[vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1536637234884{margin-top: 10% !important;margin-right: 10% !important;margin-bottom: 10% !important;margin-left: 10% !important;padding-top: 7% !important;padding-right: 7% !important;padding-bottom: 7% !important;padding-left: 7% !important;background-color: #ddcdb3 !important;}”]We are learning to see Australia through Aboriginal eyes, beginning to recognise the wisdom contained in their epic story… We cannot imagine that the descendants of people whose genius and resilience maintained a culture here through 50,000 years or more, through cataclysmic changes to the climate and environment, and who then survived two centuries of dispossession and abuse, will be denied their place in the modern Australian nation. We cannot imagine that.

Paul Keating, 1992 Redfern Apology Speech to Aboriginal Australia

My lasting impression from Billy Griffith’s ‘Deep Time Dreaming: Uncovering Ancient Australia’, a beautifully written and moving account of the history of archaeology’s research into Aboriginal culture is twofold. One is to acknowledge that the academic scientific quest and its methods is what enabled non-Aboriginal Australian archaeologists to provide the evidence that Aboriginal people have lived in Australia since the ice age—with a continuous, adaptive culture going back more than 60,000 years. With the new techniques of carbon dating of geological strata and relics, the time for Aboriginal occupation of Australia was push back from 10,000 years to 40,000 years at Lake Mungo to an astonishing 65,000+ years in Kakadu in 2017 through the work of a large multidisciplinary team led by Chris Clarkson, Zenobia Jacobs, Lynley Wallis, Mike Smith, Ben Marwick and Richard Fullagar at Madjedbebe. Meanwhile Paul Tacon of Griffith University reported rock engravings as old as 75,000 years, reported in a feature article in the New York Times. It suggested that these findings were ‘pushing back dramatically the date when humans began to create art’.

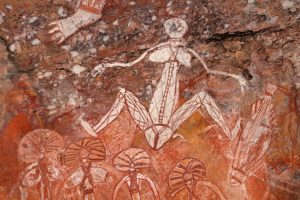

Aboriginal rock art (Namondjok) at Nourlangie, Kakadu National Park, Northern Territory, Australia

The creative arts played a particularly important role in this long history of Aboriginal culture. Art provides a sacred charter to the land, and producing art is one of the conditions of existence. It keeps the past alive and maintains its relevance to the present. Painting, engraving, ritual and ceremony help to focus the power of the Dreaming and re-energise ancestral marks. Researchers slowly began to realise what Aboriginal people have always known, the Aboriginal Dreaming and its Law that dates back to the Ice Age is dynamic, not an unchanging system of meaning, but one continuously responding to events across the ages, as recorded in archaeological sites. As the author Billy Griffith notes, when discussing the find of a female skeleton (Mungo Woman) and later a male (Mungo Man) in the dry salt lakes of Mungo, when the first Australians arrived on the continent some 65,000 years ago, Lake Mungo had been dry for over 50,000 years. As the climate cooled, glaciers formed in the mountains and the melting ice enlarged the rivers. From around 60,000 to 50,000 years ago, the Lachlan River supplied the Willandra Creek with enough water from the snowfields on the Snow Mountains to maintain a system of thirteen lakes with over 200 kilometres of shoreline. A drying trend set in leading up to the Last Glacial Maximum at 23,000 years ago and by around 14,500 years ago the lakes were defunct.The discoveries at Mungo Lake by the geologist, Jim Bowler, and later work by the archaeologist John Mulvaney and his ANU colleagues showed the time-depth and complexity of Aboriginal culture in its use of ceremonial ochre, imported from vast distances, and in the careful arrangement of the body for burial.

As the author Billy Griffith notes, when discussing the find of a female skeleton (Mungo Woman) and later a male (Mungo Man) in the dry salt lakes of Mungo, when the first Australians arrived on the continent some 65,000 years ago, Lake Mungo had been dry for over 50,000 years. As the climate cooled, glaciers formed in the mountains and the melting ice enlarged the rivers. From around 60,000 to 50,000 years ago, the Lachlan River supplied the Willandra Creek with enough water from the snowfields on the Snow Mountains to maintain a system of thirteen lakes with over 200 kilometres of shoreline. A drying trend set in leading up to the Last Glacial Maximum at 23,000 years ago and by around 14,500 years ago the lakes were defunct.The discoveries at Mungo Lake by the geologist, Jim Bowler, and later work by the archaeologist John Mulvaney and his ANU colleagues showed the time-depth and complexity of Aboriginal culture in its use of ceremonial ochre, imported from vast distances, and in the careful arrangement of the body for burial. Yet at the same time, this archaeology also revealed how the scientific worldview of archaeology found it difficult to deal with the implications that the human remains and rock art that they uncovered belonged to a living culture. For this living culture, the human remains were not archaeological artefacts for scientific investigation. Rather than were the bones of their ancestors, with whom, through the Dreaming, Aboriginal people today have visceral connections going right back to the beginning. The rock art, songlines and the ceremonies attached to it were not artefacts for academic discussion, but sacred-secret knowledge that belonged to only those with the correct skin and ceremonial initiation. For the traditional owners of Mungo, Mungo Man recovered from the geological past was not scientific evidence, but one of their relatives, an ancestor, a link to the spirits of their living culture.

