisdom: wisdom teachers embody a continuous transmission of wisdom awareness across time and space; immersive spiritual practices allow one to ‘sing up’ these wisdom forces within our very being. When I speak with my Christian friends, this is their experience of the Eucharist, and although I have not discussed their inner spiritual experience with Islam and Hindu practitioners, from the poetry of their saints, I see that this is also true.

Double Separation

While Western ontologies are also diverse, there is an overarching and influential thread in Western experiences of reality, which has been what Ingold (2000, 15) refers to as the “double separation:”

—The first separation establishes a division between humanity and an external and universal “nature”

—the second between Indigenous people who live in “cultures” and Western people who ostensibly do not, for Western people have appropriated to themselves the idea that their knowledge system is based on universal truths, beyond culture. A blindness that has perilous implications.

The Campion et al article notes that these two separations and predominance of positivist scientific modes of evidence and meaning-making shape mainstream Western conceptions of knowledge. Science promises to provide an objective account of a biophysical reality that lies beyond any human or cultural perceptions of it.

The dual assumptions in contemporary Western ontologies of a universal biophysical world and the privileged position afforded to science make it more difficult for many contemporary Western knowers to live respectfully with ontological difference and divergence (Verran 2002, 2008; Blaser 2013). This makes a mockery of Australia’s claim to be a successful multicultural nation. For all too frequently, in our idea of what constitutes an authentic Australian identity, we revert to an unconscious assumption that our Constitution’s embrace of British culture is beyond culture—merely an extension of the ‘natural laws’ of science.

A genuine reconciliation with our Indigenous heritage means recognising and embracing the integrity of its knowledge system that has shaped the deep roots of this land for millennia.

In order to establish two-way learning that enables non-Indigenous nature conservationists to truly understand Indigenous ontologies, we must consider that: “in Yolngu and Bi ontological realities, the intergenerational relationships between plants, animals, people, language, stories and law are central to assessing and actively working to improve the “health” of a particular place.” Thus the Western scientific methods of categorisations, linked to data gathering and evaluation, fly in the face of this complex ontology of interdependencies that transcend the separation of nature, culture and family.

How do non-Indigenous practitioners escape the ‘double separation’ in the Western ontological position?

The general Western ontological position described in Ingold’s (2000) double separation establishes that Western knowers are seen as (exclusively) capable of establishing universal truths, while ontological Others (such as Bi and Yolnguk) are relegated to the position of subjects to be studied (Ingold 2000; Barbour and Schlesinger 2012; Blaser 2013). This problem has long plagued anthropology. It now plagues other ‘disciplines’ such as medicine, education, law, and land management.

This ‘othering’ extends even further into the more-than-human world, which in most Indigenous ontologies are regarded within the framework of kinship relationships, which are not exclusive to human kin. Thus ‘ethically’ we experience them as ‘resources’ to be managed ‘humanely’. We are a long way from the ‘hunter’, who honoured their kill through ceremony and kinship, when we debate the ‘live sheep trade’ or practices in abattoirs and intensive pig and chicken farming, which arrive packaged for consumption in our supermarkets.

On another dimension of this problematic of ontological differences, Emma Kowal’s Trapped in the Gap: Doing Good in Indigenous Australia (2015) explores the dilemma that non-Indigenous people such as herself, working in remote communities in the name of addressing social justice issues, become concerned that their efforts to improve the health and social status of Indigenous people might be furthering the neo‑colonial expansion of biopolitical norms in terms of economic participation, land management and institutionalised schooling.

The Balpara Approach

As outlined in the Campion et al article, the Balpara approach has slowly emerged over the past decade through several collaborative initiatives involving various members of the authorship group and many others concerned with the Arafura Swamp region in NE Arnhem Land. Balpara is a Rembarrnga word, which can be roughly translated in English as “partner” or “companion.” To give an example of everyday use, it is important that a Bi or Yolngu hunter has a balpara with them, to help track and collect fallen prey and to keep each other safe. The Balngarra clan decided to experiment by using the idea of wulken as a means of developing partnerships with non-Indigenous partners by inviting them to “walk and talk” on Balngarra Country—a transition from abstracted universal generalised knowledge, to the specificity yet greater complexity of ‘knowledge in place’.

The authors state that in principle, the concept of balpara might be used to guide any form of collaborative endeavour between parties in caring relationships. In the specific context of the IMEP (Indigenous Monitoring & Evaluation Plan) project, the authors used balpara to develop the “Balpara Camp” as a Bi and Yolngu monitoring method. We intended Balpara Camps to nurture partnerships between rangers and clans, and between rangers and external partners, in generating useful information for checking on the progress of ASRAC’s (Arafura Swamp Rangers Aboriginal Corporation) Healthy Country Plan.

Pluraversities NOT Universities

Learnings form the Balpara approach is that Western-trained ecologists or conservation biologists need to let go of their assumptions about the existence of a universal biophysical world that is separate to culture and accessible only through scientific epistemic practices and mechanisms. Secondly, they need to build on Howitt et al. (2013) and Muller (2014) in seeking enhanced intercultural capacity by honing competencies in working with ontologic pluralism.

They conclude that the danger lies in the “salvation narrative” in ILSM(Indigenous Land and Sea Management) apporach, which has the double effect of both under-estimating the capacities of Bi and Yolngu, while at the same time exaggerating the importance of non-Indigenous people’s capabilities in achieving desired outcomes. It is the author’s experience that Bi and Yolngu ways of being, knowing and doing are vastly different and often incommensurable, with Western ontologies.

For this reason, to truly engage in two-way learning, we need to move from the idea of universities as repositories of universal knowledge to pluraversities as repositories of diverse and place specific knowledges – ways of knowing, doing and being. This recognises that reality is made up of multiple worlds being nourished and cared for by Indigenous peoples and other local communities (Escobar 2011, 2016; Blaser 2013; Law 2015; Theriault 2017; De la Cadena & Blaser 2018; Wilson and Inkster 2018; Hope 2021; Paul et al. 2021).

![Call of the Dakini | A Memoir of a Life Lived [Extract]](https://regenesis.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Catalogue-OF-Articles-by-Barbara-Lepani-July-2018-July-2023-.jpg)

Recent Comments