David Pledger—Thinker and Provocateur

David Pledger—Thinker and Provocateur

The following ideas in this blog post are taken from the writings of David Pledger an award-winning contemporary artist, curator, cultural commentator and thinker working within and between the performing, visual and media arts. David writes regularly for Daily Review.

David is a graduate of the National Institute of Dramatic Arts (NIDA, Acting). He holds a BA (Politics, Cinema) and an MA (Asian Studies) from Monash University, Melbourne. In 2017, he completed a PhD in the Spatial Information Architecture Lab (SIAL), School of Architecture and Design, RMIT University, Melbourne. Wall of Noise, Web of Silence investigates the effect of ‘noise’ on our social, cultural, corporeal and political systems and is published online in the form of a concept album.

He makes digital art, television documentaries, live performances, site-specific festivals, locative installations, discursive events and interactive artworks for broadcasters, theatres, galleries, arts centres, museums and public sites in Australia, Asia and Europe. His practice interests include the body, the politics of power, the digital realm and public space. He is founding Artistic Director of not yet it’s difficult (NYID), one of Australia’s seminal interdisciplinary arts companies.Thoughts on Our Current Crises

We require a massive overhaul of the arts and culture sector to help deal with the existential, climate crisis our country faces. The current system that governs the daily conditions of artists’ lives is broken.

In the language of pathology that dominates our world, our current reality is that the arts sector’s immune system is severely compromised and has been under significant stress for over a decade. Unless something is done quickly, as in now, the sector will enter palliative care. First, artists, then the rest will follow.

The Covid-19 Pandemic has not caused this.

It’s simply brought into sharp relief the working reality of the Australian artist, a consequence of the interweaving of colonialism, capitalism and patriarchy into the fabric of mainstream political and economic culture, and ultimately, civil society. It’s the Holy Trinity of neo-liberal power that divides, disturbs and alienates, and has an abiding distaste for the plurality of ideas, feelings and senses that generate and receive the arts.Current Power Structures—Aborescent Forms of Leadership

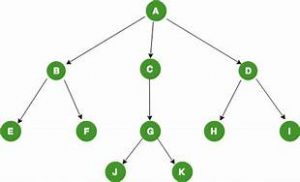

Aborescent leadership is hierarchical, based on a tree-like conception of knowledge, which works with dualist categories and binary choices. An arborescent model works with vertical and linear connections. It is the dominant knowledge system of the globalised modern world. In Australia, it has taken the form of neo-libealism.

Neo-liberal power structures may be read vertically, top-down silos with clear values, hierarchies and control flows. The vertical tends to ensconce power at the top, creating elites, perceived and actual.

A variation can occur when we flip the vertical ninety degrees to the horizontal. We flatten the hierarchy but the flows of control remain. If we go one step further and create a structure that’s horizontally conceived and vertically integrated, then we make a matrix with multiple, intersecting points of power, but it’s still governed by the values of the old system. And they centre around profit.

My reading of Australia’s major cultural entities is that they operate in the interplay of these two axes: the vertical and the horizontal. Bled through these axes is the powerful virus of managerialism, that warps the structure so that no other form of thinking or action is possible. Endgame.Alternatives—Rhyzomatic Forms of Leadership

Reference: Gilles Deleuze & Felix Guattairi, A Thousand Plateaus,1987

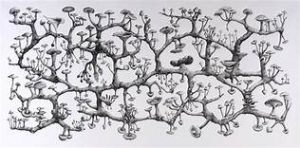

In the arts space, I’ve been talking quietly about rhizomatic forms of leadership and organisational design. A rhizome is basically a plant stem that sends out shoots and nodes – things heading somewhere, and points for those things to go through. A rhizome works with planar and trans-species connections. The planar movement of the rhizome resists chronology and organization, instead favouring a nomadic system of growth and propagation.

Rhizomatic systems are worth a look because they consolidate growth horizontally whilst also having the capacity to shoot upwards. So, their behaviour is kind of familiar. There are some good examples already in the arts around collective artistic directorates and operational models in project contexts. The Tasmania-based Big hART are quite good at the latter.

As a model for culture, the rhizome resists the organizational structure of the root-tree system which charts causality along chronological lines and looks for the original source of ‘things’ and looks towards the pinnacle or conclusion of those ‘things.’ A rhizome, on the other hand, is characterized by ‘ceaselessly established connections between semiotic chains, organizations of power, and circumstances relative to the arts, sciences, and social struggles.

In this model, culture spreads like the surface of a body of water, spreading towards available spaces or trickling downwards towards new spaces through fissures and gaps, eroding what is in its way. The surface can be interrupted and moved, but these disturbances leave no trace, as the water is charged with pressure and potential to always seek its equilibrium, and thereby establish smooth space

What I like about the rhizomatic model is its nod to the natural world and its reflection of our ways of being in that world. It’s also very practical. At this critical juncture, it actually describes what is happening in terms of organising, mobilising and activating civil society. It also reflects best the medium we use to do a lot of that, the Internet. It’s a bit messy, it’s relational, it’s very human(e), it grows in a way that is tentacular.

Rhizomatic forms of leadership are absolutely key to sharing power, which in our political system means sustaining democracy. Which is good. We don’t have to invent a new system. We just amplify some of its existing, minor chords.Responding to the Challenges

When thinking about how the arts might respond to the challenges of climate change and pandemics we might consider the following:

- Need to engage in deep and serious commissioning relationships with artists to help materialise their ideas.

- Programming needs to shift towards art made for and about the severe changes our climate – and by extension, our society – is experiencing.

- Beautiful works to inspire the imagination to help us dream up new ways of being, acting and behaving.

- Controversial offerings that tell of the realities we might face and ways we might change our behaviour in order to mitigate and cope with this future.

- Considered examinations of our relationship with the land, the landscape, the environment.

- Courage is not a word often associated with leaders of our major cultural institutions but if they don’t find it now then they need to leave.

We need to build alliances with other sectors, bring our issues to tables outside the arts, prosecute the idea that what is happening within the arts is happening outside the arts. We need to build a coalition of cross-sectoral interests that includes the arts. This is a long-term contextual strategy.

David Pledger, 2020

![Call of the Dakini | A Memoir of a Life Lived [Extract]](https://regenesis.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Catalogue-OF-Articles-by-Barbara-Lepani-July-2018-July-2023-.jpg)

Recent Comments