Baird is well known to many of us as the host of the ABC’s talk show, The Drum. However, she is also an historian and writer, author of Victoria, a biography of Queen Victoria, which critics have hailed as a triumph.

Baird is well known to many of us as the host of the ABC’s talk show, The Drum. However, she is also an historian and writer, author of Victoria, a biography of Queen Victoria, which critics have hailed as a triumph.

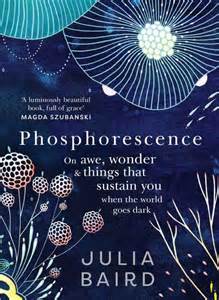

In her recently published, Phosphorescence, Baird takes us on a journey that is acutely personal, but which also draws on authoritative research as she structures the story line.

Inner Luminosity

Julia Baird’s book promises to be about ‘awe, wonder and the things that sustain you when the world goes dark’. Baird links the natural display of phosphorescence in sea creatures and nature, due to bioluminescence, to the idea of the ‘inner light’ of people who seem to glow with joy and alivedness. This is something long associated with the spiritual life across numerous traditions from organised religion to forest shamans, and experienced in individuals sufficiently in touch with the strength of their inner spirit and its connectedness to the world around them. To ‘sustain us when the world turns dark’, Baird draws on her own experiences of personal heartache, which we presume was from a relationship breakdown, and then her sustained battle with breast cancer.

What has fascinated and sustained me over these last few years has been the notion that we have the ability to find, nurture and carry our own inner, living light to ward off the darkness. This is not about burning brightly but yielding simple phosphorescence—being luminous at temperatures below incandescence, quietly glowing without combusting (p.12).

The Ocean

She describes with vivid detail how her membership of the ‘Bold and Beautiful’ Manly ocean swim group has both healed her physically and introduced her to a world of underwater wonder and a deep spiritual connection with the wild forces of the ocean. Baird draws on research to show we, along with all creatures, were born of the sea, and it continues inside us, quoting her neighbour, philosopher Peter Godrey Smith:

She describes with vivid detail how her membership of the ‘Bold and Beautiful’ Manly ocean swim group has both healed her physically and introduced her to a world of underwater wonder and a deep spiritual connection with the wild forces of the ocean. Baird draws on research to show we, along with all creatures, were born of the sea, and it continues inside us, quoting her neighbour, philosopher Peter Godrey Smith:

All the early stages [of life] took place in water: the origin of life; the birth of animals, the evolution of nervous systems and brains, and the appearance of the complex bodies that makes brains worth having… When animals did crawl onto dry land, they took the sea with them. All the basic activities of life occur in water-filled cells bounded by membranes, tiny containers whose insides are remnants of the sea

For Baird, who has spent much of her life as a journalist and media commentator in the public eye, ocean swimming has given her the experience of the power of feeling small against the larger world of nature—to experience the awe that comes from being silenced by something greater than ourselves, something unfathomable, unconquerable and mysterious (p.30). She talks movingly about the power of connections among her fellow swimmers who age from the young to the very old.

We are a strong community, a motley crew bound by a common love [enjoying] the conversations of our diverse crowd—which includes judges, carpenters, models, priests, doctors, care workers and teachers… In an era of increasing disconnection, digital-only relationships and polarisation of political views, it is wonderful to sit among such a varied group of people… as we complain about how long it takes for the local café to make our hot drinks (p.26).

We are a strong community, a motley crew bound by a common love [enjoying] the conversations of our diverse crowd—which includes judges, carpenters, models, priests, doctors, care workers and teachers… In an era of increasing disconnection, digital-only relationships and polarisation of political views, it is wonderful to sit among such a varied group of people… as we complain about how long it takes for the local café to make our hot drinks (p.26).

Connecting with Country

As befitting any thoughtful Australian, Julie Baird reveals how this sense of spiritual connection to the ocean is a reflection of the culture of Australia’s First Nation’s people, which calls on them to ‘care for Country’ and instils in them the way of listening to their Country, to the presence of the Ancestral Beings and their totem spirits, active in the landscape since time immemorial. It is why Aboriginal figures like Joe Williams, author of The Enemy Within, talk about healing people’s broken spirits by taken them ‘on country’.

As befitting any thoughtful Australian, Julie Baird reveals how this sense of spiritual connection to the ocean is a reflection of the culture of Australia’s First Nation’s people, which calls on them to ‘care for Country’ and instils in them the way of listening to their Country, to the presence of the Ancestral Beings and their totem spirits, active in the landscape since time immemorial. It is why Aboriginal figures like Joe Williams, author of The Enemy Within, talk about healing people’s broken spirits by taken them ‘on country’.

