Barbara Lepani:

I recently met Ian Milliss who is one of the founders of the Kandos School of Cultural Adaptation (www.ksca.land). I was struck by a piece of writing Ian had on his wall, titled ‘Love among the Ruins’. For me this was the perfect response to the revisioning of our relationship to the natural world and one another as we begin to confront the reality of the impact of global warming and related species extinctions and environmental degradation on both human habitats and all the lifeforms that have been our companions during the years of the Holocene. This geological age has produced the planetary environment that supported the rise of ‘Human Civilisation’ that began over 12,000 years ago after the last glacial age of the Pleistocene. Aboriginal habitation in Australia dates back at least 60,000 years well into the Pleistocene, holding in their cultural memory what it is to live in a world that is less environmentally benign for humans.Grief

As the Extinction Rebellion movement seeks to highlight, human society faces the very real prospect of extinction along with all the other species we have been driving into extinction through our industrial and agricultural practices to pursue our insatiable demand for consumer goods and consumable experiences, like mass tourism. Elisabeth Kubler-Ross mapped out the stages of grief that come with the death of a loved one. For us now grief is for Planet Earth and our consumerist lifestyles. First there is denial, then there is anger, then bargaining and depression, and finally acceptance.

However these stages of grief are culturally informed by how we treat death in the first place. In the modern technologically advanced West, death is an enemy that can be defeated by technology, life can be prolonged, perhaps even forever through cyro technologies. The destruction of Earth as a habitat for humanity can be defeated by technology—the escape to colonies on Mars and/or geoengineering the climate and plant life.

This modern cultural assumption of a ‘tech fix’ feeds on denial and anger—the denial that climate change means we have to change our wants and habits of consumption, that the age of the rule of the ‘White Man’ is over, that ‘America’ cannot be ‘Great Again’. But as this denial becomes harder and harder to sustain, there is the rage that currently feeds into white male victimhood at loss of privilege, the rise of right wing populism for an authoritarian leader who can turn the clock back, the search for someone to blame—the ‘other’—be they Infidels, Muslims, Blacks, Secularists, Experts.

And this bleeds into the epidemic of anxiety and depression, especially among our young.Love Among the Ruins

Sunflowers & Song concert in the canefields, part of Sugar Vs Reef by KSCA members Lucas Ihlein and Kim Williams 2017

For the rest of us we are dealing with bargaining, depression and acceptance. We are looking for ways to respond to the challenge of climate change through transitions to renewable energy, to regenerative farming, to local food production and consumption, to recycling waste, to the coming together of community that welcomes the stranger, the refugee. We are searching to understand how the very way we make sense of our world has led us to this conundrum of an endgame. We are looking into other cultural pathways, like those of Australia’s First Nations peoples with their enduring spiritual connection to ‘country’ that has seen them survive over 200 years of colonial dispossession, cultural and psychic destruction. Where the songlines that criss-cross Australia tell the story of ecological relationships on both a practical level of plant and animal life, and on the spiritual plane of the Creation Ancestors and their totemic expressions.

We are seeking to find and celebrate love among the ruins as we look clear eyed into the future our society is bequeathing to our children and grandchildren. How does the project of art as cultural innovation feature in this? Artists are caught between producing works for the art market and art as cultural innovation that has sought engagement with the community around major contemporary issues.Ian Milliss:

Love among the ruins may well be the most optimistic vision of the future that we could have, a love of all life and its amazing ecological weave, where there is no outside, no autonomy, everything is linked. It is inevitable that any human culture will generate constant cultural change as a type of adaptive evolutionary process. If we were to survive it would be by constantly adapting the cultural memes that make human society work and the people who do that are the people who should be described as artists. Sustainability isn’t even an issue here because it is as natural as eating, breathing, sex. It will continue as long as humans continue.”Barbara Lepani:

Today the most important contemporary issues facing Australian society cluster around:

- Climate—society’s responsibility for global warming and environmental destruction arising from ‘economic growth’ under global neo-liberalism, and our response to this in the fields of energy policy, agricultural practices, mining, transport, industrial production and community cultural adaptation

- Multiculturalism—as a defining sense of Australian identity that incorporates the 60,000+ history of our Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander First Nations peoples, the stories of dispossession and early European colonial settlement and establishment of Australia as a ‘Christian Anglosphere’ under the White Australia Policy, and the post war challenge of incorporating new immigrant arrivals—first the Greeks and Italians, then the Vietnamese and Chinese and more recently people from South Asia, the Middle East and Africa—creating a multi-faith, multi-ethnic Australia

- Gender—incorporating issues of gender equity between men and women in economic, social and political participation, tackling family violence that sees one woman murdered every week, grappling with gender fluidity among the LGBTQ community, and the resulting redefining of what it means to be a ‘man’ or ‘woman’ in our society

- Globalisation—facilitated by information and transport technologies that has created a world order of the increasing concentration of wealth and political influence in global oligopolies in the technology, pharmaceutical and resources sectors that are bleeding revenues from the ability of nation states to ‘civilise capitalism’ by redistributing wealth via taxation to fund essential social services, infrastructure and social payments to those actively disadvantaged by the forces of capitalist economic production

- Security—incorporating issues of the militarisation of societies through the armaments industries transformed by advanced technologies (AI and biotech), technological surveillance of populations such as China’s social credit system, the intrusive nature and psychological impacts of social media, and the rise of information ‘warfare’ by nation states, corporations and criminal syndicates.

