Why is Tulkus, Tertons, Turmoil: East Tibet 1855-1955 an Important Story

Published on Amazon.com

Published on Amazon.com

Firstly it shows how the great 19th century spiritual renaissance of Buddhism in Kham, known as the Rimé (non-sectarian) period, occurred in a land rent by constant political turmoil, rather than in the romantic idea of ‘Shangri La’, a society of peace and harmony devoted to spiritual life. Thus it provides an inspiration to us, caught up in the fractious politics of climate change and contemporary geopolitics on the world stage, and continuous localised conflict in so many communities.

Secondly it honours the depth of spiritual wisdom that was nurtured in Kham and which is now available to the world through the Tibetan wisdom teachers who have made these teachings and practices available to people all over the world, and which are becoming of increasing importance to the people of China.

About this Book – Barbara Lepani (Author)

I began the research that led to this book Tulkus, Tertons and Turmoil: East Tibet 1855-1955 during the final year of a three year Buddhist retreat that I undertook between 2006 and 2009 at Lerab Ling, an international retreat centre in the L’Engayresque area of the south of France, just north of Montpellier an ancient centre of medical science and now a modern technopolis with an international airport and links on the TGV (fast train) to Paris.

Along with my professional life as a sociologist of science and technology specialising in technological innovation, since 1985 when I took Sogyal Rinpoche as my spiritual teacher, I have been a student-practitioner of Tibet’s Vajrayana Buddhism.

This spiritual journey took me into the Vajrayana knowledge system that allowed me to go beyond the worldview of scientific materialism that dominated my Western cultural inheritance. It also renewed my long interest in Asian history, when during my undergraduate university days I had studied the Cultural History of India and the History of the Far East: China and Japan from 1500 till WWII and the success of the Chinese communist revolution in establishing the People’s Republic of China.

As a result of this interest I joined a university student trip to China in 1968, during the early years of the infamous Cultural Revolution. In 2004 I returned to China, this time in the company of the Fifth Amnyi Trulchung Rinpoche, a young refugee Tibetan Buddhist teacher (lama) whom I met in New Zealand and whose household I came to manage, becoming his ‘adopted mother’ as he encountered the many cultural challenges of making a life for himself in the West. Passing through Chengdu, the provincial capital of Sichuan Province that now encompasses a vast area of East Tibet, it was a very different journey to that I undertook in 1968. In those days I knew nothing about Tibet and its history.

However, once I became a student of Tibet’s Vajrayana Buddhism, given my interest in Asian history, I also now became interested in the history of Tibet and its unique culture, which I first encountered through the life stories of the Tibetan Buddhist masters. Fortunately for me many of these stories have been published in the English language. Publishing houses such as Shambala, Wisdom, Snow Lion, Padma, and Rangjung Yeshe began publishing the teachings of Tibetan Buddhist masters and their life stories translated into English, while many university publishing houses, particularly in the US, began publishing scholarly works on Buddhism and the history of Tibet, including its relationship with China.

In particular I was inspired by the life stories of Padmasambhava and his spiritual consort, Khandro Yeshe Tsogyal, who were foundational figures in the establishment of Buddhism in Tibet during the 8th century and became important sources of my embodied mythopoetic engagement with the Vajrayana as my chosen spiritual path under the guidance of my root teacher, Sogyal Rinpoche. Jamyang Khyentse Chökyi Lodrö

Jamyang Khyentse Chökyi Lodrö

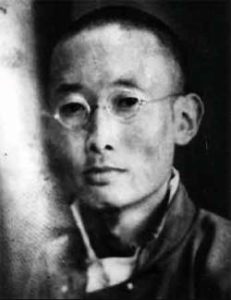

Sogyal Rinpoche’s root teacher was Jamyang Khyentse Chökyi Lodrö, the reigning tulku (reincarnated lama) of Dzongsar Monastery in the influential Derge Kingdom of Kham (East Tibet). Sogyal Rinpoche grew up in his labrang (lama household), where he joined his aunt, Khandro Tsering Chödrön who became Khyentse’s sangyum (spiritual consort). It was Jamyang Khyentse Chökyi Lodrö who recognised Sogyal Rinpoche as the reincarnation of Terton Sogyal Lerab Lingpa, an influential nagkpa (non monastic) lama who was part of the influential group of tertons, revealers of Padmasambhava’s hidden termas (treasure teachings) that played an important role in the non-sectarian Rimé renaissance during the 19th and 20th centuries, particularly in the Nyingma and Kagyu Schools of the Vajrayana. Terton Sogyal was also the Dzogchen teacher of the Thirteenth Dalai Lama.

