I feel as if this book, Sand Talk, by Tyson Yunkaporta is one I have been waiting for all my life—a book that probes into a whole different way of thinking and making sense of the world, without falling into the inevitable trap of having to talk about it in the language of another culture whose way of thinking denies it—the English language, its knowledge traditions (epistemology and pedagogy) and the whole trajectory of the narrative that Western Civilisation has crafted about itself as the ‘head prefect’ in the universe.

I feel as if this book, Sand Talk, by Tyson Yunkaporta is one I have been waiting for all my life—a book that probes into a whole different way of thinking and making sense of the world, without falling into the inevitable trap of having to talk about it in the language of another culture whose way of thinking denies it—the English language, its knowledge traditions (epistemology and pedagogy) and the whole trajectory of the narrative that Western Civilisation has crafted about itself as the ‘head prefect’ in the universe.

While Indigenous Australians are finding a way to tell the story of their cultural knowledge systems in a voice that we people of other worlds can understand —the Anglosphere and the recent migrants to our shores from Europe, Asia and the Middle East—we have to do our part to really hear what they are saying.[vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1569371004537{margin-top: 10% !important;margin-right: 10% !important;margin-bottom: 10% !important;margin-left: 10% !important;padding-top: 5% !important;padding-right: 5% !important;padding-bottom: 5% !important;padding-left: 5% !important;background-color: #ddc9a4 !important;}”]For an Indigenous Australian coming from an intensely interdependent and interpersonal oral culture, writing speech-sound symbols for strangers to read makes things even more complicated. That is exacerbated when the audience is preoccupied with notions of authenticity and the writer’s standing as a member of a cultural minority that has lost the right to define itself. The ability to write fluently in the language of the occupying power seems to contradict an Indigenous author’s membership of a community that is not supposed to be able to write about itself at all (Sand Talk, 2019:4)I grew up bog ignorant, a child of regional Queensland in the 1950s and 1960s. But I had a relentlessly questing mind that enabled me to throw off the shackles of my cultural milieu of overt racism and nativism, and eventually to see the full extent of the equally unconscious racism and Anglosphere ethnocentrism that defined Australian culture.

I felt like a stranger in my own home, so was always interested in exploring cultures other than my own. At university I not only studied European history and the history of the Americas (and its racism), but also the history of ancient India up until the time of British occupation and the history of the Far East – China and Japan. The latter saw me travel on a university student trip to Japan and China in the summer of 1967-68, right in the middle of China’s Cultural Revolution. That was an eye opener, destroying any romanticism about Maoism as the way to social and economic goodness.

Escaping the Queensland of Bjelke Petersen to live in Sydney, I finally got a ‘later years’ Commonwealth Scholarship that enabled me to complete my degree at the UNSW, this time majoring in sociology and history. By a strange accident of coincidences, it also led to cultural immersion in the Push Culture of the Sydney Libertarians and student politics through the campaign against censorship via the Tharunka student newspaper—both its official version and its underground version. I read the early Black writers like Franz Fanon (Black Skin, White Masks) and Ralph Ellison (The Invisible Man). These early writers of challenging the colonial narrative are credited with developing a profound social existential analysis of racism and the skewed rationality and reason in the dominant narratives of ‘white fella’ contemporary discourses on humanity. Then as fate would have it, on a demonstration about Aboriginal land rights to celebrate the Gurindji people’s reclaiming their country, I met a student from the Trobriand Islands of PNG, who later became my husband.And so I found myself in PNG at a time in its history when it was emerging from Australian colonial rule through self-government and then independence. With often socially painful and hysterical mishaps I found myself seeing my own people, White Australians, both the old colonial guard and the new breed of ‘development’ experts, through the eyes of PNG’s indigenous people. With the help of Malinowski’s anthropological studies, I began to understand my husband’s Trobriand Island culture from the inside—clumsily and very slowly because it was very difficult for me to give up the intellectual security of my own system of knowledge creation steeped in the confident English language tradition, and its strong attachment to the idea of ‘empirical facts’ and ‘objectivity’.[vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1569504036150{margin-top: 10% !important;margin-right: 10% !important;margin-bottom: 10% !important;margin-left: 10% !important;padding-top: 5% !important;padding-right: 5% !important;padding-bottom: 5% !important;padding-left: 5% !important;background-color: #ddcaa6 !important;}”]For as another great anthropologist, Gregory Bateson (Steps to An Ecology of Mind), has observed: In the natural history of the living human being, ontology and epistemology cannot be separated. His [commonly unconscious] beliefs about what sort of world it is [ontology] will determine how he sees it [epistemology] and acts within it, and his ways of perceiving and acting will determine his beliefs about its epistemological and ontological premises which—regardless of ultimate truth or falsity—become partially self-validating for him (Bateson, 2000:314).

