Cancer

One of the most pernicious diseases to afflict the human population is cancer, when the body produces cells that multiple and destroy it. Likewise the impact of the human dream of Progress as continuous economic growth and improved living standards through technological innovation and productivity (more with less) has translated into a ‘cancer’ that is threatening the viability of human life on Earth.

Thinking about cancer we can readily see how this is an apt metaphor for the way in which human communities have grown and multiplied, but have formed abnormal/mutant cell clusters that have then metastasised to eventually strangle the conditions for healthy human communities in relationship with the wider body of Planet Earth.

Mestastasis

Cancer is a disease of the body’s cells. Normally cells grow and multiply in a controlled way, however, sometimes cells become abnormal and keep growing. Abnormal cells can form a mass called a tumour. Cancer is the term used to describe collections of these cells, growing and potentially spreading within the body. As cancerous cells can arise from almost any type of tissue cell, cancer actually refers to about 100 different diseases.

As mutant cells (those with mistakes in their genetic blueprint) grow and divide, a mass of abnormal cells, or a tumour, is formed and can travel via the bloodstream or lymphatic system to different parts of the body. These cells can settle in other parts of the body to form a secondary cancer or metastasis leading to death.

Tumours of Modern Civilisation

What are the ‘tumours’ of modern civilisation that are threatening human societies:

- Global warming from carbon emission from the use of fossil fuels for energy, fuel and heating

- Loss of biodiversity through species extinctions as a result of land clearing

- Ocean acidification and loss of seaweed forests

- Bleaching of coral reefs

- Desertification and loss of fresh water resources

- Socio-political armed conflict and ethnic tensions within and between nation states

- Pernicious impact of social media on human psychology and community – narcissism, hate speech, body dysmorphia, consumerism

- Extractivist logic driving economic systems leading to extreme wealth inequality and resulting social tensions and human impoverishment

Two decades ago, scientists thought it would take a rise in global average surface temperature of 5°C above pre-industrial levels to reach climate tipping points. Recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reports suggesting this could occur between 1°C and 2°C. The World has already passed 1 degree warming. Even if countries implement their current pledges to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions, we are likely to see at least 3°C, despite the Paris agreement to keep warming well below 2°C.

The Unravelling of Extractivism

We all acknowledge that the death of Queen Elizabeth II signals the end of an era—from Britain’s Imperial Glory to the British Commonwealth and the triumph of the Anglosphere in the American Century, global dominance by the Anglosphere is coming to an end. Wth the rise of China and India as major powers a new World Order is slowly being crafted.

Although the US remains the world’s richest country and biggest economy, it is facing very serious political challenges. While global capitalism, dominated by US tech and fossil fuel giants has delivered great wealth to a minority of the population, it has devoured the middle class on which democracy rests for its viability, and has plunged many into absolute poverty and homelessness. The populist MAGA Trump-led presidency as a solution to this, to ‘Make America Great Again’, only served to prove that transactional capitalism combined with jingoistic nationalism has further entrenched the unravelling of the US dream of Progress and Wealth for all.

Not only is the world facing a climate crises, it is facing a crises of displaced persons and refugees, which in turn is leading to ethnic nativism in many nation states of Europe, and even immigrant nation states such as the United States. Across Europe, the so-called home of liberalism, we are seeing the rise of far right populism, which is characterise by hostility to “elites”, authoritarian tendencies, disdain for multiculturalism and gender rights and an obsession with national identity underpinned by racism. Given the significant non-European immigrant and refugee communities now living in Europe, and the rise of displaced people in Africa, the Middle East and Asia, such political trends are likely to intensify.

As my mind dwelled on this, I realised that combined with ideas buried in Greek Philosophy and the veneration of mind versus nature, Western culture became captive to what we might now consider an ‘ontological’ cancer. One of the roots of this cancer lies in the Old Testament, GENESIS V.1.26, which declared that God made ‘man’ in his image, and gave ‘him’ dominion over the Earth and all its lifeforms. Only man had a soul/mind—everything else was brute nature. This not only set up the triumph of patriarchy and all that has meant for the oppression and exploitation of women and their wisdom, but also a fundamental alienation from the natural world. The claim that dominion was a call for ‘wise stewardship’ still leaves the fundamental alienation in place – of human exceptionalism separate from and parent over the rest of the natural world. The sort of hubris that has also underpinned patriarchy’s denial of female autonomy and agency, anchored as women are in the ‘messy’ business of biological reproduction.