Sogyal Rinpoche shared many stories of his times with Jamyang Khyentse Chökyi Lodrö, and through these stories we, his students, were taken into the life of one of the most influential masters of Kham, which whetted my appetite to know more about this world that had shaped their lives.

During my three-year retreat at Lerab Ling (2006-2009) I was given the opportunity to work closely with a German student, Volker Dencks, who had been similarly inspired by these stories and had spent several years tracking down Khyentse Rinpoche’s last remaining disciples still alive—living in Nepal, India and the US, and interviewing them on camera. He was also able to get these interviews transcribed and translated into English, as well as using a software program to scour the archives of Sogyal Rinpoche’s teachings to pull together all the mentions of this extraordinary Buddhist master. We students were also treated to a visit from Orgyen Topgyal Rinpoche during which he recounted the life and times of Jamyang Khyentse Chökyi Lodrö, taken from his own autobiography.

Although we worked together on a short anniversary video of the life of Jamyang Khyentse Chökyi Lodrö, the video quality of the interviews was not good enough to make a fuller documentary. Instead the transcribed and translated interviews, together with stories from the archives provided me with a rich resource for a written history. I divided his life story into four main periods: The Kathok Khyentse (1893-1909), Mastering Samsara and Nirvana at Dzongsar Monastery (1909-1926, Master 0f Masters (1927-1955), Ancient Tibetan Wisdom Meets the Modern World (1955-1959).

However I did not want to write a biography of this master. Such a task belonged to his disciples and reincarnations, such as Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche and Jigme Khyentse Rinpoche. And indeed, under the authorship of the great Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche, this was published as The Life and Times of Jamyang Khyentse Chökyi Lodrö: The Great Biography, by Shambala in 2017 under the guidance of Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche.

Instead I wanted to use the material that Volker had gathered to write a history of Kham (East Tibet) through the life stories of such masters, combined with the story of the political events that surrounded their lives, to give a social and political context to the world of the Buddhist masters during this important time in Khampa history. Thus I set about exploring other life stories and accounts of political events through many books and scholarly works such as PhD and Masters theses, as well as accounts by missionaries and other adventurers who had travelled in East Tibet during the 100 years before Kham became incorporated into the Peoples Republic of China, beginning with the arrival of the Chinese communist army into Kham in the early 1950s.Synopsis

Tulkus, Tertons and Turmoil: East Tibet 1855-1955 is told through the life stories of some of the leading Buddhist spiritual masters of East Tibet (Kham) as well as significant political figures active during this turbulent period in the history of Kham that now forms part of Sichuan Province, China.

It shows how the great non-sectarian spiritual renaissance during the Rimé period of Tibetan history in the 19th and early 20th centuries occurred in a land rent by constant political turmoil and thus serves as an inspiration in contemporary times of geopolitical tension.

It honours the spiritual masters of Tibet’s Vajrayana Buddhism, the tulkus (incarnate lamas) and tertons (revealers of treasure teachings) who have kept this unique wisdom knowledge tradition alive, both within contemporary China, and in the rest of the world through the Buddhist masters who came into exile where they attracted many student-practitioners and scholars across the world, both in the West and among the extensive Chinese and Tibetan diaspora. Within the PRC, many Tibetan and Han Chinese students are also seeking to study this Buddhist wisdom tradition in the important Buddhist Rimé centres of Larung Gar and Yanchen Gar in Sichuan, as well as across China.Buddhist Masters Featured in this History

Terton Sogyal, 1856-1926: A renowned nagkpa terton from Nyarong who became the Dzogchen teacher of the Thirteenth Dalai Lama, whose life he was said to have saved when at the age of 13 years he was a victim of political intrigue.

Terton Sogyal, 1856-1926: A renowned nagkpa terton from Nyarong who became the Dzogchen teacher of the Thirteenth Dalai Lama, whose life he was said to have saved when at the age of 13 years he was a victim of political intrigue.

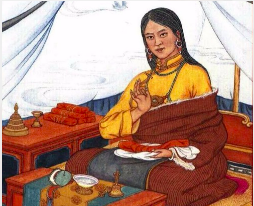

Sera Khandro Dewai Dorje, 1899-1952 (alternative dates 1892-1950): Female terton who came from an aristocratic life in Lhasa to live in Golok in her early teens to pursue her spiritual calling.