Three events marked my passage to liberation from the blindfolds of my inherited ontology and epistemology. Visiting my in-laws in the Trobriand Islands for a ceremony to end the mourning for my husband’s grandfather, Chief of Vakuta Island, my father-in-law, Tomwagalisu said something that stopped me in my tracks. We were coming back from visiting some older women who were said to be masters of witchcraft, and therefore needing to be appeased by our offer of small gifts. It was dusk, that time of the day when bogwau, spirit sorcery, is active. All of my in-laws except for Tomwagalisu were visibly scared, as we travelled along a narrow path in thick jungle. So I asked him why he was unafraid. I expected Tomwagalisu to tell me about his protective magic, which my husband had assured me he had, but instead he turned to me and said: “I’ve noticed that you Dimdims (Europeans) are heavy to these things, so in my head I pretend I am a Dimdim.”

Later, back in Port Moresby where we lived, we were attending the funeral ceremonies for my husband’s cousin Dargi’s wife who had died from a ruptured spleen. This was the result of a physical argument with Dargi over her having given all their betal nut (a mildly addictive astringent stimulant that is used throughout Melanesia and India) to her relatives. Any death in a Trobriand Island family involves a whole sequence of gift exchange ceremonies between the relatives of the deceased and the relatives of the in-laws to re-weave the relationships that define their society. We had gathered at the house of another cousin who was a local doctor with a house on the hospital grounds. Dargi was inside, in a room with his children. We would all go in and cry with him, then come outside where Dargi’s relatives demonstrated their sorrow with the level of their wailing. Suddenly one old woman started talking, it was said in the dead wife’s voice. She said: “Do not blame my husband Dargi. It was not his kick that killed me. It was the betal nut. It was poisoned.” Of course I got this second hand as my husband translated for me, as I couldn’t speak their language. But I was outraged. “Of course her husband’s kick had killed her”, I insisted. “Ask your doctor cousin.” My husband looked at me as if I was stupid.

Later I reflected on this whole situation. Trobriand Island culture is matrilineal and maintained through a complex set of exchange relationships. All the children belong to the mother’s clan and it is her brother who is the ‘legal’ head of the family, not the biological father as in a patrilineal system. Thus when a garden is harvested, the first yams go to the sister’s family from the brother. When a death occurs, the crucial issue is to repair the net of exchange relationships, not to apportion blame from one event. Nothing is accidental; it is all seen through the prism of the network of interdependencies between clans, sub clans, land ownership, ritual obligations, etc. So yes, Dargi and his wife had got into an argument. Her spleen was swollen because of malaria that is rampant in the Trobriand Islands. So she was physically vulnerable to any scuffle that resulted in her being hit there. But, from a Trobriand cultural point of view, that was a small part of the total pattern of causation that needed to be taken into consideration. Many forces were at work. A Trobriand Islander would say: “Yes but many people get caught up in physical scuffles. Many people have had malaria. So why did she die in this particular instance? Something more had to be at work.”

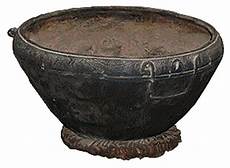

The third event that provided the final jolt to my confidence in simple empiricism and objectivism was an experience I had when visiting the Massim section of the Papua New Guinea Collection of artefacts in the Australian Museum on College Street in Sydney. I was now living back in Australia after my husband and I separated and had my two children with me. I gazed at the beautiful carved canoe prows of the Kula, and the magnificent clay pots from the Amphlett Islands that are part of the Kula Ring, my mind drifting back to a time when I had travelled on an outrigger canoe in these waters, with Tomwagalisu chanting magic incantations at the weather gods as we became engulfed in wild wind and rain.

