Center for Humane Technology

We envision a world where technology is realigned with humanity’s best interests. Our work expands beyond tech addiction to the broader societal threats that the attention economy poses to our well-being, relationships, democracy, and shared information environment. We must address these threats to conquer our biggest global challenges like pandemics, inequality, and climate change.

CHT raises awareness and drives change through high-profile presentations to global leaders, public testimony to policymakers and heads of state, and mass media campaigns reaching millions. We also mobilize technologists as advocates and collaborate with top tech leaders through open and closed-door convenings.

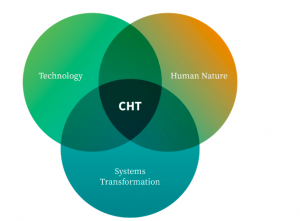

Working at the intersection of human nature, technology, and systems transformation, our goal is to shift the mindset from which persuasive technology systems are built, and to use that process to support crucial parallel shifts in our larger economic and social systems.

Our journey began in 2013 when Tristan Harris, a design ethicist at Google, observed the large-scale negative impacts of attention-grabbing business models. His presentation “A Call to Minimize Distraction & Respect Users’ Attention” went viral internally, reaching thousands of employees. Tristan extended the conversation publicly with two TED talks and a 60 Minutes interview, sparking the Time Well Spent movement. The number of concerned insiders was growing… Then, in 2016, the harms Tristan and others were warning of exploded into the public discourse with Russia’s use of social media to manipulate American voters.

Our journey began in 2013 when Tristan Harris, a design ethicist at Google, observed the large-scale negative impacts of attention-grabbing business models. His presentation “A Call to Minimize Distraction & Respect Users’ Attention” went viral internally, reaching thousands of employees. Tristan extended the conversation publicly with two TED talks and a 60 Minutes interview, sparking the Time Well Spent movement. The number of concerned insiders was growing… Then, in 2016, the harms Tristan and others were warning of exploded into the public discourse with Russia’s use of social media to manipulate American voters.

Building on that momentum, CHT launched in 2018 as an independent nonprofit. In the short time since, the landscape has dramatically shifted and the harms of tech platforms are laid bare for everyone to see.The Problem

Tech platforms make billions of dollars keeping us clicking, scrolling, and sharing. Just like a tree is worth more as lumber and a whale is worth more dead than alive—in the attention extraction economy a human is worth more when we are depressed, outraged, polarized, and addicted.See more info at Certified translations in London

Tech platforms make billions of dollars keeping us clicking, scrolling, and sharing. Just like a tree is worth more as lumber and a whale is worth more dead than alive—in the attention extraction economy a human is worth more when we are depressed, outraged, polarized, and addicted.See more info at Certified translations in London

This attention extraction economy is accelerating the mass degradation of our collective capacity to solve global threats, from pandemics to inequality to climate change. If we can’t make sense of the world while making ever more consequential choices, a growing ledger of harms will destroy the futures of our children, democracy and truth itself.

We need radically reimagined technology infrastructure and business models that actually align with humanity’s best interests.Principles of Humane Technology

Tech culture needs an upgrade. To enter a world where all technology is humane, we need to replace old assumptions with deeper understanding of how to add value to people’s lives.

Technology is never neutral.

We are constructing the social world.

Some technologists believe that technology is neutral. But in truth, it never is, for two reasons. First, our values and assumptions are baked into what we build. Anytime you put content or interface choices in front of a user you are influencing them; whether that is by selecting a default, choosing what content is shown and in what order, or providing a recommendation. Since it is impossible to present all available choices with equal priority, what you choose to emphasize is an expression of your values.

The second way technology is not neutral is that every single interaction a person has, whether with people or products, changes them. Even a hammer, which seems like a neutral tool, makes our arm stronger when we use it. Just like real-world architecture and urban planning influence how people feel and interact, digital technology shapes us online. For example, a social media environment of likes, comments, and shares shapes what we choose to post and reactions to our content shapes how we feel about what we posted.

Technology neutrality is a myth

Humanity’s current and future crises need your hands on the steering wheel.

