[vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1535251820250{margin-right: 10% !important;margin-left: 10% !important;padding-top: 7% !important;padding-right: 7% !important;padding-bottom: 7% !important;padding-left: 7% !important;background-color: #ddc8a1 !important;}”]

Henryk: As an artist, I do this myself quite a lot. That space between your mind and what is out there—to me this is the most creative space. You need to allow yourself that space and that is where this sculpture came from. It was hellishly difficult to pull off. I started with the head and the chair and then had to connect them. It was 3 months of work. You do a bit, then walk away. I love that. When you get stuck, you take a break, turn the lights off in the workshop, walk away, have a cup of coffee. Walk around and then somehow you know, in an instant, what to do next, because you have fresh eyes. Step back and relax. This is the process.This sculpture is going to a proper place. It will be a church somewhere south of Bathurst, a 1840s church on a farming property. I will have some say, but most likely it will be outside, looking into the distance across the country. I would have hated it, if he was somewhere in a closed space

Henryk: As an artist, I do this myself quite a lot. That space between your mind and what is out there—to me this is the most creative space. You need to allow yourself that space and that is where this sculpture came from. It was hellishly difficult to pull off. I started with the head and the chair and then had to connect them. It was 3 months of work. You do a bit, then walk away. I love that. When you get stuck, you take a break, turn the lights off in the workshop, walk away, have a cup of coffee. Walk around and then somehow you know, in an instant, what to do next, because you have fresh eyes. Step back and relax. This is the process.This sculpture is going to a proper place. It will be a church somewhere south of Bathurst, a 1840s church on a farming property. I will have some say, but most likely it will be outside, looking into the distance across the country. I would have hated it, if he was somewhere in a closed space I am not a conceptual sculptor. One of the sculptors who inspire me is Alberto Giacometti (1901-1966), who was influenced by phenomenology and existentialism. He is best remembered for his figurative work, which helped make the motif of the suffering human figure a popular symbol of post-war trauma. Giacometti is quoted as declaring: “All the art of the past rises up before me, the art of all ages and all civilisations, everything becomes simultaneous, as if space had replaced time. Memories of works of art blend with affective memories, with my work, with my whole life.”

I am not a conceptual sculptor. One of the sculptors who inspire me is Alberto Giacometti (1901-1966), who was influenced by phenomenology and existentialism. He is best remembered for his figurative work, which helped make the motif of the suffering human figure a popular symbol of post-war trauma. Giacometti is quoted as declaring: “All the art of the past rises up before me, the art of all ages and all civilisations, everything becomes simultaneous, as if space had replaced time. Memories of works of art blend with affective memories, with my work, with my whole life.”

The other sculptor who has inspired me is Isamu Noguchi (1904-1988), the Japanese American sculptor and landscape artist, who worked in Paris, making sculpture in stone, wood and sheet metal, spent time in Japan and then returned to the United States. Noguchi is quoted as declaring: “The essence of sculpture is for me the perception of space, the continuum of our existence,” and that he saw sculpture as a vital force in our everyday life, if projected into communal usefulness. Here at Dargan I have my studio where I can work surrounded by wildness.

Here at Dargan I have my studio where I can work surrounded by wildness.

What attracted me to the Wild Mountain Collective is the diversity of people. I don’t want to just meet sculptors or artists alone. I want to also meet writers and musicians, to just exchange ideas. I have been working in a vacuum of criticism for a very long time. Putting myself out there and asking what do you think? I really want people to respond. If it is brutal I can take it. What I want is the interaction.

I am now running Gallery H and that is another business that eats up time. But when I get myself sorted I think I can contribute.

Encountering the Wild in Australia

Encountering the Wild in Australia

I came from Poland to Australia in 1982 as an asylum seeker, wanting to get to a place that was as far away as possible from Poland. I’d been a teacher, an intellectual, but in Australia I found myself working in north Queensland clearing trees in 47 degrees heat—a 60 degree difference from the severe winter temperature of Poland. My fellow workers were mostly outlaws—drug addicts, bikies, ex-Vietnam vets, who all helped me cope, not just with the heat but being immersed in the spiders, snakes, wild dogs and mosquitoes of Australia.