The third event that provided the final jolt to my confidence in simple empiricism and objectivism was an experience I had when visiting the Massim section of the Papua New Guinea Collection of artefacts in the Australian Museum on College Street in Sydney. I was now living back in Australia after my husband and I separated and had my two children with me. I gazed at the beautiful carved canoe prows of the Kula, and the magnificent clay pots from the Amphlett Islands that are part of the Kula Ring, my mind drifting back to a time when I had travelled on an outrigger canoe in these waters, with Tomwagalisu chanting magic incantations at the weather gods as we became engulfed in wild wind and rain.

Suddenly the most extraordinary waves of energy seemed to emanate from these artefacts passing right through me, seemingly opening a new door in my mind with a huge question. What does it mean to know—what is this mysterious business of ‘knowing’? This experience was so profound that it led me to quit my job and go on what I called my ‘journey into the epistemological abyss’, a journey that completely changed the course of my life.Tyson Yunkaporta had to go on his own journey into the epistemological abyss. It took him from his birthplace in Melbourne, moving north, growing up in a dozen different remote or rural communities all over Queensland, ‘eventually unleashed on the world as an angry young male, in a flurry of flying fists and cultural dysphoria’, to his formal adoption under Aboriginal law into the Apalech clan from Western Cape York in northern Queensland. From the security of this base, Tyson worked with Aboriginal languages, schools, ecosystems, research projects, wood carvings, philanthropic groups and songlines, forming close bonds with a lot of Elders and knowledge-keepers across Australia who taught him more about the old Law, the Law of the land. (Sand Talk, 2019:8).

In Sand Talk, Tyson seeks to talk about the processes and patterns he knows from his cultural practice, developed within his affiliations with his home community and other Aboriginal communities across Australia, including Nyoongar, Mardi, Nungar and Koori Peoples. Here he seeks to reverse the lens, examining global knowledge systems from an Indigenous Knowledge perspective, grounded in its oral cultures, and ‘sand talk’—the Aboriginal custom of drawing images on the ground to convey knowledge. In this he seeks to convey the meta-story that connects and extends all over Australia through massive songlines in the earth and sky, a Star Dreaming that Jumo Fejo, whom Tyson calls Oldman Juma from the Larrakia People wants to share with all Peoples (Sand Talk, 2019:18).

Tyson eschews the normal approach of focusing on instances of Aboriginal culture through isolated examples of painting and ceremonies. Rather he seeks to use an Indigenous pattern-thinking process to critique contemporary systems and to impart an impression of the pattern of creation itself. As he says, ‘this book is just a translation of a fragment of a shadow, frozen in time’—an example of how literacy (the written word) freezes time in a linear straight jacket, compared to oral culture (story telling) that moves with non-linear time. He grapples with the conundrum of trying to use the English language, and its binary structure of subject/object, which inevitably places settler worldviews at the centre of every concept, to talk about a non-linear, process-oriented, pattern-making worldview. Tyson is dealing with the whole colonial project of not just power domination but epistemic domination. Here in this image Tyson seeks to capture the difference between text-based literate cultures (hand held sideways) and oral-based pattern thinking cultures (fingers splayed) – an image often stencilled in Aboriginal rock carvings.

[vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1569474472246{margin-top: 10% !important;margin-right: 10% !important;margin-bottom: 10% !important;margin-left: 10% !important;padding-top: 5% !important;padding-right: 5% !important;padding-bottom: 5% !important;padding-left: 5% !important;background-color: #ddc796 !important;}”]The colonial expansion of Europe was an exercise in domination, and while military and economic control was paramount, epistemic control was a full partner in keeping the colonial subjects docile and subservient… The European [EuroAmerican] intellect is committed to the world of representation. Its truth does not lie in experience but in words, in the logos, and in formally validated logic… Is not rationality in the West always instrumental rationality… the value-free theory of European rationality is only a myth? (K. Liberman, Dialectical Practice in Tibetan Philosophical Practice: An Ethnomethodological Inquiry into Formal Reasoning, 2004: 7-19).

[vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1569474472246{margin-top: 10% !important;margin-right: 10% !important;margin-bottom: 10% !important;margin-left: 10% !important;padding-top: 5% !important;padding-right: 5% !important;padding-bottom: 5% !important;padding-left: 5% !important;background-color: #ddc796 !important;}”]The colonial expansion of Europe was an exercise in domination, and while military and economic control was paramount, epistemic control was a full partner in keeping the colonial subjects docile and subservient… The European [EuroAmerican] intellect is committed to the world of representation. Its truth does not lie in experience but in words, in the logos, and in formally validated logic… Is not rationality in the West always instrumental rationality… the value-free theory of European rationality is only a myth? (K. Liberman, Dialectical Practice in Tibetan Philosophical Practice: An Ethnomethodological Inquiry into Formal Reasoning, 2004: 7-19).

For a detailed exploration of colonialism and epistemic control, see Linda Tuhiwai Smith’s Decolonising Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples, University of Otago Press, 1999.After my museum mind-opening experience, my own journey into the epistemological abyss saw me return to Papua New Guinea to revisit this land of my first awakening, and then plunge into the growing feminist literature challenging the male-centred worldview that has dominated the Western literary and historical narrative. From Germain Greer’s ground breaking Female Eunuch (1970) to the wild side in authors like Dorothy Dinnerstein, The Rocking of the Cradle and the Ruling of the World (1976), Barbara Walker, The Woman’s Encyclopedia of Myths and Secrets (1983), Clarissa Pinkola Estés, Women Who Run With the Wolves (1992) and eco-feminists such as Carolyn Merchant, Death of Nature (`1980) and Mary Daly, Gyn/Ecology (1978). I dived into the writing of Carl Jung who inspired Joseph Campbell’s exploration of the role of mythic metaphors across cultures, with his archetype of the Hero’s Journey forming an essential role in the narrative structures of the movie industry as the great engine of western cultural expression. Meanwhile, grasping the transformative power of technology, I studied for a Masters Degree in Science and Technology Studies, which led me into literature in the History and Philosophy of Science. Here I came to understand that the essence of the mechanistic worldview lies in its assumption of fixed basic qualities, which means that the laws themselves will finally reduce to purely quantitative relationships—one of the major projects of the discipline of economics in search of being a ‘science’.

I had many dreams, one of which led me to ask my neighbour to teach me how to make ceramic fertility sculptures for my garden as a counter to the ‘masculinity of science’ and its story of instrumental reason. I learned to use the language of art, moulding Earth’s flesh into vessels and then consigning them into the alchemy of fire in the kiln. I plunged into the world of mythopoetic form both mentally and physically and felt its liberating energy.

Then I came to a point where I knew I couldn’t just read my way into exploring the ‘epistemological abyss’—that I was trapped, turning around and around in the ‘clothes dryer of my mind’. I realised I was in fact on a spiritual journey and I needed to find a teacher who could challenge my intellectualising mind at a fundamentally gestalt level. In the middle of an emotional and physical falling apart, I took myself off to listen to a public talk by a visiting Tibetan lama, Sogyal Rinpoche, on Turning Suffering and Happiness into Enlightenment.