Since Ian began exhibiting artworks at the age of 16, he has been on a mission to celebrate the artist as shape shifter through direct engagement with social and political issues. This led him into the world of conceptual art as a reaction to the growth of the international art market, where under the politics and practice of the globalising neo-liberal economics, art has become a collectible ‘asset class’ for high end investors and ‘home décor’, and artists, as small business practitioners, need to produce saleable works for the ‘art market’.Ian Milliss:

- In the mid 1970s the fall out from conceptualism split art into two competing practices. The conservatives became the manufacturers and distributors of commodity art and the radicals became integrated with community activism until they simply dissolved into day to day life, the energy of the individuals going into a whole range of culturally innovative activities that are rarely if ever described as art.

- As the art world has perfected itself as a business model it has destroyed itself as a site of cultural innovation, the real business of artists. Unfortunately if the conventional art world is not where cultural innovation is happening then it is no longer significant except as a sociological phenomenon. The neoliberal undermining of government support for the arts since the 1970s has imposed sponsorship and benefactors on institutions that were previously adequately publicly funded. The conversion of art into just consumerism has converted cultural workers into just workers. Artists can no longer rely on teaching, for instance, nor are there now other reasonably well paid flexible forms of work. Casualisation and the repression of the union movement have destroyed that.

- As always there is the opiate of the possibility of a brief flash of fashionability, a prize win, a small grant, but these are basically delusions to keep the peon artists supplying cheap exhibition fodder for the institutions and the market. The real money goes to the already rich speculator collectors who are usually buying in the secondary art market, of no benefit to the original producer.

- By 2019 we are witnessing how the official art industry is being undermined by the growth of the internet and ubiquitous media which has turned the art into life credo of radical conceptualism into a normal facet of life. The organisations of the art world are increasingly mostly involved in one aspect or another of sales, marketing or promotion, of cultural product. These are exactly the functions being fatally disrupted by the internet with its easy and virtually free access to global audiences and support for a wide range of media.

- A large portion of the population now generates their own visual culture on a daily basis and distributes it via youtube, facebook, instagram. This is the final formation of the provisional wing of conceptualism, the radical urge to blend art back into daily life. Although it too is implicated in the neoliberal project it is also more deeply rooted in widespread human creativity, more about play, less about profit.

- Ironically the neoliberal commodification of art has produced a situation where those who manufacture official art are not cultural innovators and so are mostly not artists, whereas those who generate their own content mostly don’t make official art but are artists by virtue of being cultural innovators.

Art as Cultural Innovation

Barbara Lepani:

Ian Milliss’s ruminations bring us back to the role of artists as shape shifters, as cultural innovators, as seers through the shifting veils of how reality streams into our awareness. Ian poses these questions for discussion.Ian Milliss:

- If we start talking about all human activity as the soil that must be sifted for the nuggets of art it becomes easier to recognise that the people who should be called artists are those who are most successful at developing our understanding of reality, no matter what media they use to do it.

- This changes the nature of any discussion of art into a discussion of cultural memes, innovation and significance in any and every human activity. Most of the people who have been calling themselves artists can now be seen as small businesses manufacturing decoration or entertainment products, often highly creative but conforming to well known patterns. The result is an enormous industry producing stuff that looks like art once looked but without much cultural significance beyond the fact that its existence shows how evolutionary processes can be hijacked by parasitic memes.

- Treating art as simply a descriptive term describing depth of innovation in all human activities may destroy the mystique of official art but is a sustainability lifeline for the concept of art. Art as cultural memetic innovation is no longer a form of consumerism and it requires almost no resources, guaranteeing its sustainability into the medium term, the final stages of social collapse.

- The collapse of global industrial civilisation is not even the worst-case scenario. There is also the likelihood of near-term extinction (NTE). We are in a situation where one of our cultural memes, neoliberalism, is waging war on all the life on the planet and the planet is losing. We have entered the Anthropocene Age where humans are actually in control of the future of life on the planet without excuse or backup. There is a deep reluctance to face this fact. At a conference called 21st century Artist that I spoke at last year only myself and one other speaker out of about forty made climate change the heart of our speech. It’s not as if artists have no role in preparing us for our own extinction, you can already see that happening in Lars Von Trier’s film Melancholia for instance.

- We would not be the first human society to fail, as Browning’s arcadian poem noted, but we would be the first to take a large part of planetary life with us. And it is just possible that small remnants will remain, in fact perhaps a small hi tech society will survive that has learned once and for all the lesson of the Anthropocene, that if we are now in control of nature then we must behave with absolute responsibility.

Intersubjectivity and Eco-Consciousness

Barbara Lepani:

And finally a word from environmental philosopher, Freya Mathews (www.freyamathews.net)

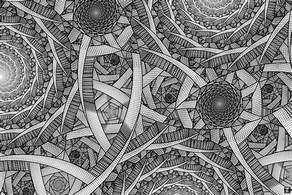

“When we experience reality, Escher-style, as a field of internal relations, everything fitting together, the identities of things porous and inter-permeating, everything fluidly pouring into and out of everything else, no rigid boundaries or hard edges, no intractable resistances, everything responsively seeking a space for itself in the moving jigsaw of others, then the world of outer sense has the same quality as the inner field of consciousness, in which thought and experience inter-morph and inter-permeate, resolve and dissolve, in just this fluid kind of way. The world of outer sense, in other words, has a character consistent with its being the outer expression of an inner field of subjectivity.”

From: Chapter 18:13 “Why has the West Failed to Embrace Panpsychism”? in David Skrbina (ed), Mind That Abides: Panpsychism in the New Millennium, Advances in Consciousness Research Series, John Benjamins, Amsterdam and Philadelphia, 2009 pp 341-260

![Call of the Dakini | A Memoir of a Life Lived [Extract]](https://regenesis.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Catalogue-OF-Articles-by-Barbara-Lepani-July-2018-July-2023-.jpg)

Recent Comments