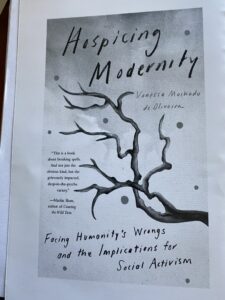

Hospicing Modernity

Facing Humanity’s Wrongs and the Implications for Social Activism (North Atlantic Books, 2021)

There is a growing realisation that we may now be facing the cultural dying of the modern era as a set of beliefs, knowledges, and institutional practices and structures that have shaped global societies since the 20th century with growing economic globalisation linked to technological innovation and consumption driven economic growth. It has been a ‘love affair’ with the idea of the ever ‘new’ set against the cultural drag of ‘tradition’.

The modern era has been closely associated with the increasing emphasis on individualism and urban cultural ideals, and a belief in the expanding possibilities of technological and political progress linked, in the West, to market-based liberal democracy, and to more autocratic solutions elsewhere. While these ideas are being tenaciously clung to in the dominant narratives of our society, there is now what the media calls a ‘trust deficit’—increasingly the promises of modernity feel hollow and fake. The promise of Facebook as promoting nurturing connected community turned into clickbait for marketing consumption and fake news, with industrialised chat bots taking the art of political propaganda to a whole new level.

Vanessa Machado de Oliveira’s Hospicing Modernity is probably the most confronting book that I have read in a while. It systematically demolishes the idea that within modernity’s all-encompassing functioning, solutions to its delusions and shadow venality can be found.

De Oliveira suggest that the end of the era of modernity as a global cultural-economic-political system of human endeavour may not manifest primarily as economic or ecological collapse, but as a global mental health crisis where the structures of modernity within us start to crumble (Chapter 10).

If, as Bayo Akomolafe suggests, we are to escape the stranglehold of the familiar and allow the imperceptible to blossom, de Oliviero suggests that we must collectively go through a clearing, a decluttering, an initiation into the unknowable. We must let go of our desires for certainty, authority, hierarchy, and of insatiable consumption as a mode of relating to everything—which are the marks of Modernity as a mode of being.

She points out that instead of the sort of metabolic literacy that has enabled First Nations cultures to speak with a thoroughly animated nature, modernity’s sensibility of knowledge-mediated hierarchical separability is based on human exceptionalism, transactional interactions and the expansion of human consumptive entitlements that has led to the extinction of countless beings, and now threatens the viability of human life in large parts of the Earth.

Re-wilding—The Escape Fantasy

At a time when Australians ponder over whether we will change our Constitution in response to the request of First Nations’ peoples’ Uluru Statement from the Heart, for a constitutionally enshrined right to a Voice to the Australian Government on matters that affect their lives, we are drawn to face the many contradictions of the Australian story:

- We celebrate our successful multiculturalism in the face of growing global ethno-nationalism AND YET, the underbelly of racism is bubbling up in this humble and modest ask for a constitutional right, through The Voice, to advise government and parliament.

- We talk about how we have the oldest continuous living culture in the world—that of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people whose settlement in Australia can be traced back around 65,000 years, well into the last Ice Age, AND YET so many of us refuse to listen to their voice.

- We struggle with the facts of our colonial history, which wreaked physical, cultural and epistemic violence on this culture—the effects of which continue through intergenerational trauma and high rates of criminal incarceration of First Nations people, particularly among the young for whom the pathways to the middle class wealth of the Australian Dream are narrow and blocked with many obstacles AND YET some claim colonialism left no negative marks.

- We talk about Closing the Gap in the statistical evidence of who does not enjoy the ‘good life’ of education, health services and jobs AND YET we bemoan the historical evidence that despite all the government expenditure, nothing seems to be working.

- We are invested in the idea of multiculturalism, AND YET most of us fail to see this must mean acknowledgement of different and competing knowledge systems—not just an appreciation of different ethnic food traditions, tolerance of non-Christian religious beliefs and anti-discrimination laws that seek to prevent racism and racially motivated hate crimes of speech and action.

