The poet/gardener Alice Oswald writes: “I don’t know anything lovelier than those free shocks of sound happening against the backsound of your heart … spadescrapes, birdsong, gravel, rain on polythene, macks moving, … seeds kept in paper, potatoes coming out of boxes, high small leaves or large head-height leaves being shaken, frost on grass … also when you look up, … the landscape as a physical score, … – weather, daylight, woods, all long unstable rhythms and dissonance. When I’m writing a poem, the first thing I hear is its shape somewhere among all that noise” (Oswald, 2000, p. 35).Garden noise for Oswald is a catalyst for creating a poem and it is the way she evokes a garden saturated by sound that specifically interests me. Listening while working in the garden, Oswald says, is a way of opening a poem out to what lies bodily beyond it. While the eye takes in surfaces, the ear tells us about volume and depth – like tapping a water tank to find how full it is. Listening in such a way, she says, creates poetry in which language is open, porous, allowing what we don’t know to pass through it. It opens a space within human language that reveals the mystery of otherness.

An ecopoetic practice such as Oswald’s disrupts the purity of human speech, and returns it to an enlivened wholeness. For example, she claims that the sound and motion of raking garden leaves puts humans in close contact with otherness. A rake is “a rhythmical but predictable instrument that connects earth to our hands.” Through this kind of close contact you can, she writes, “ hear right into the non-human world, it’s as if you and the trees had found a meeting point in the sound of the rake” (Oswald, 2005, p. xi).Oswald is unusual in that the sounds she mentions are a combination of noises created by human activity along with the sound of wind, rain, leaves and birds. It is this mix of ambient sounds that are a major influence on her thought and poetry writing.

Traditionally gardens have been associated with visual pleasure but after reading Oswald I have been experimenting with combining sight and sounds to open up a space that allows us to apprehend otherness, that puts our minds into imaginative flight beyond the confines of the garden and lets us sense the depth and breadth of life beyond the human.

Like Oswald, I think of a garden not simply as a humanly cultivated space, but as a layered field of poetics involving “groundwork,” it is a place to think about thinking; to enact and embody our physical relationship with the world. It is also a soundscape within which poetry can either be created or encountered in written form, offering us a route to explore multiple layers of otherness and stimulate us to respond sensitively to nature in general. Variations on this tradition have been revived in some twenty-first century gardens such as Little Sparta in Scotland, created by the poet/gardener Ian Hamilton Finlay. Finlay was particularly attracted to inscriptions, a traditional aspect of gardens – the words on sundials are an obvious example. Part of the appeal of inscriptions has always been that they were a means of bringing the outside world into the garden through the simple expedient of alluding to it.

Variations on this tradition have been revived in some twenty-first century gardens such as Little Sparta in Scotland, created by the poet/gardener Ian Hamilton Finlay. Finlay was particularly attracted to inscriptions, a traditional aspect of gardens – the words on sundials are an obvious example. Part of the appeal of inscriptions has always been that they were a means of bringing the outside world into the garden through the simple expedient of alluding to it.

Fragments in a Finlay garden – quotations out of context, solitary words, are like icebergs, just the tips of a world that we cannot see but must assume to be there, fractions of a larger and mysterious world under the surface.

For example, Finlay’s many ‘WAVES’ in whatever language function in this way, as scraps of a larger ocean, as tokens of the sea that is absent yet almost obsessively remembered and associated for Finlay with the sacred.My interest in using ecopoetry although similar has a somewhat different emphasis. Ecopoems can be defined as “provide[ing] models of altered perception that promote environmental awareness and active agency” (Scigaj, in Lynch & Naramore Maher, 2012, p.128). They “signal a conscious re-engagement with a world that is familiar and strange, full of animals and plants that we must answer to, and which we need to address again, more carefully, to define the questions that will help us to renegotiate ways of living in an uncertain future of biodiversity loss, climate change and the consequences of disposability” (Borthwick, 2012, p. xvi).

Ecopoetry in a garden is not necessarily didactic like the eighteenth century emblematic garden but provides visual fragments as imaginative stimulation, an entry into the depth of otherness that Oswald writes of.

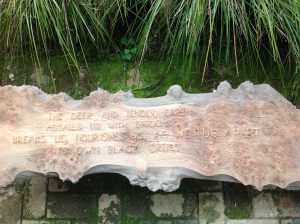

Wandering through a garden, working in a garden, aware of sound, and encountering a poem creates a pause, a moment of thought in which we become aware of the sounds and rhythms of the poetic fragment placed within the background of garden sounds.This search for an ecopoetics in which garden others break through and alter our consciousness closely resembles poet Martin Harrison’s comment, “That we must listen to what is other than human and how it is speaking to us and that the act of attention between self and the environment is intertwined and interdependent and completely mutual” (Harrison, 2013, p. 11). The following few photographs illustrate some initial experiments in creating eco-poetic emblems in my garden. My aim in choosing poetry and including it in a concrete form in the garden has been to articulate and constantly re-experience ecological issues and deepen my apprehension of the mystery of otherness. Working in the garden I find myself implicated in the ground’s world, thought and earth passing through each other. For visitors walking through the garden these poetic fragments hopefully stimulate thoughts of “a way of being toward the world and toward the self that are not separable” (Elvery, 2013, np)