This ‘ontological cancer’ began to metastasise when it was followed by the mechanistic materialism of the scientific revolution and the industrial revolution that followed, leading to an accelerating pace of technological innovation. This spread throughout the world through European imperialism, searching for hegemonic dominance through the era of global capitalism and its ‘New World Order’ of free markets and ‘nation states’ and various forms of political organisation such as democracies, oligarchies and autocracies. It now threatens the global body politic.

Failure to Cure the Cancer of Extractivism

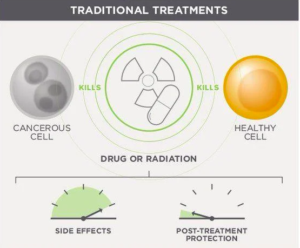

Aboriginal Elder, Dr Mary Graham has identified that the basic logic of modern Western (now global) culture is extractivism – that wealth has been gained by extracting it from nature and from human labour. However just as seeking to cure cancer through the traditional approach of a ‘war’ on cancer through surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy had mixed results, frequently causing yet more danger to the whole, seeking to cure the ontological cancer of our misguided view of our human place in the world, with small add-on changes, such as a move from fossil fuels to renewable energy, is unlikely to succeed. Because it flies in the face of the actual nature of total systems reality.

If we try to tackle the climate crises and its offshoots with a ‘technology-fix’ still rooted in the old paradigm of extractivism and continuous consumer-based economic growth based on consumption-economics, we are still trying to cure the ‘cancer’ of Modernity with traditional means?

Whatever good intentions inform reformist public policy, the overall paradigm still rests on extractivist logic—the gaining of wealth by extracting it from nature (mining, agriculture, fishing, factory farming) or from human labour (slavery, wage theft, human trafficking, union-busting).

This extractivist view of reality continues to inform our technological entrancement with bio-engineering and AI promising to deliver us ever increasing material standards of living, including space tourism and immortality though a transition to a cyber-humanity.

However the threat posed by the climate and ecological crises that is the result of this long trajectory of belief in human progress through economic growth and technological mastery over nature is marked by a growing incidence of iatrogenic impacts, which we now call wicked problems.

Is making Australia a ‘renewable energy super power’, without challenging the underlying extractivist paradigm, doomed to create unintended iatrogenic effects on the whole system? Is this just another example of the dangers of Gregory Bateson’s idea of mere purposive consciousness that fails to ‘see’ from a viewpoint of total ecological systems awareness, wisdom?

Technological Entrancement

The height of technological entrancement can be seen in Saudi Arabia – where the desert Kingdom has ridden the oil bonanza in partnership with the USA to create a nation of fabulous wealth for the few resting on with massive exploitation of foreign fellow Islamic workers and the oppression of women, now engaging in futures fantasising in a post fossil fuel age. We move from Dubai as today’s wealth extravaganza to the vision of NEOM, the AUS$745 billion project envisaged by MBS, Mohammed bin Salman, the 36-year-old crown prince of Saudi Arabia.

A plaything for futures oriented architects and Hollywood set designers, MBS wants it to be a showpiece that will transform Saudi Arabia’s economy in a renewable energy world shaped by AI, and serve as a testbed for technologies that could revolutionise daily life.

In reality it seems more like this promised future is a veneer, a layer of technological gloss over a core of repression, kleptocracy, and—above all—indefinite one-man rule. This sort of technological entrancement is the plaything of the mega-rich, where the lessons taken from the film Blade Runner are not the plight of the masses or the AI humanised cyborgs, but the rich who float above them.

The chosen site in Saudi Arabia’s far northwest, stretching from the sun-scorched Red Sea coast into craggy mountain badlands, has summer temperatures over 50C and almost no fresh water.