- Many of us among the 76 percent, who have no First Nations cultural heritage, long to experience that deep sense of connection to Country, which First Nations people celebrate in their songlines, and which infuses their considerable contribution to our culture in the visual arts, music, theatre and film AND YET we continue to privilege mining companies and urbanisation over Caring for Country.

Many of us are inspired by the way in which Gina Chick won the Alone Australia competition for survival in the wilderness. Unlike her competitors who were intent on ‘conquering’ nature, she engaged with it, greeting the place where she was dropped off with love and humility. The response to her story reveals, she says that: “All around the country, the whisper of wildness is becoming a song, one we can all sing together, and hopefully in the echoes of that melody re-imagine our relationship with this planet, our only home.”

Gina is part of a ‘re-wilding’ movement among the privileged children of modernity who are seeking a new, anciently recovered, relationship with the natural world to heal their psyches. As she said in her ‘Australian Story’, “we adults are imprisoned by a thin veneer of civilisation telling us to control nature, to shape and mould and tame it, but inside, down where the wild things are, our instinctive voice whispers differently.” Her response to this, drawing on her own life journey has been to turn her own learning journey into a marketable ‘product’; the Wild Heart Program of ‘deep rewilding’ using her copyrighted system of 5Rhythms (meditation, emotional processing tools, ancient bushcraft skills and nature connections) as transformative practices that “bring people into harmony with themselves, each other and our living planet.”

Thus, born of an increasing awareness that the promises of modernity-civilisation have become a life-threatening trap, the solution offered is nevertheless packaged up as something for us to consume for a ‘price’, for those who can afford the money and the time.

Similarly, we hear about the power of ‘awe’ for healing our psyches, and so now there are people ‘hunting awe’, providing packaged tours to places that can deliver this to us. In this way the knowledges and rituals that are encoded in the First Nations cultures that coloniality has systematically sought to destroy, are extracted and packaged for consumption by those with the incomes and circumstances, in this age of the cost-of-living crisis, to take time out to ‘find themselves’—if only for a few stolen moments in time.

Escaping the Prison of Our Own Projections

De Oliveira warns us that our hopes in this solution are futile. We are still in the prison of modernity’s logic of insatiable consumption. People will seek out the knowledges of the formerly marginalised, but only to consume it in the search for ‘answers’ for how to either reform modernity, or to build a prefabricated alternative to it. But genuine teachings (knowledges) will be distorted by this market (for both sellers and customers) and the truth in it will be dissolved without people even noticing it.

We have seen this story before. It is a story pioneered by the Western hippy movement—the search for ‘alternative culture’ and ‘intentional off-grid communities’, which all too soon was coopted and incorporated into lifestyle culture and drug-enhanced experiences, morphing into its latest manifestation as the ‘wellness’ industry.

Instead, warns de Oliveira, “We will need a genuine severance that will shatter all projections, anticipations, hopes and expectations in order to find something we lost about ourselves, about time/space, about the depth of the shit we are in, about the medicines/poisons we carry. [For] this is about pain, about death, about finding a compass, an antidote to separability—about befriending death before we are ready to return home and to live as grown-ups”.

She warns we will want to overlook the complexities and paradoxes in our contexts and contradictions – “to polarize, antagonize, vilify and to romanticize and idealize.”

In her concluding chapter, ‘As Things Fall Apart’, after taking us on a long journey through Modernity’s paradoxes and blind alleys, de Oliveira concludes that facing the magnitude of the task of enabling a world without separability (between us and the land, and each other) requires more than a change of narratives, convictions and identities. It requires an interruption of harmful desires hidden behind promises of entitlements and securities that people hold onto, particularly when they are desperate and afraid.

For desperate and afraid we will become as global warming and geo-political conflict takes its toll. She suggests that in the face of this we must abandon our human-centric arrogance, decolonising our unconscious to allow our planet’s bio-intelligence to guide us, so that the land can ‘dream through us’. This will involve what Akomolafe calls ‘staying with the trouble’—the state of uncomfortable instability, of not knowing/understanding. Our unlearning will be long, hard and confusing.