The following few photographs illustrate some initial experiments in creating eco-poetic emblems in my garden. My aim in choosing poetry and including it in a concrete form in the garden has been to articulate and constantly re-experience ecological issues and deepen my apprehension of the mystery of otherness. Working in the garden I find myself implicated in the ground’s world, thought and earth passing through each other. For visitors walking through the garden these poetic fragments hopefully stimulate thoughts of “a way of being toward the world and toward the self that are not separable” (Elvery, 2013, np)

The first is a fragment from Hugh MacDiarmid’s poem “On a Raised Beach.”

We must reconcile ourselves to the stones

Not the stones to us.

We are immediately faced with a sense of geological time, of how short human existence has been on this planet in comparison to great rock formations or even the humblest pebble and of how, as he writes, “what happens to us is irrelevant to the world’s geology. But what happens to the world’s geology is not irrelevant to us.” Inevitably I find it leads me to consider how I continue to see myself as a self-contained subject imagining I control the garden.

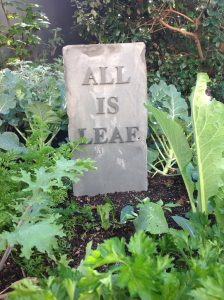

For me, therefore, this fragment of MacDiarmid’s poem placed in the garden articulates the fundamental problem of ecological thought: that of fallaciously thinking we exist outside the world of nature. Yet it also draws attention to how language can set us outside nature. In its entirety “On a Raised Beach” highlights the essential paradox of ecopoetics: that language is both a barrier and a conduit to our experience of the natural world. It asks what poetry is actually capable of representing – in a way defining the limits of ecopoetics. As a contrast, the quote from Goethe, “All is Leaf” moves us into the realm of animate things. Like McDiarmid, Goethe is dealing with large-scale ideas, of becoming aware of form – his leaf is an idea that is realized in all manifestations of a plant: seed, foliage and flowers are all different forms of the ‘leaf’ idea.

As a contrast, the quote from Goethe, “All is Leaf” moves us into the realm of animate things. Like McDiarmid, Goethe is dealing with large-scale ideas, of becoming aware of form – his leaf is an idea that is realized in all manifestations of a plant: seed, foliage and flowers are all different forms of the ‘leaf’ idea.

The plant is nothing but leaf, so inseparably united with the seed to be, that the one cannot be thought of without the other – leading me to contemplate how humans cannot be thought of outside their origin and end in nature. Moya Cannon’s poem “Eros” brings human love into the equation.

Moya Cannon’s poem “Eros” brings human love into the equation.

Cannon comments that, “Nothing perhaps, causes the everyday to fall away, or transfigures the ordinary, like the encounter with Eros. This, one of the most earthed of all our human experiences, binding like birth and death, … opens us to some sense of limitlessness in ourselves …”(Cannon, 1995, pp.1-3). It evokes our creative and destructive drives and our need for hope, which Emily Dickinson describes as “the thing with feathers.” Her deceptively simple metaphor captures the fragility of our aspirations. For her hope is a soft songbird that “perches in the soul,” a metaphor for the more-than-human within the human. Hope as a songbird is neither tame nor in captivity, but merely perching so if it does fly away, it may return. By having the hope-bird never ask for crumbs and implying that the speaker supplies them out of love, Dickinson demonstrates her belief that the tiniest amount freely given can keep hope alive. This exchange of loving generosity between the human and bird provides an antidote to a sense of hopelessness about a world where the more-than-human are invariably deprived of “crumbs.”References:

For her hope is a soft songbird that “perches in the soul,” a metaphor for the more-than-human within the human. Hope as a songbird is neither tame nor in captivity, but merely perching so if it does fly away, it may return. By having the hope-bird never ask for crumbs and implying that the speaker supplies them out of love, Dickinson demonstrates her belief that the tiniest amount freely given can keep hope alive. This exchange of loving generosity between the human and bird provides an antidote to a sense of hopelessness about a world where the more-than-human are invariably deprived of “crumbs.”References:

Borthwick, David. Introduction, Entanglements: New Ecopoetry, edited by David Knowles & Sharon Blackie, Isle of Lewis, Two Ravens Press, 2006.

Cannon, Moya. Editorial, The Poetry Review Ireland, No. 47, Autumn-Winter, 1995, pp.1-3.

Elvery, Ann. Editorial, Plumwood Mountain, Vol. 1, Issue 1013.

Harrison, Martin. The Act of Writing and the Act of Attention, TEXT, Vol. 17, No. 2 (October) 2013.

![Call of the Dakini | A Memoir of a Life Lived [Extract]](https://regenesis.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Catalogue-OF-Articles-by-Barbara-Lepani-July-2018-July-2023-.jpg)

Recent Comments