Yet at the same time, this archaeology also revealed how the scientific worldview of archaeology found it difficult to deal with the implications that the human remains and rock art that they uncovered belonged to a living culture. For this living culture, the human remains were not archaeological artefacts for scientific investigation. Rather than were the bones of their ancestors, with whom, through the Dreaming, Aboriginal people today have visceral connections going right back to the beginning. The rock art, songlines and the ceremonies attached to it were not artefacts for academic discussion, but sacred-secret knowledge that belonged to only those with the correct skin and ceremonial initiation. For the traditional owners of Mungo, Mungo Man recovered from the geological past was not scientific evidence, but one of their relatives, an ancestor, a link to the spirits of their living culture. As a result of negotiations between the traditional owners of Mungo and the scholar-scientists of the ANU, in 1978 Mungo National Park was created and in 1981 Willandra Lakes became a UNESCO World Heritage landscape. In the generosity of spirit shown so often by Aboriginal people, when Mungo Lady was handed back to a “Keeping Place’ on the site, an Elder, Alice Kelly, said this as not only important for her own culture, but for all Australians, black and white, to embrace us all in its spirituality and draw us closer to the land. Thus Lake Mungo has become a site of symbolic reconciliation between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Australians—but a reconciliation that many of our political leaders are yet to fully embrace.[vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1536638685787{margin-top: 10% !important;margin-right: 10% !important;margin-bottom: 10% !important;margin-left: 10% !important;padding-top: 7% !important;padding-right: 7% !important;padding-bottom: 7% !important;padding-left: 7% !important;background-color: #ddcfaf !important;}”]This same sentiment informs comments from Yolngu man, Galarrwuy Yuninpingu, the 1978 Australian of the Year,

As a result of negotiations between the traditional owners of Mungo and the scholar-scientists of the ANU, in 1978 Mungo National Park was created and in 1981 Willandra Lakes became a UNESCO World Heritage landscape. In the generosity of spirit shown so often by Aboriginal people, when Mungo Lady was handed back to a “Keeping Place’ on the site, an Elder, Alice Kelly, said this as not only important for her own culture, but for all Australians, black and white, to embrace us all in its spirituality and draw us closer to the land. Thus Lake Mungo has become a site of symbolic reconciliation between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Australians—but a reconciliation that many of our political leaders are yet to fully embrace.[vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1536638685787{margin-top: 10% !important;margin-right: 10% !important;margin-bottom: 10% !important;margin-left: 10% !important;padding-top: 7% !important;padding-right: 7% !important;padding-bottom: 7% !important;padding-left: 7% !important;background-color: #ddcfaf !important;}”]This same sentiment informs comments from Yolngu man, Galarrwuy Yuninpingu, the 1978 Australian of the Year,

Let us be who we are—Aboriginal people in a modern world—and be proud of us. Acknowledge that we have survived the worst that the past had thrown at us and we are here with our songs, our ceremonies, our land, our language and our people—our full identity. What a gift this is that we can give you, if you choose to accept us in a meaningful way. (‘Rom Watangu: The Law of the Land’, Monthly, July 2016)What must be remembered in the history of both archaeology and anthropology is that they are products of a combination of European colonialism and the growing intellectual energy unleashed by the scientific revolution. This saw Western scholars determined to discover everything they could about the worlds being revealed through colonial conquest: Asia, Africa and the Pacific. It was British archaeologists who uncovered the remains of Buddhist culture in India at Bodhgaya, dating back 500 years before the current era—a Buddhist culture that had passed from the memory of Indian culture since dominated by Hinduism and Islam—but one which saw the birth of one of the world’s great religions through the meditative insights of Prince Gautama of the Shakya Clan (Shakyamuni Buddha) during the Mahajanapada era, and his forest teachings recorded in the Pali language. European archaeologists were similarly active in Egypt, Mesopotamia and Crete, while European anthropologists were very active in Africa and Melanesia, documenting the lives of ‘uncivilised’ tribal peoples.As Griffiths notes: as a result of colonial dispossession of Aboriginal people of their lands, the traditional owners of Mungo, the Paakantji, Mutthi Mutthi and Ngyampaa people were forced off their land to live in fringe camps in the surrounding towns and settlements of Balranald, Wentworth, Wilcannia and Mildura. In these camps and missions it was illegal to practise aspects of their traditional culture and they were forbidden to speak their language. Up until 1969, the Aboriginal Welfare Board was still forcibly removing Aboriginal people and their children to reserves and managed stations…Aboriginal people became to be seen as trespassers on their own country, aliens in their own land.What was interesting when listening to Q&A with high school students, held in Canberra on 10 September 2018, was the resounding support amongst all of them, those who identify as Liberal supporters and those who identify as Labor supporters, for truth telling history of Aboriginal culture to be made a compulsory part of the school curriculum in both primary and secondary school years.For the Wild Mountain Collective, what is most significant about the work of the archaeologists and anthropologists in ‘uncovering ancient Australia’ is the growing realisation of the way the natural and supernatural realms in Aboriginal culture were entwined as a single reality. Linking ecological knowledge of the plants and animals and climate change necessary for survival with the activities of the Dreamtime ancestors as figures of constant regenerative spiritual energy meant that the health of country was dependent on people continuing to sing the songs, paint the designs and carry out the dances to keep alive its spiritual energies. And this is why dispossession has had such devastating consequences for Aboriginal people when they are separated from their ancestry, country, and language.