The greatest danger, she identifies, is turning our inherent intuitive creative imagination into ‘creativity’, ready for co-option, consumption and reproduction of the status quo. For modernity’s colonisation of our unconscious means that, when left with a choice, most people will gravitate toward what is easier, most comfortable and most familiar—toward what will fulfill their modern desires while temporarily addressing their sense of depletion.

PERSONAL CHALLENGES

This brings her analysis home to me, for in my old age, replete with 35 years as a student of Tibetan Buddhism, and a student of the sociology of technological innovation, I now find myself running a community-based creative arts organisation in the Greater Blue Mountains. Can we in the arts sector, given license to transcend the dominance of rationality in the ‘economic’ sector, stay with the trouble enough to find ways to escape the all-encompassing embrace of commodification and consumption? Can arts praxis find ways to let the imperceptible to blossom? Can we find humour and humility in our grief?

De Oliveira reminds us that the death of modernity is not the end of the world, but the end of a harmful way of being, when we have finally become bored and disillusioned. For choosing reality over fantasy, facing the shadows, the storms and the shit is about humility, of de-idealising humanity to see our good, bad and the ugly, the beautiful and the messed up—the full complexity of life.

Modernity’s emphasis on individualism has led us into the trap of thinking we, the Self, are individual, singular and permanent. When, as my own learnings in Buddhist philosophy and contemplative investigation of mind reveal, we are interdependent, multiple and impermanent—part of the display of what de Oliveira calls, planetary-intelligence. We are not masters of the universe, but part of its dance. To be at peace with this requires letting go with humour, an ability to laugh at our absurdities. To embrace the lessons of the Trickster who refuses to surrender to the totalising rules of rationality.

Gina Chick has discovered this in her own learning journey. But in the way of the modern world, her learnings and offerings for others become commodified in ways that ‘fit in’ with modernity’s time frames and consumptive logic. And in so doing the so-called ‘wild’ becomes an adornment to the ‘tame’.

How do we really honour this ‘wild’ within, that aspect of ourselves that remains undomesticated by modernity’s corporate capitalist embrace. My Buddhist teachers introduced me to their own version of the Trickster – the dakini principle, the archetypal feminine as the great disruptor. ‘She’ calls out to us through all sorts of circumstances to WAKE UP, for the ‘wild’ within is actually our inherent, primordial wisdom intelligence, waiting to be called forth to express its nature as all pervasive non-dual lucidity replete with all-encompassing compassion.

Stages of Grief

In her study on how to better understand grief and dying, Elisabeth Kubler-Ross promoted the idea of understanding that there are five stages of grief, which became widely influential in western society, and the hospice movement which seeks to provide support to people facing death. These stages are denial, anger, bargaining, depression and finally, acceptance.

In the face of the impacts of climate change, wealth inequality, and increasing geo-political instability, are we witnessing the ‘end of the world’ of tech-consumption-driven wealth and comfort enjoyed by the so-called First World (of predominantly white privilege)?

- DENIAL Is our collective failure to respond adequately to the challenges posed by global climate change a sign that we are in the denial stages of grieving for the loss of the dream we have been sold by capitalism?

- ANGER Is the growing fractiousness in our community, the rise of far-right ethno-nationalism, the rancour of our national political response to the Uluru Statement from the Heart all signs of a rumbling anger?

- BARGAINING Is our search for new ‘sustainable’ technologies and renewable energy, as we continue on with consumption-driven economic growth part of our entering the bargaining stage of grief?

- DEPRESSION Is the growing mental health crisis of climate anxiety, particularly among the young, the signs of the depression stage?

- ACCEPTANCE And what will acceptance look like? Will it be ‘staying with the trouble’, the letting go of the need for certainty and control as our human ‘destiny’ as proof of our species superior intelligence, and learning how to be and flow with the complexity and uncertainties of life?

