References

This post draws on two sources—both have profound insights for how the arts might respond to the core challenges of our times:

- Climate change and environmental destruction of Planet Earth through the cult of ‘economic growth’

- Responding to Australia’s contested history and the Uluru Statement from the Heart

- Escaping the prison of only Western (whitefella) ways of knowing and making sense of reality and our relationship with the living world.

Rachael Swain, Dance in Contested Land: New Intercultural Dramaturgies, 2020

Rachael Swain, Helen Gilbert, Dalisa Pigram (editors), Marrugeku, Telling That Story—25 Years of Trans-Indigenous and Intercultural Performance, 2020

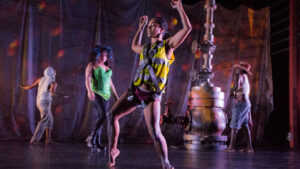

Cut the Sky—Five Songs for the Future

This performance work by Marrugeku was listed as a meditation on humanity’s frailty in the face of our own actions. In a burnt landscape, a group of climate change refugees face yet another extreme weather event. Propelled back and forward in time, they revisit conflict with mining companies, the destruction of fauna and relegation of the marginalised, while contemplating the gift of human life and the life-giving force of the sun. Crocodiles who once were human lurch at each other’s throats, butterflies swarm searching for water, dancers disintegrate into the light, a song is sung for the rain.

Dalisa Pigram and Rachael Swain, the Artistic Directors of Marrugeku say that In creating Cut the Sky, they wanted to give form to ways of knowing and doing and being that exist in Indigenous knowledge systems and approaches to ‘caring for Country’. They sought to offer their audiences the chance to consider climate change through another lens, exemplified in the poetry of Walmajarri/Nyikina artist, Edwin Lee Mulligan, the songs written specially for the production by Ngaiire (in English) and Eric Avery (sung in Ngiyampaa Wangaapuwan) and the restless and urgent choreography of the dancers. The performance of Cut the Sky was organised in five acts that speaks to this ontology:

Act 1. Disaster

Act 2. Deeply Cut Wounds

Act 3. The Sun

Act 4. History Repeats

Act 5. Dreaming the Future

Mythopoetic Ways of Knowing

Cut the Sky works at the interface between modernity and the First Nations’ world of knowing that is encapsulated inadequately in the English word ‘the Dreaming’, as well as across all times—past, present and future. It was originally coined in the late 19th century by amateur ethnologist, Francis Gillen as a translation of the Arrernte term ‘Alcheringa’. The anthropologist, William Stanner (‘The Great Australian Silence”, Boyer Lectures 1968) argues: “We [non-Indigenous Australians] shall not understand The Dreaming fully except as a complex of meanings”. The different language groups in Australia all have their own name for this complex. In Yawaru culture is is known as Bugarrigarra, in Kunwinjku as Djang, in Central Desert cultures as Jukuurpa. In their cultural management plan, the Yawaru explain that:

Bugarrigarra signifies a non-ordinary reality, not mere insubstantial phenomena. Bugarrigarra is a world creating epoch and the supernatural beings active in that time. These beings are responsible not only for the formation of the world and its contents but also for the introduction of social laws and principles governing human existence. Bugarrigarra is also credited with the introduction of human languages, the seasons and their cycles, the nature of our topography and the biodiversity.

Mytho-poetic ways of knowing and describing ‘reality’ are common in pre-industrial cultures, particularly those who experience the natural world as animated with spiritual presence. It is a way of knowing that has largely been lost in modern cultures, but which we seek through the arts, in works like Cut the Sky, and in story telling that takes a mythic form, charged with metaphor and non-rational modes of experience. What is particularly significant is that it cuts through the modern experience of alienation and aloneness that comes with modernity’s extreme individualism, to create an inner experience of what the Buddhist Vietnamese teacher, Thich Nhat Hanh called, ‘interbeing’—the actual experience of feeling one is part of the natural world including other human beings, rather than apart from them.

An example of the mytho-poetic way of thinking is shown in Cut the Sky, in the treatment of gas as ‘Dangkapa’ (Poison Woman), a new source of wealth in the modern Australian economy but the extraction of which has major implications for Caring for Country. In north-west Australia, cultural relationships and responsibilities are being challenged by large scale mining projects. In a key moment in Cut the Sky, Edwin tells the Dreaming story for the gas, as he says, ‘the most desired mineral right now in the Kimberleys’. She is buried deep in his spirit Country. In his fourth poem, ‘Dangkaba’ (Poison Woman), he explains for the audience her presence. She exists at the same time as a mineral and as a dangerous and lusty woman who can cause death, and yet she is a custodian who cares for her Country. On the set of Cut the Sky, Dangkaba appears as the looming presence of the gas well-head.