Curing the Cancer of Extractivism

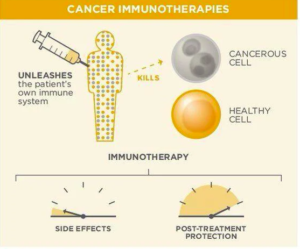

To return to our cancer metaphor, do recent developments in immunotherapy to treat cancer offer us a way to imagine a way of combining the best of Western science with the ancient wisdom of total ecological systems awareness that underpins First Nations knowledge systems?

As science increasingly looks to biology for answers, can it overcome its institutional structure of narrow specialisation and instead embed these within a framework of total ecological systems awareness?

Using cancer as a metaphor, let us imagine that each cell is a local socio-economic system/community that is based on relationist logic.

As part of its normal function, the immune system detects and destroys abnormal cells and most likely prevents or curbs the growth of many cancers. For instance, immune cells are sometimes found in and around tumours. These cells, called tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes or TILs, are a sign that the immune system is responding to the tumour.

In our metaphor, the TILs are the pioneers of developing a regenerative framework for future socio-economic development and governance systems.

REGENESIS Through Relationist Logic

Because First Nations knowledge systems are based on an understanding of how to live WITH nature as an intrinsic part of the whole eco-system that describes life on Earth, they are based on the idea of an immutable LAW. This was passed down from the Ancestral Beings and held in sacred trust by the Elders, who were introduced to this knowledge through immersive and transformative ceremony in a series of stages that ensured their spiritual maturity. Such knowledge was not open to everyone, as is the custom of Western knowledge systems, which carry no intrinsic moral responsibility. Instead the wisdom eco-systems knowledge of the ancestors, encoded in the songlines, taught not only how to live on Country, but how to look after Country in all its multiple dimensions. This knowledge was only passed to those regarded as suitable vessels—those of a pure heart without malice or self importance. The Aboriginal TV series, ‘Cleverman’ 2016-2017, created by Ryan Griffen based on an original idea by Jon Bell and Jonathan Gavin, is a portrayal of this principle.

Traditionally very strict rules of secrecy governed First Nations ceremony practices as a way of passing on this sacred knowledge. When I was working with Yankunytjatjara man, Uncle Bob Randall, on his autobiography in 1999, published as Songman (2003), I asked him the purpose of such strong rules of secrecy; punishment of breaking this secrecy could be harsh, such as spearing in the leg, or even death. Bob explained: “That knowledge is not something you gossip about to those who have not undergone ceremony. It is something that you hold deep inside you; it is meant to transform your very being.”

I also remember Bob telling me that we have to learn from the spider. When he/she builds their web, they can tell by the vibrations of the web what they have to pay attention to. Is it food that will nourish them, or is it danger, which it must repel? He said we need to be like this, able to sense from the vibrations in our environment what is good for us and what we should avoid. Bob pointed out to me that when ‘whitfella’ government come to talk with his people, they send the young ones out to talk to them, while the elders sit in the background, communicating with the silent hand gestures of the hunter as to whether to listen to this one because they spoke ‘true’ or whether to ignore that one because they spoke ‘humbug—without integrity and full of guile.

I’m a spiritual practitioner in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition where this wisdom tradition involves its own sort of ceremony involving tantric vows, use of mantra and visualisation practices, along with deep and sustained meditation. In this tradition I also took a vow of secrecy and a commitment to hold a sacred relationship with my teacher who transmitted this knowledge to me. I recognised the purpose of ‘not talking about it’ was the same—to transform my very being and way of experiencing reality, beyond the culturally conditioned view of my ordinary conceptual mind.

Within the constraints of men’s business and women’s business that defines Aboriginal knowledge systems, Bob and I spent a lot of time exploring similarities and differences between his knowledge system and the Buddhist one with which I was somewhat familiar, although still very much a student.

Later on, between 2006 and 2009 I undertook a three-year retreat in the Tibetan Nyingma tradition, which involved extensive study and prolonged periods of isolation in meditation using tantric visualisation and mantra practice. This involves vows of secrecy for the purpose is experiential realisation, not knowledge about, or the mere counting of mantra accumulations and time spent in retreat. In fact, when people asked me how the retreat changed me, I have found it impossible to put this into words, and yet it is something I can share silently with others who have undertaken similar practices—a sort of liminal knowing that needs no words.