Fortune smiled on me, as in this teacher I found my gestalt level challenge and for the next 33 years until his recent death in 2019, I became his student in the extraordinary knowledge system and pedagogy that is Tibetan Buddhism, the vehicle of the Vajrayana and Dzogchen, the diamond vehicle that slices through delusion and ignorance to reveal a whole different way of knowing and being, that of non-conceptualising pure awareness. It’s been a wild ride. Sogyal Rinpoche’s methods were unorthodox. He combined a mastery of the English language with direct methods that worked on an altogether different level—the magical level of spiritual transmission kept alive through the centuries in the student-teacher relationship bound by the idea of samaya—a sacred bond of trust that respects the secrecy provisions that are part of Vajrayana transmission of knowledge and practice. With samaya, the teacher commits to liberating the disciple from the prison of their reifying ego-mind, what Tyson calls Emu; and the student commits to following the instructions of the teacher no matter how strange they might seem, having a strong commitment that they want to be released from this way of experiencing themselves and the world around them. There has to be trust both sides, and of course that trust has to be grounded in the sanity of one’s own ethical values.When I later worked with Tjilpi Bob Randall of the Yankunytjatjara people of Uluru on his autobiographical book published as Songman, it was my immersion in the Vajrayana tradition that enabled me to have some understanding of the world of Aboriginal Australia that Bob was talking about for his book. Through my own Buddhist practices that use song, dance, and mythic story structure to enable me to experientially enter into a particularly way of ‘being’ and ‘seeing’, I have some inkling of what happens when an Aboriginal person enters into their totemic relationship through certain ceremonies of their songline. When I asked Bob about the purpose of secrecy in the transmission of Aboriginal knowledge and Law, he explained to me: “It is not something you are meant to talk about (gossip); it is meant to transform your very being”, which is exactly the same purpose as in Vajrayana knowledge transmission. I don’t have a totem, but I do have a spiritual practice that provides me with a mandala of spiritual knowledge, a sacred pattern as a way of ‘being’ in the world, and I have some sense of non-linear time and a way of being that transcends time and space in the ordinary sense of Western culture.

One of my Buddhist teachers has also recognised a certain rock formation near where I live as a manifestation of a Buddhist female deity who is part of my mandala, and at the same time this rock formation is part of the Seven Sisters Dreaming of Aboriginal culture. And in this way the circle of my life linking the world of Tibet and Australia is joined in a magical way.

I think that the relationship between the knowledge holder elders of the Indigenous culture and that of their initiates, through the long process of learning the songlines, has some similarities with the idea of samaya in Tibetan Buddhism. Tyson explains in Sand Talk, how Aboriginal songlines are ancient paths of the Dreaming etched into the landscape in song and story and mapped into Aboriginal people’s minds and bodies and relationships with everything around them: knowledge storied in every waterway and every rock, which is alive with sentient presence—according to the knowledges that have been transmitted to them through stories and ceremony. In this way as Tyson explains, all these stories and connections tell us about how to deal with the complexities and frailties of human societies, how to limit destructive excesses in these systems, and most importantly how to deal with ‘idiots’, the human virus of narcissism—self centredness and the anxiety it produces around hierarchies of power and influence, embodied in the figure of Emu, the troublemaker who brings into existence the most destructive idea in existence: I am greater than you; you are less than me (Sand Talk, 2019:30).[vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1569372842786{margin-top: 10% !important;margin-right: 10% !important;margin-left: 10% !important;padding-top: 5% !important;padding-right: 5% !important;padding-bottom: 5% !important;padding-left: 5% !important;background-color: #ddc49b !important;}”]You can see the dark shape of Emu in the Milky Way. Kangaroo (his head in the Southern Cross) is holding him down, Echnida is grasping him from behind, and the great Serpent is coiled around his legs. Containing the excesses of malignant narcissists is a team effort ((Sand Talk, 2019:31).The competitive nature of modern society—for jobs, assets, wealth, fame, even belonging and identity, places a terrible strain on us, exacerbated by the mirror of social media with its selfies, memes and clickbait. The idea put forward by our Prime Minister, steeped in the ‘prosperity doctrine’ of evangelical Christianity that only ‘those who have a go deserve a go’, the ‘survival of the fittest’. The rest are just the losers (sinners) of society, the welfare cheats and drug addicts to be pursued by robodebt collection. As one educator noted in a media article, this cultural meme, which also underpins the failure of modern society to respond to the climate change crisis, is producing increasing levels of anxiety and depression in our children and with it, rising levels of narcissism and rage against the ‘enemy other’.[vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1569372857580{margin-top: 10% !important;margin-right: 10% !important;margin-bottom: 10% !important;margin-left: 10% !important;padding-top: 5% !important;padding-right: 5% !important;padding-bottom: 5% !important;padding-left: 5% !important;background-color: #ddcba8 !important;}”]Recent studies in the United States show that empathy in young people has dropped by almost 50 per cent since the 1980s and 1990s. In fact, as Professor Peter Gray points out, about 70 per cent of students score higher on narcissism and lower on empathy today than the average student did 30 years ago (Mariana Rudan, ABC News Online, 25 September 2019).Tyson makes a compelling link between Indigenous ways of thinking and knowing and recent scientific theories of complexity and self organising systems and the fractal mathematics of non-linear systems. He suggests that the big bang pattern of creation, that initial point of impact, is not just something that occurs at the massive scale of the universe, but is repeated infinitely in all its lands and parts.