To see the full implications of technology being values-laden, we must consider the vulnerabilities of the human brain. Many books have been written about the myriad cognitive biases evolution has left us with, and our tendency to overestimate our agency over them (see Resources). To quickly understand this, think of the last time you watched one more YouTube video than you had intended. YouTube’s recommendation algorithm is expert at figuring out what makes you keep watching—it doesn’t care what you intend to do with the next minutes of your life, let alone help you honor that intention.

Simple engagement metrics like watch time or clicks often fail to reveal a user’s true intent because of our many cognitive biases. When you ignore these biases, or optimize for engagement by taking advantage of them, a cascade of harms emerges.

Confirmation bias causes us to engage more with content that supports our views, leading to filter bubbles and the proliferation of fake news. Present bias, which prioritizes short-term gains, leads us to binge-watch as self-medication when we’re stressed instead of addressing the source of our stress. The need for social acceptance drives us to adopt toxic behavior we see others using in an online group, even when we would not normally behave that way.

Our vision is to replace the current harmful assumptions that shape product development culture with a new mindset that will generate humane technology. Integrating this new paradigm will mean process changes, time, resources, and energy within the product organization and beyond.

We realize systemic cultural change is never an easy task, with many opposing forces. Please reach out if you have ideas for how to help move this change forward or specific requests that you think CHT may be positioned to fulfill.Obsess Over Values

When you obsess over engagement metrics, you will fall into the trap of assuming you are giving people what they want, when you may actually be preying on inherent vulnerabilities. Outrageous headlines make us click even when we know we should be doing something else. Seeing someone has more followers than we do makes us feel inferior. Knowing our friends are together without us makes us feel left out. And false information, once we believe it, is very hard to displace.

Instead, you can be values-driven while still being informed by metrics. You can spend your time thinking about the specific values (e.g., health, well-being, connection, productivity, fun, creativity…) you intend to create with your product or feature. Those values can be a source of inspiration and prioritization. You can measure your success directly by investing in mechanisms of understanding that match the complexity of what you value, e.g. qualitative research and bringing in outside expertise.

QUESTIONS TO ASK YOURSELVES:

- What are the core values of your product? If you don’t have any yet, look to your vision for inspiration.

- If you were to center your design process around your product’s values, how might your features and processes be different?

- What kind of attitude shifts or behavior change might this product create? Do those changes align with your core values?

- What is a direct measure of success that you can use instead of relying on clicks/time spent/daily active users?

- How can you prioritize features using values as the criteria?

- How can you deepen your understanding of the values you have chosen for your product? Is there academic research you can take advantage of?

- Where is your product seemingly “giving users what they want”? What cognitive biases might be underneath?

Strengthen Brilliance

Not everything needs an upgrade. Under the right conditions, humans are highly capable of accomplishing goals, connecting with others, having fun, and doing many other things technology seeks to help with. Technology can give space for that brilliance to thrive, or it can displace and atrophy it. In each design choice, you can support the conditions in which brilliance naturally occurs.

For example, Living Room Conversations was created with the understanding that when people find similarities with each other and connect as human beings, they can more easily find common ground and shared perspective. Another example is online group technology like MeetUp that encourages in person get-togethers to deepen connections.

QUESTIONS TO ASK YOURSELVES:

- What inner capacities or resources make people feel well? How can technology strengthen those capacities without taking over people’s lives?

- For the values that you have chosen as a product team (e.g. connection, community, opportunity, or understanding), where in the real world can you find inspiration?

- How might technology help us overcome some of the greatest divides in our society (inequality, polarization, etc.)?

Make the Invisible Visceral

Ideally your organization would clearly understand the harms it creates and would perfectly incentivize mitigating them. In practice these harms are complex, shifting, and difficult to understand. Because of this, it is important to build a visceral, empathetic connection between product teams and the users they serve.

While many of today’s best practices use personas, focus groups, or “jobs to be done” to gain empathy for the user, humane technology requires that you internalize the pain your users experience, as if it were your own. Imagine the following scenarios:

- Your partner must be on board for the first flight of the plane you designed.

- Your mother ignores public health recommendations because of videos recommended by an algorithm you designed.

- Your middle-schooler is the subject of bullying on your social media app.

This mindset leads to a drive for deeper understanding and caution. It’s a mindset that your decision-makers and product team must share, for the many people impacted by your work: your users, the people around them (friends, family, colleagues, etc.), different socioeconomic populations (age, income level, disabilities, cultures, etc.), and so on.

