The Serpent Gurrangatch and the Hunter Mirragan

The following post is based on a talk that Bhikkhu Sujato gave at “New Horizons in Buddhism”, the 16th Sakyadhita International Conference on Buddhist Women, held at Leura in the Blue Mountains in June 2019.

Global warming is an unprecedented threat to the survival of our civilization and culture, indeed our very lives. The Gundungurra myth of Gurrangatch and Mirragan tells of a time when the land of the Blue Mountains was shaped in the struggle for life, a struggle marked by both passion and restraint. While the future has never been more uncertain, our wisdom traditions offer us ways of talking about and responding to change as conscious individuals able to reflect on and choose our own responses. The wisdom of our indigenous peoples has been disparaged or neglected, and the cost of that neglect is becoming ever clearer as our climate changes and nature is decimated.I am not of the Gundungurra people, and this is not my story. Yet it is my land; not in the sense of ownership, but of belonging and kinship. I will never fully apprehend what it means to be on story with the land, to have my song be the land’s song. I experience the story of Gurrangatch and Mirragan, not while walking the paths they forged in the tale, sheltering under the mountains they built, and drinking from the streams they swam, but via a constellation of interpreters and technologies, removed and abstracted. I cannot tell you what this story meant to the people who lived in this place. I can only say what it means to me, offering their story for you today in a spirit of the deepest respect for the Gundungurra people and their culture. This is a story of the dawn; let us see what it has to say to those of us who live in the twilight.

Gurrangatch & Mirragan—as featured at Jenolan Caves Blue Mountains

Around 1900 an ethnographer and surveyor named R.H. Mathews met with Gundungurra people of the Burragorang Valley and recorded the creation story of the serpent Gurrangatch and the hunter Mirragan; of how their struggle shaped the rivers, hills, and valleys we know today as the Blue Mountains.

Gurrangatch is the eel, the form that the mythic Rainbow Serpent, a central creation force across Aboriginal Australia takes in the lands of the Gundungurra and Darug peoples of the vast Blue Mountains area. It is a symbol important across many cultures, including the naga (Tib: lu), which rose up to guard Prince Siddhartha during his meditation that led to his enlightenment, becoming known as Buddha, the Awakened One. It points to the deepest forces of creative life, the chthonic subterranean world, and in its rainbow form expresses a curious parallel with the entwined form of DNA, the grammar of life itself.In the Gundungurra stories, Gurrangatch is pursued by his protagonist, Mirragan, the quoll known as the tiger cat—cunning, quick on his feet and resourceful, building alliances with the birds to seek to conquer the powers of Gurrangatch.

As recorded by R.H. Mathews, Gurrangatch was half fish and half reptile with shimmering scales of green purple and gold. His eyes shone like two bright stars through the clear green water of his camping ground, where his eyes caught the attention of Mirragan. The landscape of the Gundungurra, from Wollondilly to the Wombeyan and Jenolan caves, and the waterways and water holes of the Jamison were shaped by Mirragan’s relentless efforts to catch Gurrangatch who continuously eluded him.[vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner] [/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner]Deep Myth

[/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner]Deep Myth

As always with deep myth, we can tease out many threads from this story. It is a struggle between cosmic forces, an echo of the fires that shaped the land in geological time. Gurrangatch is an incarnation of the so-called “Rainbow Serpent” who figures in countless Aboriginal creation myths. The dragon or naga mythology, so fundamental to Buddhist story and iconography, draws on the same set of mythic connotations, the formless powerful serpent hiding in the depths of the earth. The suttas speak of a serpent who glides along with fiery breath, manifesting a rainbow of colors.