I think that the relationship between the knowledge holder elders of the Indigenous culture and that of their initiates, through the long process of learning the songlines, has some similarities with the idea of samaya in Tibetan Buddhism. Tyson explains in Sand Talk, how Aboriginal songlines are ancient paths of the Dreaming etched into the landscape in song and story and mapped into Aboriginal people’s minds and bodies and relationships with everything around them: knowledge storied in every waterway and every rock, which is alive with sentient presence—according to the knowledges that have been transmitted to them through stories and ceremony. In this way as Tyson explains, all these stories and connections tell us about how to deal with the complexities and frailties of human societies, how to limit destructive excesses in these systems, and most importantly how to deal with ‘idiots’, the human virus of narcissism—self centredness and the anxiety it produces around hierarchies of power and influence, embodied in the figure of Emu, the troublemaker who brings into existence the most destructive idea in existence: I am greater than you; you are less than me (Sand Talk, 2019:30).[vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1569372842786{margin-top: 10% !important;margin-right: 10% !important;margin-left: 10% !important;padding-top: 5% !important;padding-right: 5% !important;padding-bottom: 5% !important;padding-left: 5% !important;background-color: #ddc49b !important;}”]You can see the dark shape of Emu in the Milky Way. Kangaroo (his head in the Southern Cross) is holding him down, Echnida is grasping him from behind, and the great Serpent is coiled around his legs. Containing the excesses of malignant narcissists is a team effort ((Sand Talk, 2019:31).The competitive nature of modern society—for jobs, assets, wealth, fame, even belonging and identity, places a terrible strain on us, exacerbated by the mirror of social media with its selfies, memes and clickbait. The idea put forward by our Prime Minister, steeped in the ‘prosperity doctrine’ of evangelical Christianity that only ‘those who have a go deserve a go’, the ‘survival of the fittest’. The rest are just the losers (sinners) of society, the welfare cheats and drug addicts to be pursued by robodebt collection. As one educator noted in a media article, this cultural meme, which also underpins the failure of modern society to respond to the climate change crisis, is producing increasing levels of anxiety and depression in our children and with it, rising levels of narcissism and rage against the ‘enemy other’.[vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1569372857580{margin-top: 10% !important;margin-right: 10% !important;margin-bottom: 10% !important;margin-left: 10% !important;padding-top: 5% !important;padding-right: 5% !important;padding-bottom: 5% !important;padding-left: 5% !important;background-color: #ddcba8 !important;}”]Recent studies in the United States show that empathy in young people has dropped by almost 50 per cent since the 1980s and 1990s. In fact, as Professor Peter Gray points out, about 70 per cent of students score higher on narcissism and lower on empathy today than the average student did 30 years ago (Mariana Rudan, ABC News Online, 25 September 2019).Tyson makes a compelling link between Indigenous ways of thinking and knowing and recent scientific theories of complexity and self organising systems and the fractal mathematics of non-linear systems. He suggests that the big bang pattern of creation, that initial point of impact, is not just something that occurs at the massive scale of the universe, but is repeated infinitely in all its lands and parts.