QUESTIONS TO ASK YOURSELVES:

- Who are the stakeholders of your app or service beyond your existing users?

- Who using your app or service is being negatively impacted? What do you know about them?

- How can you give people with direct experience in the communities you are serving power in your decision-making process?

- If your solution is global, how can you understand how the user experience differs in other countries?

- What outside expertise can you bring in to help you with your chosen problem space?

Enable Wise Choices

As the world becomes increasingly complex and unpredictable, our capacity to understand our emerging reality and make meaningful choices can quickly become overwhelmed. As a technologist, you can help people make choices in ways that are informed, thoughtful, and aligned with their values as well as the fragile social and environmental systems they inhabit.

For example, when presenting new information, appropriate framing can help people make good decisions. The same information lands differently when framed in a more relatable context. Hearing that Covid-19 has a 1% case fatality rate might not mean much to you. But hearing that Covid-19 is several times deadlier than the flu, helps anyone immediately understand it in relation to something they already know. When people are presented with information in an intuitive way, they are empowered to make wise choices.

QUESTIONS TO ASK YOURSELVES:

- What choices are you offering your users? What framing are you using? How might a different frame lead users to make different choices?

- How can information be presented in a way that promotes social solidarity?

- How can we help people balance taking care of themselves with staying informed?

- How can we help people efficiently find the support they need?

Nurture Mindfulness

In a world where apps are competing constantly for our attention, our mindfulness is under attack. Mindfulness is being aware of, in a calm and balanced way, what’s happening in our mind, in our body, and around us. Mindfulness allows us to act with intention and to avoid a life that becomes a series of automatic actions and reactions, often based on fear and a scarcity mindset. But like any other capacity, mindfulness is one that can be developed. You can help your users regain and increase their capacity for awareness, rather than racing to win more of their attention.

For example, a mail application that by default makes a sound and puts up a notification when mail is received could instead have the user opt in to turn notifications on. Another example is the Apple Watch Breathe app, which supports people in periodically taking a moment to simply focus on their breath.

QUESTIONS TO ASK YOURSELVES:

- How can technology help increase capacities for concentration, clarity, and equanimity?

- How can technology foster a sense of agency and community?

- When are you vying for the user’s attention for the benefit of your product rather than for their benefit?

Bind Growth with Responsibility

Today’s technology has increasing asymmetric power over the humans that use it. Machine learning, micro-targeting, recommendation engines, deep fakes are all examples of technologies that dramatically increase the opportunity for creating harm, especially at scale. To mitigate this, you can invest in understanding the delicate cognitive, social, economic and ecological systems that your technology operates in, what harms your product may be generating, and ways to mitigate those harms.

For example, a product originally intended only for adults will almost inevitably be exposed to children as it scales; a platform originally intended for entertainment can become a target for disinformation; and a product that mostly benefits people in an industrialized country may mostly produce harms in a third world country. What feels like a remote possibility when you first launch becomes a guarantee as you scale to millions of people.

And even “good” things, when done to an extreme, will have unintended consequences. At first glance, Likes seem like a great signal about what the user wants to see more of. But at scale, it ends up creating filter bubbles and the fragmentation of shared truth.

QUESTIONS TO ASK YOURSELVES:

- How can you anticipate harms created by scale? What systems and processes will help you understand the impact of your product on its users and their larger social, economic, and ecological systems (for example, testing the product with a broad stakeholder set)?

- A/B testing is often compelling because it provides quick feedback to product decision-makers. Can you find similar solutions for tracking harms created by scale?

- If you are a platform for user-generated content, how can you avoid the mistakes made by previous platforms that led to widespread disinformation and other toxic content?

- If you are wildly successful creating the value you are trying to create, what is the failure mode that comes along with that? How can you safeguard against that? How can you find the ones you may have missed?

- At the end of every episode of Sesame Street, Elmo encourages kids to get up and do a dance so that they won’t watch another episode. How can you provide stopping queues so that users don’t overuse your product in a way that undermines what you value?

![Call of the Dakini | A Memoir of a Life Lived [Extract]](https://regenesis.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Catalogue-OF-Articles-by-Barbara-Lepani-July-2018-July-2023-.jpg)

Recent Comments