In the curious mythological Vammika Sutta (MN23), the protagonist must dig, dig, dig and throw away all the odd things their digging reveals. At the bottom of all lies the naga, but this is not be thrown away: it is the enlightened one, and must be honoured and revered. Here, the metaphorical road to enlightenment is not the ascent to higher spiritual realms, but the unearthing of the layers of the unconscious. The naga symbolizes the deepest layer of all—that which is to be retained, not discarded.Mirragan is the closest thing to a human protagonist in the story. He is the ‘tiger cat’ or ‘quoll’, one of the man creatures that inhabit these woods that are neither kangaroos nor koalas. These days quolls are quite rare. Since the white man came, one species has become extinct and all that remain are in decline and under threat.

As a mammal, the quoll is quick on his feet, resourceful. Mirragan’s technology and wiles—poison, spear, club—overmatch Gurrangatch’s primordial strength. He is passionate, proud, and capable, but his obsession brings danger to himself and his kin. Only his wife speaks words of moderation and wisdom. Heroes like Mirragan are remembered because they are so very rare. Far more common are those who get distracted along the way; or those who listen to the begging of the wife, and give up the heroic quest for a smaller, more domestic happiness. In this story, the wife plays the same role as Yasodhara; she is the normal life, the life of contentment for those of us who are not heroes. For every great myth that tells of leaving her behind, there are a thousand tales of the one who gave up the quest, for who could blame them?

But Mirragan’s true skill lies not in his persistence or his cunning, but in forging alliances; sending an unmistakable message of the importance of befriending others and maintaining relationships, it is only after he brings in the birds that he can win. Their attack on Gurrangatch, the birds of the air seeking out the chthonic monster of the deeps, recalls the universal mythic struggle of the phoenix or garuda versus the serpent naga.Conscious Incorporation

In all these motifs, and many more, there are points of interest, lessons to be learned, wisdom to be gleaned.

What does it mean to become one flesh with the monster? It is an acknowledgement that when we reform, we make progress in some ways, but we also unconsciously incorporate the echoes or the dark side of what has been reformed. We imagine that we are better, that we have surmounted and are pure: that is our temptation, our conceit, our precious.

Global warming is all around us and all through us. We incorporate the flesh of change in the air that we breathe, in the water we drink, it is in our own flesh and bones. Look around you: see the mighty, endless forests that have lasted from the days of Mirragan and Gurrangatch. Australia has, still, one of the fastest rates of forest clearance anywhere in the world.[vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1636847772365{margin-top: 5% !important;margin-right: 5% !important;margin-bottom: 5% !important;margin-left: 5% !important;padding-top: 3% !important;padding-right: 3% !important;padding-bottom: 3% !important;padding-left: 3% !important;background-color: #ddac61 !important;}”]A Tibetan Buddhist Perspective—Barbara Lepani

I am close to this story of Mirragan and Gurrangatch. From my house in Katoomba I look down Kedumba River over the Katoomba Falls into the Jamison Valley, the country shaped by the exploits and struggles of Mirragan and Gurrangatch. Close by is a rock formation that one of my Tibetan Buddhist teachers, Wangdrak Rinpoche, identified as a manifestation of Vajravarahi, a Buddhist embodiment of dakini wisdom energy. Being a practitioner of Tibetan Buddhism has taught me how to re-engage from the world of scientific materialism back into the power of mythopoetic thinking into the deep structures of our embodied human psyche.

One of the foundational figures of the Tibetan Vajrayana Buddhism of my spiritual path is Padmasambhava, the tantric mystic from Oddiyana, a small kingdom thought to have been in the Swat Valley on the Silk Road along which the Buddhist teachings travelled from India to China, Korea and Japan. Invited by the 8th century Tibetan King, Trisong Detsen, to come to Tibet to help defeat the negative forces threatening the construction of Tibet’s first monastery at Samyé on the banks of the Tsangpo River, Padmasambhava became known as Guru Rinpoche—Precious Teacher.