In this way Tyson suggests that Uluru is the stone at the centre of this continent’s story, a pattern repeated in the interconnected and diverse stories of many smaller regions, reflected in our own bodies at the navel and then down into smaller and smaller part at the quantum level of our cosmology (Sand Talk, 2019:29). It is certainly true that Uluru exerts a powerful pull on the Australian imagination, a magnetising presence in our desert heartland.How do we think about time? In the Western tradition, we think of time as linear and passing from past to present to an expected future. But for people anchored in the cycles of nature and the Earth, time is more circular and constantly in motion. The morning sun will set but then it will rise again and the seasonal weather patterns interact with the behaviour of life forms embedded in different, layered ecosystems. In this way Creation is in a constant state of motion; it is a dance. We must move with it as the custodial species or we will damage the system and doom ourselves (Sand Talk, 2019:45). This is evident in the looming existential crisis signalled by global warming, resulting from the Ways of Thinking that underpin the modern economic project that grew out of the industrial revolution, but has its mental roots deep in the binary nature of the dominant Western viewpoint—the subject/object split that creates a reified experience of reality.

We have been beguiled by the scientific quest to nail down the rules of life so that life can be dissected and manipulated for human purpose; that ‘Truth’ as per the Abrahamic religions of the book can be found in a book recording God’s words (Torah, Bible, Koran), rather than the deep knowing of the way Creation actually works as evidenced in nature’s ecological systems. The Western knowledge project thought the Bible gave it a ‘fix’ on things. This was then displaced by science—Copernicus on the nature of the heavens followed Newton’s use of mathematics to map out the clockwork nature of a mechanistic universe devoid of mythic presence. These certainties were then blown apart by Einstein’s revelation of the relativity of time and space, followed by more and more revelations that revealed the Uncertainty Principle that destroyed the subject/object split, fractal mathematics that revealed a world of patterns, and a growing understanding of the nature of life as multi-layered emergent, complex systems. It is not about getting a handle on step changes from one stable system to another, much loved by organisational theory, but learning how to flow—to move and adapt within a system that is in a constant state of movement and adaptation (Sand Talk, 2019:49). These same ideas are known in the Ways of Thinking of many Indigenous peoples and in Chinese Taoism and Buddhism, but are resisted by Western ways of thinking, which are driven by a need for ‘control’—what Tyson calls the Emu problem.[vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1569506611272{margin-top: 10% !important;margin-right: 10% !important;margin-bottom: 10% !important;margin-left: 10% !important;padding-top: 5% !important;padding-right: 5% !important;padding-bottom: 5% !important;padding-left: 5% !important;background-color: #ddc7a1 !important;}”]First People’s Law says that nothing is created or destroyed because of the infinite and regenerative connections between systems. Therefore time is non-linear and regenerates creation in endless cycles. . . We need to be brave enough to apply it to our reality of infinitely interconnected, self-organising, self-renewing systems. We are the custodians of this reality, and the arrow of time (linear idea of Progress) is not an appropriate model for a custodial species (such as we humans) to operate from (Sand Talk, 2019:52-59).Tyson calls to mind the extraordinary metaphor of the Rainbow Serpent in Indigenous culture, a mythic creature that is constantly in motion across systems and interwoven throughout everything that is, was and will be—a creature of water, of light, of stone, of the underground and of the sky—moving through the ‘photo-fabric’ of creation (p. 55). As Tyson notes many cultures recognise this mythic form. It is the dragon, the wyrm, the Uraeus and the Naga, the entwined form of DNA, the code of living forms.

He also warns that as we attempt to learn from Indigenous Knowledge and incorporate it into our ways of thinking, we can easily contaminate it—that while the physical apocalypse of invasion came with a bang, for Indigenous Australians, their cultural Armageddon is more of a whimper subject to a gradual contamination and unravelling of communal knowledge through so-called Dreaming stories, shamanic rituals, and other forms of cultural appropriation. He argues that while culture is always evolving and adapting, real cultural innovations occur in deep relationships between land, spirit and groups of people, for the ‘song’ itself is not as important as the communal knowledge process that produces it, the practices and forms that evolve through the daily lives and interactions of people and place in an organic sequence of adaptation.