The idea of modernity was built on the triumph of scientific rationality over religious dogma, of a love affair with innovation and ‘the new’, a celebration of youth and beauty over old age and wisdom, of the promise that ‘we can all have it all’. It brought with it the feminist revolt against the assumptions of patriarchy and a global struggle about ‘human rights’ and ‘racial equality’ as global capitalism produced winners and losers, not only between nation states, but within nation states.

The European immigrant flows into the Americas and Australia that built their wealth, displacing and dispossessing Indigenous peoples, are now replaced by the reverse flow: non-European immigrant flows of refugees and asylum seekers. The ‘Third World’ is no longer ‘over there’, but here in our backyard, camped on our borders, desperately seeking the ‘safety’ and the ‘good life’ that the First World has projected about itself to the world.

Low income ‘white’ (Christian) Australians are shocked and challenged by the wealthy Chinese, Indians and Middle Eastern and Asian Muslims who are now amongst us. This is not the way of the world they were brought up to expect. The ‘social Darwinian’ assumptions of ethnic-cultural evolution placed the ‘white’ Nordic (Christian) people (the Aryans) on top of the natural hierarchy, the pre-literate (pagan) Indigenous peoples at the bottom. That Australia’s First Nations people are now demanding a reckoning about the ills inflicted on them by colonial settlement only adds fuel to the fire of collapsing assumptions. Particularly when they dare to suggest that their own knowledge systems hold truths that our sciences, for all their power, failed to recognise.

The Contradictions

The contradictions of Modernity’s claims are best illustrated by what has happened to food production and consumption. While medical science continues to explore new methods for ‘engineering’ our fight against disease with the promise of genetically targeted solutions and scientifically generated organ replacements, our scientific-food system continues to deliver increasing disease and morbidity.

While the affluent pockets of the West turn to veganism and organic foods and TV food shows, the food industry that feeds the masses has increasingly turned to ultra-processed foods, or what the Brazilian scientist Fernanda Rauber calls – ‘industrially produced edible substances’, These taste like food but are full of industrial substitutes for proteins, sugars, fibres and oils, combined with cosmetic additives—flavour enhancers, colours, emulsifiers, sweeteners, thickeners, bulking, carbonating, foaming, gelling and glazing agents. Scarce land resources in the Third World are expropriated and clear-felled to make way for palm oil plantations, with palm oil being one of the crucial ingredients in the Ultra Processed Food industry.

We are also told we have a growing food security crisis as people in parts of the world, particularly in war-torn Africa and scattered refugee camps, are literally starving, while other parts struggle with an epidemic of obesity, type-2 diabetes, tooth decay, kidney disease and other so-called lifestyle afflictions, as growing morbidity replaces mortality as the challenge for our health systems and ageing populations.

The Cultural Roots of Modernity

Modernity’s embrace of separability and human exceptionalism has deep roots in Western culture which can be traced back to Greek philosophy as it moved from an oral tradition to one of logocentrism, whereby the written word replaced contextualised knowledge, and set in train the project of universalised and abstracted knowledge, which accelerated following the17th Scientific Revolution and the search for the universal laws of nature. Which, once mapped and categorised, could be manipulated and exploited for our benefit.

The 18th century Enlightenment, the Age of Reason elevated human reason above religious belief as the pathway to valid knowledge, and an ‘arms race’ in the quest for ‘new’ knowledge through the scientific objectivist method of empirical investigation, replacing the established reliance on the authority of religious texts and customs. However, the emphasis on individualism, while liberating us from the constraints of the old order marked by patriarchy, misogyny and religious dogma, has progressively eroded the bonds of family and community, and the transactional ethos of market economies and private property has pitted self-advancement against the common good. Only too late have we begun to realise that the Enlightenment ideals of ‘liberty, equality and fraternity’ carried its shadow side, for these ideals could only be achieved on the back of the denial of ‘the other’, those trapped inside a continuing coloniality of extractive exploitation.

In ‘Hospicing Modernity’, we are asked to understand that modernity is a single story of progress, development, human evolution and civilisation that is omnipresent—full of paradoxes and contradictions. Of war and humanitarian support; of imperialism and education; of poverty creation and alleviation; of exponential growth and sustainability.