Baird links this ancient knowledge to the growing international interest in the ancient Japanese Buddhist and Shinto inspired art of shrin-yoku, forest healing, discussed at length in Dr Qing Li’s book, Shrinrin-yoku: The Art and Science of Forest Bathing. In an interview with Baird, Qing Li said people suffering ‘nature deficit disorder’ regularly come to him seeking a cure for a problem they have no name for: a general unease, anxiety or sadness. Nature bathing enables people to recover the skills of effortless attention, soft fascination and absorption.

This surge of interest in forest bathing, and connection to the natural world is driven by our alienation from nature due to rapidly increasing rates of urbanisation consigning many of us to living in high rise apartments, commuting to work in crowded trains and buses or alone in our cars on clogged freeways, and then many hours in air conditioned offices with artificial light. Baird quotes the author Florence Williams, The Nature Fix: Why Nature Makes Us Happier, Healthier and More Creative, who suggests that we’re experiencing a mass generational amnesia enabled by urbanisation and digital creep, and links this to evidence of increasing loneliness among the crowding and the rising tide of anger in road rage and social media trolling. The power of Aboriginal connection to country was brought home to Baird when she visited the Garma Festival in 2018, held on Yolngu Land in the Northern Territory. Here the elders introduced her to the art of just sitting still and listening, instead of trying to grab hold of things and capture them, in the way of the modern journalist. She recalls witnessing a dawn sacred women’s crying ceremony where the senior women present cried for their land, and their people, mourned, and comforted and called to each other.

The power of Aboriginal connection to country was brought home to Baird when she visited the Garma Festival in 2018, held on Yolngu Land in the Northern Territory. Here the elders introduced her to the art of just sitting still and listening, instead of trying to grab hold of things and capture them, in the way of the modern journalist. She recalls witnessing a dawn sacred women’s crying ceremony where the senior women present cried for their land, and their people, mourned, and comforted and called to each other.

We sat in silence, ringed by smouldering fires and eucalypts on a ridge with views of the far-off sea, transfixed. It was suffering and solace in song, a lament of love, a raw paean of life. It was unlike anything I have ever heard. At the end, the women paused and one elder said: ‘And now we wait for the bird to sing.’ One minute later, it did (p.72).As Palyku woman Ambelin Kwaymullina said to Baird:

Country is more than just a place. Rock, tree, river, hill, animal, human—all were formed of the same substance by the Ancestors who continue to live in land, water and sky… Country is family, culture, identity. Country is self… In the learning borne of country is the light that nourishes the world (p.49).

The Power of Silence

Long recognised in all spiritual traditions, periods of silence allow for us to become free of our habitual distractions, and to settle into ourselves, to learn how to just ‘be’. In this space we can become aware of ‘the presence of life, interwoven’ (p.68). The Christian Indigenous elder, Miriam Rose Ungunmerr-Bauman has highlighted the power of this for Aboriginal people in the idea of dadirri, inner deep listening and quiet still awareness.

Long recognised in all spiritual traditions, periods of silence allow for us to become free of our habitual distractions, and to settle into ourselves, to learn how to just ‘be’. In this space we can become aware of ‘the presence of life, interwoven’ (p.68). The Christian Indigenous elder, Miriam Rose Ungunmerr-Bauman has highlighted the power of this for Aboriginal people in the idea of dadirri, inner deep listening and quiet still awareness.

My people are not threatened by silence. They are completely at home in it. They have lived for thousands of years with Nature’s quietness. My people today recognise and experience in this quietness the great Life-giving Spirit, the Father of us all… Our Aboriginal culture has taught us to be still and to wait. We do not try to hurry things up. We let them follow their natural course—like the seasons… To be still brings peace—and it brings understanding… We are asking our fellow Australians to take time to know us, to be still and to listen to us… (p.73-74)

Perhaps in this age of forced hibernation due to the Coronavirus pandemic, despite our temptation to immerse ourselves in the digital world of the 24 hour news cycle and tsunami of information about how we should live our lives transformed by social distancing and unemployment, we will also begin to discover the power of quiet time. This will be hard for many of us, trapped with small children in apartments and crowded housing, fretting with anxiety about health and income. But without recovering some sense of the power of silence, we could easily lose ‘our minds’ in an avalanche of anxiety and depression. It is time for shopping therapy and striving workforce ambition to be replaced by something else that nurtures our inner spirit.

Baird’s book, Phosphorescence points some of the ways we might do this. In particular we must learn how to escape one of the most dangerous viruses of our time—the misuse of social media that is increasing destructive narcissism through invidious comparison of our imperfect self images and lives with the doctored images of others and their perfect lives, to become vulnerable victims of cyber bullying and cyber trolls, to fall for cruel scams to take our scarce resources with false promises (p.87).

Later in her book, Baird draws inspiration from the Catholic mystic and Buddhist practitioner, Thomas Merton, who lived as a Trappist monk at Gethsemani Abbey in Kentuncky in the 1940s.

