Lorraine:

Well, as we move into a less restricted life we can also look forward to bookshops and libraries opening up and the joy of new books. My own bookshelves have been perused over and over. However, revisiting and rereading old books can renew forgotten aspirations, offer inspiration and hope at a time when it is in short supply. Many of us have used the time at home to think about what sort of world we want as we hopefully put this pandemic behind us.

Must we look forward to the old ‘jobs and growth’ mantra or can we imagine and remake our future starting from a quite different place? Just now the focus of that different place is on black lives and how they matter.

There are few causes more worthy and I would love to provide some appropriate quotes but my reading over the last couple of months has largely consisted of nature writing.

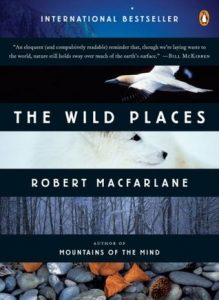

I had ordered Robert Macfarlane’s new book but the post has been so slow that I am still waiting for it to arrive. So I returned to his first book The Wild Places. Although set in the UK and Ireland the sentiments expressed are equally important here and with so much happening in the world it is easy to lose sight of the important role nature writing plays in the world; how it brings us back to our basic connection to the non-human world. So for this month here are a few of Macfarlane’s thoughts.Macfarlane, Week 1:

‘The basic definition of wildness has remained constant … but the values ascribed to this quality have diverged dramatically. On the one hand, wildness has been perceived as a dangerous force that confounds the order-bringing pursuits of human culture and agriculture. Wildness, according to this theory, is cognate with wastefulness. Wild places resist conversion to human use, and they must therefore be destroyed or overcome. …

‘The basic definition of wildness has remained constant … but the values ascribed to this quality have diverged dramatically. On the one hand, wildness has been perceived as a dangerous force that confounds the order-bringing pursuits of human culture and agriculture. Wildness, according to this theory, is cognate with wastefulness. Wild places resist conversion to human use, and they must therefore be destroyed or overcome. …

Parallel to this hatred of the wild, however, has run an alternative history: one that tells of wildness as an energy both exemplary and exquisite, and of wild places as realms of miracle, diversity and abundance’ (pp.30-31).Macfarlane, Week 2:

‘Woods and forests have been essential to the imagination of these islands, and of countries throughout the world, for centuries. It is for this reason that when woods are felled, when they are suppressed by tarmac and concrete and asphalt, it is not only unique species and habitats that disappear, but also unique memories, unique forms of thought. Woods, like other wild places, can kindle new ways of being or cognition in people, can urge their minds differently’ (pp. 98-99).Macfarlane, Week 3:

‘Thought, like memory, inhabits external things as much as the inner regions of the human brain. When the physical correspondents of thought disappear, then thought, or its possibility, is also lost. When woods and trees are destroyed – incidentally, deliberately – imagination and memory go with them. W. H. Auden knew this. “A culture,” he wrote warningly in 1953, “is no better than its woods”’ (p. 100).Macfarlane, Week 4:

‘Wild animals, like wild places, are invaluable to us precisely because they are not like us. They are uncompromisingly different. The paths they follow, the impulses that guide them, are of other orders. The seal’s holding gaze, before it flukes to push another tunnel through the sea, the hare’s run, the hawks’ high gyres: such things are wild. Seeing them, you are made briefly aware of a world at work around and beside our own, a world operating in patterns and purposes that you do not share. These are creatures, you realise, that live by voices inaudible to you’ (p. 307).

![Call of the Dakini | A Memoir of a Life Lived [Extract]](https://regenesis.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Catalogue-OF-Articles-by-Barbara-Lepani-July-2018-July-2023-.jpg)

Recent Comments