“Learning to offer palliative care to modernity dying within and around us is not something that modernity itself can teach us to do. . . However our collective unconscious knows that the enjoyments and securities promised by modernity cannot be endlessly sustained.”

It is this underling pervasive awareness that gnaws at humanity across the globe. How do we act with compassion to assist systems to die with grace and to support people in the process of letting go—even when they are holding on for dear life to what is already gone? Just as some wail at the unfairness of death of a loved one, others realise that death is an intrinsic part of life, of the way of the world at every level of existence.

Modernity’s Shadow—Coloniality

Drawing on the experience of First Nations peoples who remain as small pockets of resistance to modernity as marginalised ‘others’, de Riveira shows how modernity cannot exist without expropriation, extraction, exploitation, militarisation, dispossession, destitution, genocides and ecocides. For modernity rests on the deepest form of violence of all, reaching into our very sense of being, the imposed sense of separation between ourselves and the dynamic living land-metabolism that is the planet, as well as a theological separation between creature and creator—the very idea of separability based on human exceptionalism as a superior species, based on our supposed capacity for reason, language, philosophy and culture.

The deeper fault lines of modernity and the Enlightenment inheritance rest on two fundamental logics:

- The scientific method has inexorably led to the objectification of the world – the division of the one who knows/who is looking, from that which is known/being observed – in the search for ‘objective’ (factual) knowledge that seeks to be freed from subjectivity (feelings and ideological beliefs). The consequence of this radical dualism is the banishment of the possibility of intersubjectivity (intuitive feeling) as a way of valid knowing, aligned with a new mechanistic sensibility about the nature of the world; the shift from the idea of intrinsic value to utilitarian, transactional value.

- The increasing intensity of extractivist logic, aligned with the development of an economic and political system, which is bound up in the idea of productivity/progress – how to extract wealth for my/our benefit from: nature, you, human labour and human knowledge in the form of technology and science.

De Oliveira lays out how these two logics underpin modernity’s shadow side: coloniality—the enduring manifestations of colonial relations, logic and situations long after the official decolonisation of formal structures of governance. How it is a global hegemonic form of power that organises bodies, time, knowledge, relationships, labour and space according to economic parameters of transactional value to the benefit of particular groups of people with or without formal colonisation.

In the post imperial order, it is both the logic of political structures such as nation states, as well as relationships within and between such nation states and their constituent ethnicities. In their book, Silent Coup: How Corporations Overthrew Democracy, Claire Provost and Matt Kennard, identity the four pillars of this world order, which they identity as the neo-liberal Washington Consensus in search of greater industrial productivity (wealth creation):

- the international legal system – giving corporations the legal power to sue Nation States to protect their profits

- the international aid and development system – where aid became linked to a ROI in use of host corporate interests

- the corporate acquisition of territory – the special economic zones and tax havens

- the growth of private corporate armies – protection of assets in insecure ‘terrorist’ zones.

The result of these two logics spun across the world through imperialism and global capitalism is the great unravelling—of the promises of modernity and its dream of endless material progress giving us ease and comfort in the form of pleasurable ‘things’ and ‘experiences’; of a triumphant evolution of human ingenuity through science and its adaptation into technologies that will make us ‘masters of the universe’, and of a world of individual ‘freedom’. Of technologies that will enable us to conquer death; technologies that will enable us to escape the destruction of our planetary home’s bio-ecological limitations; to conquer other planets where we can begin again. Of technologies that will enable our evolution into technology-enhanced ‘super’ beings.

While some tremble with excitement at this prospect, aligned with our ability to colonise space, and overcome all challenges with technology and science, more and more of us tremble with psychic dread in the face of a global mental health crisis that will accompany modernity’s death throes.

![Call of the Dakini | A Memoir of a Life Lived [Extract]](https://regenesis.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Catalogue-OF-Articles-by-Barbara-Lepani-July-2018-July-2023-.jpg)

Recent Comments