Dangkaba, on the set, can be found in a physical site near Noonkanbah. Edwin’s poem and the figures who re-emerge across time in Cut the Sky – Indigenous and non-Indigenous mining workers, a geologist, a sex worker, a displaced traditional owner and a protester – give form to political issues as they have played out in the Kimberley from the late 1970s, inspiring our speculative vision of life 100 years into the future.

As Rachael Swain makes clear in her book, ‘Dance in Contested Land’ (2020), the implications of this ontology is that land, atmospheres, minerals, waters, the living and the dead, non-human species and Ancestral forces all have presence and agency and are responsive and responding to human lifeworlds. Swain discusses how there is much work to be done by those of us of settler descent to widen the space for the reception of Indigenous arts practices and for the implications of this to contribute to mediating histories, lived experience and imaginations in wider global arts communities. This book seeks to demonstrate by example respectful practices of engaging in nation-specific intelligence through direct discussion and collaboration with Indigenous custodians on their own land.

Listening to Country

Cut the Sky was born of a desire to interrogate Marrukegu’s practice of listening to Country in a time when the lands of many language groups in the Kimberley region are being industrialised, and to workshop the implications of this for dance and dramaturgy that address global climate change. Swain: “We worked with Mick Dodson’s description of the meaning of Country: For us, Country is a word for all the values, places, resources, stories, and cultural obligations associated with that area and its features. It describes the entirety of our Ancestral domains.”

As Patrick Dodson, a senior cultural dramaturg for the work explained:

We are a damaged restoring imperfect society. We have to deal with ourselves. In the meantime, we have this tsunami coming towards us. We are dealing with the full frontal assault of the Western world’s might. It’s imbalanced. There is no song or story for that. Bugarrigarra (creation time that is ever present) has to guide us through.

Dramaturg consultant, Hildegard de Vuyst comments: “I think any work of art is only partially knowable to its creators. There are always parts that escape ‘knowing’. When we talk about intercultural dramaturgy, it’s about including other forms of knowledge, of understanding time and place, of reading he world and shaping our future, which should be a future together. It is how to create forms and perspectives for he future with people who don’t share a common past.”

Challenging the Construction of Time

In modern Western culture time is primarily experienced in a linear way – past, present, future—and yet nightly in our dreams our minds play havoc with this clear organisation of events and experience, pointing to the way our actual experience of time is not this clear one way arrow of time. And once we tune into the seasons of natural ecologies, we experience time as circular—daily, monthly and yearly; all marked by the behaviour of plants, animals, birds, the elements and the night sky.

Swain talks about how, as Marrugeku created Cut the Sky, they sought to both invert the concepts (from the effects of listening to and the effects of not listening) and also, in a radical dramaturgical moment, totally reverse the order of the scenes. The cyclone doesn’t loom and pass, but Cut the Sky begins in the midst, sometimes in the near future, contemplating the increase in extreme weather events.

They explain how the shifting of time and of cause and effect has been in part an attempt to come to grips with the sprawling nature of climate change – and with who or what is in control as the work asks: ‘How do we value what is above and below the earth’s crust?” Swain explains how “there is a sense that the cyclone has been circling us as we work. That it, in turn, has been listening to us discuss what new stories we need to guide us through, causing us to dance at the edge of the apocalypse.”

As Hildegard de Vuyst, Dramaturg consultant on Cut the Sky, who is the resident dramaturg of Belgium’s famous contemporary dance theatre company, les ballets C de la B, explained: Cut the Sky is based on collage by juxtaposition in time. But in that juxtaposition, we eliminated to the maximum cause and effect, or past and present logic. Basically we took out the narrative and replaced it with poetic logic, jumping between times (present, past, present, future, past, etc) and perspectives: for example, drone images versus kangaroo versus humans. In that sense it was freed from a normative Western dramaturgy. I think of it as a payer or an entreaty by a temporary community of people.

Swain: “In the face of the social, cultural and environmental implications of climate change, the philosophical binaries of nature versus culture and the scientific separation of humanity, on the one hand, and ecology on the other, are in the process of dissolving. The challenges and possibilities enfolded within this conceptual shift stood behind our research and performance making processes. Dodson highlighted for us that a central premise defining Cut the Sky is that for many First Peoples, dystopian pasts and presents reverberate within dystopian futures. This premise fundamentally informed the work’s multi-temporal structure.”

Swain explains that one of the things that Cut the Sky attempted to do was to make time visible from the perspective of Aboriginal ways of knowing Country. Instead of a linear approach to time, place becomes the horizon of temporality, so a Dreaming figure like Dangkaba can be present in multiple places and at multiple times simultaneously.

![Call of the Dakini | A Memoir of a Life Lived [Extract]](https://regenesis.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Catalogue-OF-Articles-by-Barbara-Lepani-July-2018-July-2023-.jpg)

Recent Comments