Later in her book, Baird draws inspiration from the Catholic mystic and Buddhist practitioner, Thomas Merton, who lived as a Trappist monk at Gethsemani Abbey in Kentuncky in the 1940s.

God talks in the trees. There is wind, so that it is cool to sit outside. This morning at four o’clock in the clean dawn sky there were some special clouds in the west over the woods, with a very perfect and delicate pink, against deep blue. A hawk was wheeling over the trees. Every minute life beings over again. Amen (p.242).

Activism

Julie Baird is also a committed and practising Christian who has fought a long battle with the hardline conservatives of the Sydney Anglican Diocese about the role of women in the Anglican Church. An outlier in the Anglican community, the Sydney Diocese adheres to the ‘quaint’ doctrine of male headship, and a reading of the bible that asserts God only allows men to perform his sacred sacraments. Baird’s struggle with the patriarchal institutional structures of many religious faiths saw her also investigate the extent of domestic violence among the religious, hidden behind of the idea of male headship, following witnessing a 1992 courtcase in which a row of male judges faced a row of men in wigs, as a small crowd of women watched from chairs provided for the public.

A group of men from the church were appealing to a group of men of the law to stop women from entering higher ranks. To stop women from speaking for God. To stop women seeking equality. To stop women. Something about that smelled bad (p.95).

After the rest of the church, and much of the rest of the world, decided to allow women to be priests in 1992, the men of Sydney started refusing to allow women in pulpits at all: indeed the widely touted rule is now that a woman should not speak if any male past puberty is present. The doctrine of headship (p.99).

Despite the failure of Baird’s efforts to change the minds of her Anglican Church in Sydney, Baird draws strength from the history of activism. Nothing was ever easy. For one step forward, there are many backwards—the abolition of slavery, the Suffragettes effort to get women the vote, the trade union movement’s efforts on behalf of working men and women, the long history of struggle by Indigenous Australians for social, cultural and economic justice still playing out, and the more recent struggle of climate scientists and environmentalists to save the Earth from a far bigger and more long term calamity than the coronavirus pandemic.

Such efforts—when people work for justice or simply to improve the lives of other people, and try to ensure the voiceless are heard and the marginalised are pulled into the centre, but get nowhere, for a very long time—are not failure but examples of striving without instant reward.. Walls don’t fall at the blast of a single trumpet, and nor do tyrants, but only after a long, slow symphony that only becomes audible when it reaches a crescendo (p.102).

Faith

As well as being a journalist, writer and intellectual, Julie Baird is a woman of Christian faith. For her, like many Christian activists, Christianity is at its most powerful when it is at the margins or periphery not the centre of power, and when it is identified with outsiders, not exclusive clubs, and with action, not finger-wagging. After all, Jesus was the ultimate outsider figure. It is why Christianity has always had a powerful attraction for the marginalised—among the survivors of the American slave trade and its extraordinarily powerful gospel music tradition. This is also true in Australia among many Aboriginal people, who have made Christianity their own sort of religion.

Baird claims to be untroubled by religious dogma, and to be stubbornly cheerful and enduring for:

I love the mystery, the poetry, even the uncertainty of religion. Stage fights between atheists and religious scholars bore me: they’re usually abstract, riddled with clichés and run by men… My faith continues to exist because I have an understanding of humanity as screwed up, of male-led institutions as narrow—blinded by misogyny and sometimes very dangerous for the vulnerable—and a sense of God as large, expansive, forgiving, infinite and both incomprehensible and intimate (p.249)

Faith is raiding the unspeakable. Grace is forgiving the undeserving. It’s a kind of unfathomable magic. And despite everything, if you can somehow try to let your life be your witness to whatever it is you believe, grace will always leak through the cracks (p.259).

Final Thoughts

After taking her readers on the journey of her own life, leading to reflections on related research and the writings of others, Julie Baird draws her book to a final musing on how do we continue to glow when the lights turn out? She concludes that it is not by endless inner speculation on our life’s travails with a therapist, but by bearing witness to the world around us in all its glory and troubles. To keep placing one foot in front of the other and to seek out ancient paths of wisdom and the forests, oceans and deserts. To love. To care for others, to seek wonder and awe, to find the magic that will sustain us and fuel the light within—our own phosphorescence.

What is crucial for calm is not just a capacity to empty minds of nonsense but to also fill them with good and marvellous things, with a care for others… There is a reason the great philosophical traditions tell us to cultivate attentiveness to the burdens and struggles of people who live alongside us… What if we can fight distraction not by emptying our minds but by focusing them, so that the mind becomes mind-full, and we find focus, absorption, immersion in something other than ourselves (p.276)?

![Call of the Dakini | A Memoir of a Life Lived [Extract]](https://regenesis.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Catalogue-OF-Articles-by-Barbara-Lepani-July-2018-July-2023-.jpg)

Recent Comments