Sera Khandro Dewai Dorje, 1899-1952 (alternative dates 1892-1950): Female terton who came from an aristocratic life in Lhasa to live in Golok in her early teens to pursue her spiritual calling.

Jamyang Khyentse Chökyi Lodrö, 1893-1959: Activity incarnation of Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo (1820-1892) who took over his Sakya seat of Dzongsar Tashi Lhatse in the Kingdom of Derge in 1910, after the death of its young tulku, Jamyang Kyentse Chökyi Wangpo. Like his predecessor, he became a leading figure of the Rimé tradition in East Tibet.

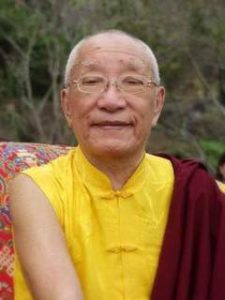

Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche, 1910-1991: Mind incarnation of Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo (1820-1892) who was enthroned at the Nyingma Shechen Monastery in Dzachuka and became a close spiritual friend of Jamyang Khyentse Chökyi Lodrö.

Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche, 1910-1991: Mind incarnation of Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo (1820-1892) who was enthroned at the Nyingma Shechen Monastery in Dzachuka and became a close spiritual friend of Jamyang Khyentse Chökyi Lodrö.

Garje Khamtrul Rinpoche, born 1928: Reigning tulku of Garje Khamu Monastery in Derge, who took up arms as part of the Khampa resistance then fled into exile, Traveling into the famed beyuls (sacred hidden valleys of refuge) of Guru Rinpoche before taking up residence in India and becoming the General Secretary of the Department of Religion and Culture in the Tibetan Government in Exile. Political Figures Featured in this History

Political Figures Featured in this History

Thubten Gyatso, Thirteenth Dalai Lama, 1876-1933: Ruler of Tibetan Lhasa Government, who in 1912 declared the independence of Tibet from Chinese claims of suzerainty.

Chao Erh-feng, 1845-1911: Chinese Magistrate sent by the Commander of the Qing army of Sichuan to suppress the Tibetan rebellion in the borderlands against Chinese rule, and who colonised much of Kham between 1905 and 1910, before being assassinated in Chengdu in the Chinese Republican uprising.

Chao Erh-feng, 1845-1911: Chinese Magistrate sent by the Commander of the Qing army of Sichuan to suppress the Tibetan rebellion in the borderlands against Chinese rule, and who colonised much of Kham between 1905 and 1910, before being assassinated in Chengdu in the Chinese Republican uprising.

General Liu Wenhui, 1895-1976: Chinese warlord who gained control of much of Kham from the 1930s until the Chinese communist invasion of Kham in the 1950s.

General Liu Wenhui, 1895-1976: Chinese warlord who gained control of much of Kham from the 1930s until the Chinese communist invasion of Kham in the 1950s.

Topgye and Rapga Pangdatsang: Two brothers of the famous Pangdatsang merchant family of Markham in Kham who twice led rebellions in search of Kham self rule from both the Tibetan Lhasa Government and the Chinese.

Bapa Phuntsok Wangyal, 1922-2010: Founder of the Tibetan Communist Party, born in Batang and educated in China, and saw communism as the means to modernise Tibet as an independent ‘soviet’ within international communism. Spent 18 years in solitary confinement in Beijing for the crime of local nationalism.

Bapa Phuntsok Wangyal, 1922-2010: Founder of the Tibetan Communist Party, born in Batang and educated in China, and saw communism as the means to modernise Tibet as an independent ‘soviet’ within international communism. Spent 18 years in solitary confinement in Beijing for the crime of local nationalism.

Gendun Chopel, 1903-1951: Regarded as a modern Tibetan intellectual before his time, he was a Tibetan monk-scholar, with incarnation links to Terton Sogyal, who navigated between the Nyingma and Gelug traditions, maintaining a strong non-sectarian view. He travelled to India to visit its holy sites, and assisted in the translation of the Blue Annals, a major Buddhist historical source, before becoming involved with the young Tibetan revolutionaries gathered at Kalimpong.Fourth Dodrupchen Rinpoche, Trinlay Palbar on the Fall of Tibet in 1959

Gendun Chopel, 1903-1951: Regarded as a modern Tibetan intellectual before his time, he was a Tibetan monk-scholar, with incarnation links to Terton Sogyal, who navigated between the Nyingma and Gelug traditions, maintaining a strong non-sectarian view. He travelled to India to visit its holy sites, and assisted in the translation of the Blue Annals, a major Buddhist historical source, before becoming involved with the young Tibetan revolutionaries gathered at Kalimpong.Fourth Dodrupchen Rinpoche, Trinlay Palbar on the Fall of Tibet in 1959

As Tibet refugees, including many Buddhist masters such as Jamyang Khyentse Chökyi Lodrö sought refuge in Sikkim as the communist armies swept into Tibet and declared ‘war’ on what they regarded as its feudal religious culture, the Fourth Dodrupchen Rinpoche, the main holder of the lineage of the Longchen Nyingtik Dzogchen tradition of teachings and practices, and who set up his new monastery in Gangtok, Sikkim, declared:

The whole world is changing before us like a magic show.