His accomplishments as a vidyadhara (wisdom holder) are celebrated in the mythic story of his Eight Manifestations. As Dorjé Drakpo Tsal, he gained power over the nagas and planetary spirits when the Wisdom Dakini, Kumara, cut open her heart to reveal the mandala of the one hundred peaceful and wrathful deities. He then received the empowerments of Amitabha, Avalokitshevaa and Hayagriva when the dakini, Sangwa Yeshe (Guhyajnana) transformed him into the syllable HUM and swallowed him—conferring Amitabha on her lips, Avalokiteshvara in her stomach and Hayagriva in her secret place (uterus) before rebirthing him through her secret ‘lotus’ (vagina).

In the Chöd practice of the Vajrayana, wisdom is gained through mastering one’s fears and compulsion for ego-protection, by practising in ‘charnel grounds’, wild places associated with death (death of the ego) whereby the deceptive view of ego-eternalism is exposed. It is said that to discover the illusory nature of the barren, frightening land is to discover the innermost primordial wisdom (yeshé), beyond hope and fear, the space of all-penetrating limitless compassion.Renunciation

Just as the Vammika Sutta advises us to ‘leave the dragon’, in the Gundungurra story, the diver-bird fails to dislodge the monster. He contents himself with gouging off a piece of the serpent’s meat. This they consume, taking the serpent’s body into their own, becoming one in flesh. Mirragan, for all his destructive obsession with slaying the beast, is content with just this much.

Perhaps the most powerful thing we have to offer is renunciation. The joy of simplicity and contentment. The knowledge, learned from our own experience that with a simple life comes clarity and ease.

Enough, as Mirragan eventually came to learn, is enough.

Mirrigan pursued his goal, ferociously and relentlessly. But he was content to eat just a piece of flesh, leaving the great serpent-spirit alive and safe in the depths. That is why they both survived, a living presence in the landscape to this very day. We have shown no such restraint, no such wisdom. We kill the serpent, poison his waters and wipe out his forests.Courage on the Spiritual Path

I didn’t come here to bring you hope. It’s too late for that. We don’t need hope; what we need is courage. Stay close to each other, support each other, live simply in the real world, and listen to the truth whispered to you in the trees. Never be afraid to step forward and show leadership to share your wisdom and compassion.

The great spiritual traditions, including Buddhism, acknowledge that despair can be a spur to deep introspection and transformation. Think of the crisis that Siddhattha went through when he faced up to the reality of universal death and suffering. There is a way out, but we will not find it through denial or mollycoddling. Our Teacher has taught us that all things are impermanent, that we should not hide from change, but should live each day in awareness and compassion.

As spiritual practitioners, it is up to us to show honesty and realism, to set an example of how it is possible to live in the face of radical change. Impermanence is core to our philosophy: are you ready to live it? This world, this beautiful fragile world, needs you more than you know.

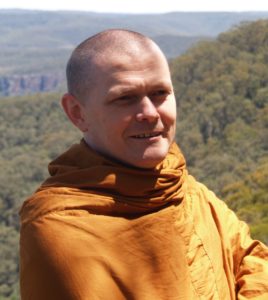

OLYMPUS DIGITAL CAMERA

Bhikkhu Sujato

Bhante Sujato is an Australian Buddhist monk who ordained in 1994 in Thailand. He was instrumental in supporting the revival of the Bhikkhuni order in the Forest Tradition. He has written several books and in 2016/2017 he translated the entire text of the four Pali Nikayas into English. He is the leader of Sutta Central, which gathers together early Buddhist suttas in both original languages and translations in 40 modern languages. He currently lives at Lokanta Vihara, ‘The Monastery at the End of the World’ in Harris Park near Parramatta, the lands of its traditional owners, the Burramattagal people of the Darug nation. At Lokanta Vihara, its community explores what it means to follow the Buddha’s teachings in an era of climate change, globalised consumerism, and political turmoil.

![Call of the Dakini | A Memoir of a Life Lived [Extract]](https://regenesis.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Catalogue-OF-Articles-by-Barbara-Lepani-July-2018-July-2023-.jpg)

Recent Comments