We killed thousands and thousands of trees with poison. I didn’t think about it then, but now living here at Dargan, where I feel so much part of this landscape, which I have come to love for its rugged grandeur, I feel immense sorrow.After leaving Queensland, I travelled around a bit, hitching cars and freight trains before arriving in Sydney where I worked in a foundry. But I was also studying at Sydney University doing a degree in French and there I met my wife, Philippa, who was studying prehistory. Through my wife, who is an artist, I got into art and began making sculptures with casting at the foundry. There I had a good boss who allowed this, and I got access to cheap scrap metal. When that foundry closed, the next one was a terrible place where I found myself breathing in arsenic from stirring the molten metal as there was no exhaust system.

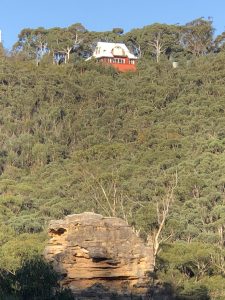

So I quit and began studying art at East Sydney Tech and Philippa and I began a little art business. Soon after our daughter was born, we decided to leave the city, travelling down the south coast and up to the Blue Mountains. Really, without consciously choosing it, we found ourselves liking the mountains and bought a glorious small traditional miner’s cottage with a large garden in Leura. Our neighbour, who was a builder, built us a two-storey brick studio in our backyard and we began our arts-business. This eventually led to us getting a commission to completely fit-out a four-storey restaurant at the Rocks. I did the fit-out. Philippa did the artworks. Then after a while we wanted to leave Leura. It felt too full of people and we needed a bigger studio. We found this place at Dargan and moved here with our two daughters who went to school in Lithgow. This house is surrounded by 10 acres of rugged wilderness that goes all the way down to the creek and up to the top of the ridge on the other side, from which there is a clear view to Hartley. This place is paradise for me.

Then after a while we wanted to leave Leura. It felt too full of people and we needed a bigger studio. We found this place at Dargan and moved here with our two daughters who went to school in Lithgow. This house is surrounded by 10 acres of rugged wilderness that goes all the way down to the creek and up to the top of the ridge on the other side, from which there is a clear view to Hartley. This place is paradise for me.

I find it surreal this concept of ownership of this land. You think, can I really own this? It feels nonsensical. In this way I really came to understand the Aboriginal way of relating to land.

I had this very strong experience one day when walking through a gap between two stone pagodas—15-20 metres tall that are on the other side of the creek. I am not a mystical person, but that day I heard voices. I stopped, feeling a strong sense that there was a subtle barrier. I thought, “Can I move past this?” I remembered the Australian movie, Picnic at Hanging Rock. I saw that in Poland when I was 14 years old. It made a huge impression on me and I saw it again in Australia. Then I gathered myself and thought strongly, “I mean no harm here. I want to protect this place”. And then I was able to move through that space.[vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1535101920139{margin-right: 10% !important;margin-left: 10% !important;padding-top: 7% !important;padding-right: 7% !important;padding-bottom: 7% !important;padding-left: 7% !important;background-color: #ddcdad !important;}”]It felt like a portal through which I passed into a different relationship to the country. It has taken me 15 years, but I have really come to love the rugged, wild quality of the Australian landscape. Everything in Europe feels very aligned. Here it resists all forms of domestication. It remains ‘wild’. Barbara Lepani: I met Henryk when one day I dropped in to Gallery H at Dargan. I instantly fell in love with his sculptures. They felt as if they truly grew out of the rugged landscape of the Blue Mountains with its granite and sandstone cliffs and rocks, wild gorges and sweeping views. All around me were sculptures featuring metal, stone and wood. Here is Henryk’s driftwood piece that really caught my eye.

Barbara Lepani: I met Henryk when one day I dropped in to Gallery H at Dargan. I instantly fell in love with his sculptures. They felt as if they truly grew out of the rugged landscape of the Blue Mountains with its granite and sandstone cliffs and rocks, wild gorges and sweeping views. All around me were sculptures featuring metal, stone and wood. Here is Henryk’s driftwood piece that really caught my eye.

![Call of the Dakini | A Memoir of a Life Lived [Extract]](https://regenesis.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Catalogue-OF-Articles-by-Barbara-Lepani-July-2018-July-2023-.jpg)

Recent Comments