The whole world is changing before us like a magic show.

Appearances are unreliable like bubbles.

The monasteries, the loved ones in the Dharma, and the kin—

All have become mere memories.

Although I can see them, their fate is apparent.

Thinking this, I am sad.

I will exert all my efforts in earning the essence of the Dharma.

Holy teachers and kind friends

Were here just now, but, like gatherings at a fair,

Have disappeared, and I find myself alone, left behind.

Thinking this, I feel sad.

Placing the concepts of happiness and sadness in the emptiness sphere, and

Tossing worldly chores like camphor to the air,

I embrace the unexcelled sacred swift path,

Which is the heart-essence of dakas and dakinis, and

The crucial heart-artery of Dharmakaya, which has no reference point or basis.

I was fortunate enough to personally meet this great master, when I travelled to Sikkim in 1993 on a personal pilgrimage to meet Khandro Tsering Chödrön, the sangyum of Jamyang Khyentse Chökyi Lodrö, who had continued living here following his passing in 1959, until 2007 when she moved to live with her sister at Sogyal Rinpoche’s retreat centre, Lerab Ling, in France. She passed away there in 2011.The Legacy of the Tibetan Masters

The spiritual legacy of Jamyang Khyentse Chökyi Lodrö lived on in the work of his closest spiritual friend and disciple, Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche, in whom everyone recognised the living presence of the spiritual realisation of Jamyang Khyentse Chökyi Lodrö, and in his two principal reincarnations, Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche (b.1961) and Jigme Khyentse Rinpoche (b.1963). It has also informed the growing strength of the Rimé tradition amongst the masters teaching in exile in the West and India, and back in China.

This led to the renaissance of Tibetan Buddhism through the work of Jigme Phuntsok Rinpoche at Larung Gar, Akhyuk Rinpoche at Yanchen Gar, and Dr Lodrö Phuntsok at Dzongsar Monastery, as well as many other masters who have been involved in reviving the dharma in Kham and Tibet. Through the many thousands of monks and nuns of all traditions who came to study at Larang Gar and Yanchen Gar, the Rimé non-sectarian approach to the practice of Tibetan Buddhism has spread throughout the ethnic Tibetan and ethnic Han Chinese of China, and beyond.

An increasing number of scholars in China and the West have undertaken extensive postgraduate studies in Tibetan Buddhism and Tibetan culture, with schools of Tibetan Studies established in numerous universities around the world. Wangdrak Rinpoche from Gebchack Nunnery in Nangchen, who visited Australia in April 2016, reported that there is an increasing number of conferences now in China that are interested in the links between Buddhism and modern mindscience, particularly through the growing interest in neuroplasticity. With growing global concern about climate change, species extinction and issues of air pollution, water scarcity and soil degradation, there is also a growing interest in the intersection between the sciences of ecology and the Buddhist teachings on interdependence, such as is evident in the work of the Mind and Life Institute, established in 1987.

While Tibet, as a distinct geographically based ‘national’ identity may become subsumed into multicultural China, there is growing evidence that its culture, like that of many of the First World indigenous peoples, will continue to be a source of spiritual and social inspiration for many as a counterweight to the zeitgeist of technical rationality and ‘economism’ that is pervasive in the modern world.

It is a fervent hope that Chinese people of all ethnicities will come to value ethnic Tibetan areas (their Western Treasure House), not just for its vast mineral resources and economic opportunities, and for its wild natural beauty and exotica. Rather that they will also come to appreciate it for its rich spiritual heritage that is embedded in its language and its spiritual knowledge systems and the skilfull means of its spiritual practices—a spiritual wealth that is now part of the wealth of China, able to benefit all the people of China as it has benefited so many of us in the West.

![Call of the Dakini | A Memoir of a Life Lived [Extract]](https://regenesis.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Catalogue-OF-Articles-by-Barbara-Lepani-July-2018-July-2023-.jpg)

Recent Comments