In this tradition, the signs of accomplishment are not measured by the amount of time you spend in the practice of meditation, but how you deal with life in the post-meditation state—how you meet life’s challenges; how you are able to flow with life’s impermanence; how you have softened your tendencies to fall into habitual patterns of aggression, greed, self importance and indifference. As the Australian Buddhist nun, Robina Courtin says: “In Buddhism we say a bird needs two wings, wisdom and compassion. Wisdom is the internal, putting yourself together. Compassion is when you put your money where your mouth is and help the world.”

Dadirri—inner deep listening and quiet still awareness

The greatest challenge that we children of Modernity face is how to recapture a sense of the world as thoroughly animated, where the land, trees, plants, water, wind, birds, insects and animals all have their own voice and speak in their own language. To be able to listen to this voice we need to quieten the chatter of our ordinary conceptual mind with all its worries, dreams and fantasies, and enter into a meditative state of quiet, still, deep listening through our feeling sense, our intuitive mind.

The Elder, Miriam Rose Ungunmerr-Baumann, a Ngangikurungkurr woman of the Daly River, calls this practice ‘dadirri”—which translates as inner deep listening and quiet still awareness. She considers this the greatest gift that her people can give their fellow Australians. Like many Aboriginal people, Aunty Miriam has embraced Christianity but in the process she has thoroughly indigenised it. God is not the super human patriarch, but creation itself, which is held sacred. In a similar fashion, Aboriginal funeral services are a rich blend of Christianity and ancient Aboriginal customs. They are quite elaborate affairs allowing for strong emotional mourning as the threads of community are rewoven, following the departure of one of their own from their community of connection.

In a world of relationist logic, relationship is everything, while at the same time is makes room for personal agency and autonomy.

Caring for Ngurra (Country)

To Care for Country does not simply involve adding ‘cultural burning’ to the tools of modern bushfire management, or even regenerating damaged bushland and rescuing wild animals. It involves a complete re-framing of one’s relationship with Country as a spiritually charged world where the landscape pulsates with a vibratory presence—the continued vitality and fecundity of the creation ancestral beings who are past and every present, defying the construct of linear time that defines modern Western culture.

Despite the systematic epistemic violence of colonisation that denied the legitimacy and validity of their ancient knowledge systems and which deliberately sought to extinguish their languages, subjecting them to continued institutional violence as evidenced in their high rate of imprisonment in the Australian criminal justice system, Aboriginal people never abandoned their intimate eco-spiritual understanding of their timeless and unbroken relationship with Country.

As is acknowledged in the Blue Mountains City Council commitment pledge to the Gundungurra and Dharug people of the Blue Mountains, despite massive adversity, their story is one of heroic enduring resistance, survival, reawakening and reclamation of their rich cultural inheritance. This is the journey being sought by the Uluru Statement from the Heart and the call for Voice, Treaty and Truth as a gift to all Australians. It is why the Referendum on the Voice is the most significant moment in our history since First Nations people were included in the Australian nation as citizens, back in 1967.

Those of us from the settler immigrant population—the earlier British and Irish settlers, whether convict, free settler or prison guard, and those who came after the gold rushes and the European wars—those of shared European cultural background, we have a special responsibility as we comprise over 75% of the total Australian population, and it is our culture’s institutions that shape our governance, economy and education systems. The more recent immigrants and refugees from the Middle East, South East Asia, China, India, Africa and the Pacifika from our Pacific Island neighbours, together comprise another 22%, while our First Nations people are only 3% of Australia’s population.

However it is this 3% that carry the weight of helping the rest of us reimagine our relationship to the natural world and free ourselves from the chains of extractivism and alienation from the natural world, to embrace the relationist logic of First Nations knowledge systems. This is the journey we must make.

Learning from the Elders

All over Australia, First Nations Elders have been trying to help us to wake up, despite our arrogance and assumptions about the technological triumph of ‘white’ civilisation and all the material benefits it has brought to human civilisation. We have organisations like Regenerative Songlines Australia and Future Dreaming – and many, many others, along with the extraordinary outpouring of creative works through film, visual art, music and creative writing. This is the foundation of our identity as a multicultural nation marrying the ancient with the new.