An interesting take on this is the observation that Frank Guirrmanamana and Frank Malkorda made when they visited Canberra in 1974 to see this place where the laws impacting them were being made.

An interesting take on this is the observation that Frank Guirrmanamana and Frank Malkorda made when they visited Canberra in 1974 to see this place where the laws impacting them were being made.

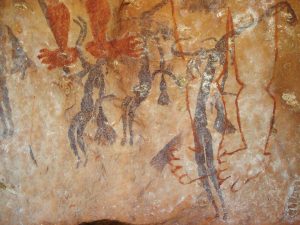

Here was a land empty of religious affiliation; there were no wells, no names of the totemic ancestors, no immutable links between land, people and the rest of the natural and supernatural worlds. Here was a vast tabula rasa, cauterised of meaning… Viewed from this perspective, the Canberra of the geometric streets and the paddocks of the six-wire fences were places not of domesticated order, but rather a wilderness of primordial chaos. For Aboriginal people, art provides a sacred charter to the land, and producing art is one of the conditions of existence. It keeps the past alive and maintains its relevance to the present. Painting, engraving, ritual and ceremony help to focus the power of the Dreaming and reenergise ancestral marks. The archaeologist, Charles Mountford, observed Elders rubbing rock to release their life essence in the course of ceremonies to maintain and increase natural resources. He commented that the ways in which Pintupi men of the Gibson Desert greeted their ancestors was through art – making sensory contact with totemic designs. The old masters who painted and etched the designs found across Australia were not making ‘art’; they were marking country, curating the Dreaming.

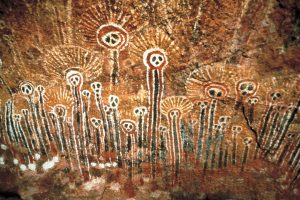

For Aboriginal people, art provides a sacred charter to the land, and producing art is one of the conditions of existence. It keeps the past alive and maintains its relevance to the present. Painting, engraving, ritual and ceremony help to focus the power of the Dreaming and reenergise ancestral marks. The archaeologist, Charles Mountford, observed Elders rubbing rock to release their life essence in the course of ceremonies to maintain and increase natural resources. He commented that the ways in which Pintupi men of the Gibson Desert greeted their ancestors was through art – making sensory contact with totemic designs. The old masters who painted and etched the designs found across Australia were not making ‘art’; they were marking country, curating the Dreaming. This image is from the rock art of the Wollemi National Park. The Blue Mountains World Heritage area is replete with caves with rock art, recorded by Paul Tacon and his Aboriginal archaeologist assistant, Wayne Brennan, who is an expert on Wollemi rock art.

This image is from the rock art of the Wollemi National Park. The Blue Mountains World Heritage area is replete with caves with rock art, recorded by Paul Tacon and his Aboriginal archaeologist assistant, Wayne Brennan, who is an expert on Wollemi rock art.

Wandjuk Marika, co-founder of the Aboriginal Arts Board, urged his fellow Australians to ‘learn more about the stories that our paintings recount, to listen to our songs and music, so that gradually there will grow up between us a bond of understanding and respect, to replace the distrust and fear of previous generations. The development of rock art research alongside the growth of contemporary Aboriginal art movement has allowed a deeper appreciation of the millions of paintings and engravings that mark this country, as well as offering insights into the social worlds of the old masters who created them.The Wild Mountain Collective is dedicated to honouring the 60,000+ year history of Aboriginal culture and its continuous care for country, and to learn from them about how to engage with the creative arts to help keep its spirit alive. We acknowledge the traditional owners of the Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage Area, and pay respects to their elders past and present.

![Call of the Dakini | A Memoir of a Life Lived [Extract]](https://regenesis.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Catalogue-OF-Articles-by-Barbara-Lepani-July-2018-July-2023-.jpg)

Recent Comments