Tyson warns that the greatest danger facing Indigenous Knowledge systems is their ‘adoption’ by modern society because of the extraordinary ability of ‘liberalism’ to absorb any object or idea, alter it, sanitise it, rebrand it and market it (Sand Talk, 2019:71-74). I have seen this process at work with Tibetan Buddhism. Methods developed to liberate us from ego-reification are adapted and rebranded as mindfulness techniques to help people be more successful in the modern workplace. While the world faces a global crisis of climate change and species extinction, the modern project of organising the world into nation states, whereby Donald Trump, President of the United States can declare that the world does not belong to globalists but to patriots, means that humanity cannot respond to the crisis of their own creation—and that many First Nations peoples find themselves stranded as minorities within these nation states, at the mercy of their laws and cultural memes.

We are left with the haunting words of the 16 year old Greta Thunberg in her address to the United Nations Climate Summit (September, 2019):[vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1569457005247{margin-top: 10% !important;margin-right: 10% !important;margin-bottom: 10% !important;margin-left: 10% !important;padding-top: 5% !important;padding-right: 5% !important;padding-bottom: 5% !important;padding-left: 5% !important;background-color: #ddc9a1 !important;}”]You are still not mature enough to tell it like it is. You are failing us. But the young people are starting to understand your betrayal. You have stolen my dreams and my childhood with your empty words. The eyes of all future generations are upon you. And if you choose to fail us I say we will never forgive you. We will not let you get away with this. Right here, right now is where we draw the line.Drawing on Indigenous Knowledge systems and the Oldman Juma’s patterns, Tyson calls on us to rediscover pattern thinking, to read patterns and see past, present and future as one time. To discover that the real understanding comes in the spaces in between, in the relational forces that connect and move between points, to follow the patterns of creation, to develop governance systems based on respect for social, ecological and knowledge systems and all their components or members because knowledge is a living thing that is patterned within every person and being and object and phenomenon within creation (Sand Talk, 2019:95)

What process can we use to follow this instruction? Tyson suggests there are four: connect, diversify, interact and adapt, which lead to a process suggested by Noongar Aboriginal Elder, Mumma Doris Shillingsworth: Respect, Connect, Reflect and Direct. Tyson also suggests that knowledge transmission must connect both abstract knowledge and concrete application through meaningful metaphors in order to be effective—working with grounded, complex metaphors that have integrity is the difference between decoration and art, tunes and music, commercialised fetishes and authentic cultural practice. When metaphors have integrity they are multi-layered, with complex levels that may be accessed by people who have prerequisite understandings (Sand Talk, 2019:118).

From here Tyson takes us to consider the importance of story-mind, a way of thinking that encourages dialogue about history from different perspectives as well as the raw learning power of narrative itself, based on the idea of ‘yarning’, a back and forth process of active listening. This is non-linear allowing the conversation to branch off into diverse themes and topics, using story, humour, gesture and mimicry. For the endpoint of a yarn is a set of understandings, values and directions shared by all members of the group in a loose consensus that is inclusive of diverse points of view. An extraordinary example of this process is the Uluru Statement from the Heart, whereby diverse Indigenous people from across Australia reached a consensus on a way forward for Australia to deal with its history of dispossession and the cultural genocide of its Indigenous peoples—Voice enshrined in the Constitution, Truth Telling about our collective history, and Treaty.This brief journey through Tyson Yunkaporta’s Sand Talk does not do it justice. You need to fully read and reflect on this important book. But to pick up the story from Mumma Doris, we can conclude with a process to shape a journey towards a way forward among collective groups of people in all walks of life:

RESPECT—aligning with values and protocols of introduction, setting rules and boundaries, the work of your spirit and your gut

CONNECT—establishing strong relationships and routines of exchange equal for all involved so that your way of being is your way of relating, the work of your heart

REFLECT—thinking as part of a group and collectively establishing a shared body of knowledge to inform what you will do, the work of your head

DIRECT—acting on that shared knowledge in ways that are negotiated by all, the work of your hands (Sand Talk, 2019:275).

![Call of the Dakini | A Memoir of a Life Lived [Extract]](https://regenesis.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Catalogue-OF-Articles-by-Barbara-Lepani-July-2018-July-2023-.jpg)

Recent Comments