The year I spent working with Uncle Bob Randall after he asked me to help him work on the manuscript of his autobiography for which he received an Australian Council for the Arts grant, was an incredible gift. I met Uncle Bob when I was researching the idea of wisdom and eldership in different religious/sspiritual traditions, beginning with Aboriginal culture. Tucked into the rainforest at Stanwell Park where I was living at the time, we yarned away; I listened to Bob’s haunting music, especially his ‘My Brown Skin Baby’; I read and researched, and I worked with the text. Towards the end of 1999 we went on a long road trip back to Uncle Bob’s country. As a Yankunytjatjara man, Uncle Bob’s birthright connections were to the people of the Mutitjulu community of Uluru.

He was born at Tempe Downs – his father, Bob Liddle, was a European cattle station owner, his mother a member of a group of Aboriginal people camped on their own country, now ‘owned’ by Liddle. As a result, being lighter skinned Bob was taken away by police to the mission at Alice Springs, where all record of his birth mother and connection to Country was erased. He was then shipped off to grow up on the Anglican mission on Croker Island, off the coast of Arnhem Land On this journey we visited Uluru and Uncle Bob took me around to the sacred spring of the Rainbow Serpent, shared the many stories of the sacred place with me. We went digging for honey ants and ate the rich nutty witchety grubs. We also camped at Tempe Downs before returning to Alice, and then onwards to the north through Kakadu National Park to Ainslee Point—across from Croker Island.

Like many Aboriginal people, Uncle Bob Randall worked tirelessly as a translator between Indigenous culture and the white settler culture that governs our institutions of governance, business and education. He did this work at various universities and in Central Australia, helping non-Indigenous people who came there to work with Aboriginal organisations in health, legal aid, media and the arts. I remember a piece of advice Bob gave to my friend Graham, as we were travelling with him through his country in Central Australia. My friend was worried that he had never been able to form an intimate relationship with a woman, to find true love. Uncle Bob said, “Well, we’ve got love magic for that. It’s simple. Learn from the bees. Become like nectar in your way of being, and the ‘bees’ will come to drink.”

Kanyini

One system that Uncle Bob developed, which he discussed in his book Songman, is Kanyani, based on four interlocking principles:

- Tjuukurpa – LAW of total systems awareness

- Ngurra – belonging with Country

- Kurunpa – love, spirit, soul

- Walytja – family connectedness

In 2006, Uncle Bob co-produced and narrated the award-winning documentary, “Kanyini”. (https://vimeo.com/292549994). Uncle Bob’s wife, Barbara Randall now runs the Kanyini organisation to continue his work (kanyini.org.au)

“Kanyini” was voted “best documentary” at the London Australian Film Festival 2007, winner of the “Inside Film Independent Spirit Award”, and winner of the Discovery Channel Best Documentary Award in 2006. Uncle Bob continued to write and teach throughout the world, presenting teachings based on the Anangu (central desert Aboriginal nation) “Kanyini” principles of caring for the environment and each other with unconditional love and responsibility. His tireless dedication called indigenous people to reclaim their Aboriginal identities and re-gain lives of purpose, so that the relevance of ancient wisdom to modern living is understood.

As explained by the Kanyini organisation, in this way Uncle Bob dedicated his life to being a living bridge between cultures and between world nations, creating lines of understanding so that indigenous and non-indigenous people can live and learn together, heal the past through shared experience in the present, sharing a way of being that allows us, once again, to live in oneness and harmony with each other and all things. Uncle Bob passed away in May 2015, one of the generation of ground breaking First Nations Elders who have left us with the treasurers of their wisdom and generosity such as Charlie Perkins, Eddie Marbo, and most recently Uncle Archie Roach and Uncle Jack Charles. So many… These are the famous ones, but in reality it is the many women Elders who have really held their communities together in the face of the cultural devastation—grog, violence and mental illness the most obvious outward signs— that ‘white’ civilisation has wrought through its denial of First Nations knowledge systems and inability to incorporate its wisdom traditions into institutional arrangements across all the domains of modern society.

![Call of the Dakini | A Memoir of a Life Lived [Extract]](https://regenesis.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Catalogue-OF-Articles-by-Barbara-Lepani-July-2018-July-2023-.jpg)

Recent Comments